Alcoholic hepatitis

Notes

Overview

Alcoholic hepatitis is a clinical syndrome due to progressive alcohol-mediated liver inflammation and injury.

Alcoholic hepatitis generally refers to the acute onset of symptomatic hepatitis due to heavy alcohol consumption. It can occur at any age, but is more likely in middle-aged patients (e.g. 40-50 years) who have drank excess amounts of alcohol for many years. It is part of a wider spectrum of conditions known as alcohol-related liver disease (discussed below).

Severe alcoholic hepatitis requiring hospital admission is associated with poor short-term survival. However, the true prevalence of alcoholic hepatitis is difficult to ascertain because many mild cases can be asymptomatic.

Typically, alcohol consumption >100 g per day for 15-20 years increases the risk of alcoholic hepatitis. Approximately 8 g of pure ethanol is equal to 1 unit. This refers to approximately 12.5 units per day (87.5 units per week).

This level of consumption would equate to around one bottle of wine, 6 pints of beer, or 250 mls of spirit each day. This depends on the alcohol percentage in each beverage (1000 mls of x% = x units).

ArLD

Alcoholic hepatitis is part of a spectrum of alcohol-related liver diseases due to the excess ingestion of alcohol.

Alcohol-related liver disease (ArLD) refers to a spectrum of conditions that result from alcohol-mediated liver damage. ArLD refers to three conditions:

- Alcoholic fatty liver: metabolism of alcohol leads to deposition of excess fat in the liver. May occur with or without inflammation.

- Alcoholic hepatitis: severe inflammation of the liver. Generally refers to acute symptomatic hepatitis.

- Cirrhosis: irreversible scarring of the liver associated with numerous complications

Patients with ArLD can develop anyone of these conditions. The natural progression is highly variable and the conditions do not reflect a step-wise progression. Alcoholic hepatitis generally refers to the acute onset of symptomatic hepatitis. However, many patients with fatty liver may have underlying asymptomatic steatohepatitis (i.e. inflamed fat within the liver).

Only 1 in 10 patients who drink excess alcohol will develop cirrhosis. Patients with cirrhosis who continue to drink may develop acute on chronic liver failure or acute decompensated cirrhosis due to alcoholic hepatitis. Alternatively, patients with only alcoholic fatty liver may develop alcoholic hepatitis. These patients are at risk of subsequently developing cirrhosis.

Therefore, alcoholic hepatitis is a syndrome due to progressive inflammatory liver injury that may occur in the presence or absence of cirrhosis in the context of continued heavy alcohol consumption.

Epidemiology

Alcohol accounts for the majority of liver disease within the UK.

ArLD is a major public health problem. Rising numbers of people are dying from liver disease associated with alcohol, particularly in young age groups. Mortality from ArLD is estimated at 9.0 per 100,000 people under 75 years old.

It is estimated that 90-100% of patients who chronically abuse alcohol develop alcoholic fatty liver. Continued intake increases the risk of alcoholic steatohepatitis, which could lead to severe alcoholic hepatitis.

The true prevalence of alcoholic hepatitis is difficult to quantify as many milder cases may go unnoticed. Severe alcoholic hepatitis is associated with a high morbidity and mortality. In those who develop severe alcoholic hepatitis and survive, relapse is estimated at 25% after one year.

Aetiology & pathophysiology

Alcoholic hepatitis is due to heavy alcohol consumption over many years (typically >100 g per day).

Alcoholic hepatitis is usually induced by heavy alcohol consumption over years. However, it can develop with a shorter alcohol history and is increasingly seen in younger patients.

Alcohol metabolism

The liver is the primary site of ethanol metabolism. Ethanol and its metabolites are toxic to the liver and can cause hepatocyte injury.

Ethanol is taken to the liver where it is metabolised via different pathways.

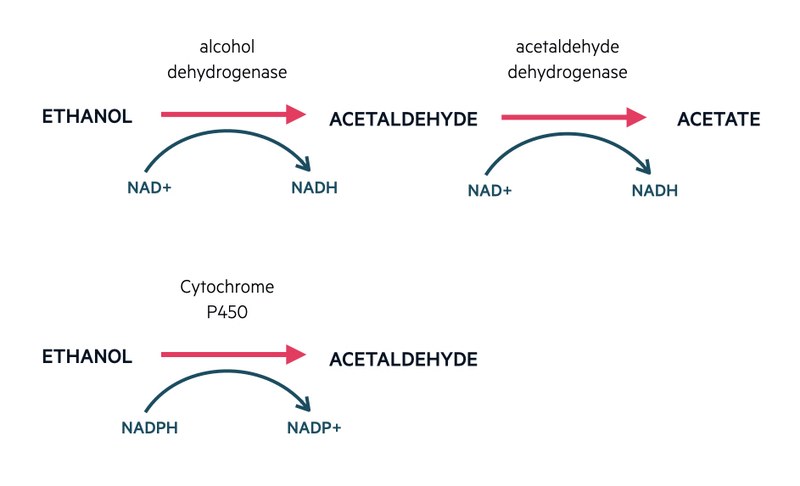

- Oxidative metabolism: Ethanol is converted to acetaldehyde by action of alcohol dehydrogenase. Acetaldehyde is subsequently converted to acetate by the action of acetaldehyde dehydrogenase.

- Microsomal enzyme oxidative system: Ethanol is converted to acetaldehyde by the cytochrome system. Important in the biotransformation of foreign compounds.

NOTE: deficiency or reduced activity of acetaldehyde dehydrogenase can lead to the flushing reaction seen in certain Asian populations when they consume alcohol. This is due to a build up of acetaldehyde.

Liver damage

The development of alcoholic hepatitis is multifactorial related to immunological dysfunction, disruption of the liver-gut axis with alteration in the microbiome (group of microorganisms living within the gut), increased gut permeability with translocation of bacterial endotoxins (e.g. LPS) and direct toxic effects of ethanol metabolism leading to oxidative damage and a pro-inflammatory response.

A marked inflammatory response with neutrophilic infiltration and hepatocyte death is classic of alcoholic hepatitis. This inflammatory response can also lead to the activation of stellate cells, which causes deposition of extracellular matrix proteins, generation of portal hypertension and fibrosis.

Clinical features

Alcoholic hepatitis is characterised by jaundice, anorexia, fever and tender hepatomegaly.

Symptoms

- Jaundice

- Fever: important to rule out infection

- Anorexia

- Abdominal pain

- Abdominal distention (ascites)

- Muscle wasting

- Confusion: seen in encephalopathy and alcohol withdrawal

Signs

- Jaundice

- Tender hepatomegaly

- Ascites

- Asterixis: flapping tremor secondary to encephalopathy

- Tremor: seen in alcohol withdrawal

- Bruising (coagulopathy)

- Stigmata of chronic liver disease: spider naevi, palmar erythema, gynaecomastia, leukonychia

There may be features of underlying chronic liver disease/cirrhosis due to chronic alcohol ingestion. Patients may also present with features of alcohol withdrawal (sweating, tremor, nausea, vomiting, altered mental status, agitation) or have overt signs of encephalopathy (confusion, asterixis, coma).

Diagnosis & investigations

A combination of clinical features and laboratory findings are used to make a diagnosis of alcoholic hepatitis.

Characteristic clinical features and laboratory findings in the context of heavy alcohol consumption is usually enough to make a diagnosis of alcoholic hepatitis. A liver biopsy is usually reserved for severe cases of alcoholic hepatitis. It helps to assess severity, look for underlying cirrhosis and exclude alternative causes of liver disease.

Routine tests

All patients with suspected acute hepatitis, including alcoholic hepatitis, require the following baseline investigations:

- Full blood count

- Urea & electrolytes

- Liver function tests

- Bone profile

- C-reactive protein

- Magnesium

- Coagulation (INR)

- Non-invasive liver screen (see below)

- Liver ultrasound

- +/- septic screen (e.g. blood cultures, urines, ascitic cultures, chest x-ray)

Liver screen

Any patient with acute hepatitis requires a full liver screen including a liver ultrasound with dopplers to assess the architecture of the liver and exclude portal vein thrombosis or Budd-Chiari (i.e. hepatic vein thrombosis).

A liver screen refers to a series of non-invasive investigations to determine possible causes of liver disease (e.g. autoimmune hepatitis, viral hepatitis). In alcoholic hepatitis, it is essential to exclude other causes of acute hepatitis.

For more information, see our notes on chronic liver disease.

Laboratory findings

Acute hepatitis refers to inflammation of the liver of which there are many causes. It is characterised by a transaminitis (rise in liver enzymes) that can be seen on liver function tests.

Laboratory features suggestive of alcoholic hepatitis include:

- Moderately elevated transaminases (< 300 IU/L)

- AST/ALT ratio >2 (other liver diseases rarely cause this ratio)

- Elevated bilirubin (usually > 86 umol/L)

- Elevated gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT)

- Elevated neutrophil count (typically < 20.0 x10^9/L)

- Elevated INR (usually due to impaired synthesis of coagulation factors with severe inflammation)

NOTE: an AST/ALT ratio > 2 is secondary to deficiency of pyridoxal 5'-phosphate in hepatocytes, which is needed as a cofactor for ALT activity. This is low in patients who chronically abuse alcohol.

Liver biopsy

A liver biopsy involves taking a sample of hepatic tissue to assess the underlying architecture. It can be completed percutaneously or transjugular. The latter is usually preferred in patients with deranged clotting, significantly elevated bilirubin or ascites.

A liver biopsy is most likely to be utilised in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis. It can determine the degree of inflammation, assess for underlying cirrhosis and exclude other causes of liver disease. Findings at biopsy may be non-specific, but features can include:

- Steatosis (fat in the liver)

- Neutrophil infiltration

- Hepatocyte ballooning

- Fibrosis

- Cholestasis

- Mallory-Denk bodies: eosinophilic accumulations of proteins within the cytoplasms of hepatocytes. No pathological role in disease but a marker of alcohol-induced liver disease.

Histological scoring systems are available, which are used to determine 90-day mortality.

Alcoholic hepatitis Vs. decompensated liver disease

The clinical and laboratory features of alcoholic hepatitis are similar to decompensated cirrhosis. Decompensated cirrhosis occurs when the liver is unable to carry out its normal function leading to ascites, encephalopathy, jaundice, coagulopathy and GI bleeding. All of these features can also occur in severe alcoholic hepatitis with/without cirrhosis.

Patients with alcoholic hepatitis on a background of cirrhosis are at increased risk of decompensation that will need to be managed concurrently. It is important to recognise alcoholic hepatitis as patients may be eligible to have disease-specific therapy (e.g. corticosteroids) and could be offered to enrol in clinical trials.

Severity

Several models are available to determine the severity of alcoholic hepatitis.

The Maddrey discriminant function (DF), Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) and Glasgow alcoholic hepatitis score (GAH) can all be used to assess the severity of alcoholic hepatitis. These scores are predominantly based on laboratory parameters.

Determining severity of alcoholic hepatitis is important to highlight patients with poor short-term survival and those who would benefit from pharmacological intervention.

Maddrey discriminant function

The DF score has been traditionally use to assess the severity of alcoholic hepatitis. It is based on serum bilirubin and prothrombin time.

DF = (4.6 x [prothrombin time (sec) - control prothrombin time (sec)]) + (serum bilirubin/17.1)

Serum bilirubin (umol/L)

Severe alcoholic hepatitis is defined as a DF score ≥ 32. The 28 day (one month) mortality among patients with a DF ≥32 ranges from 25-45%. Patients with a score < 32 have mild-to-moderate alcoholic hepatitis, which has a <10% mortality at 1-3 months.

Glasgow alcoholic hepatitis score

The GAH is a newer scoring system, which also predicts mortality among patients with alcoholic hepatitis. It is a slightly more complex score based on age, white blood cell count, urea, bilirubin and prothrombin time.

A score ≥ 9 is consistent with severe alcoholic hepatitis and associated with a poor 28-day and 84-day survival (46% and 40%, respectively).

Management

Management is largely supportive with nutritional support, haemodynamic support and treating alcohol withdrawal.

Management principles

Patients with alcoholic hepatitis may have mild disease without complications or severe liver injury. Other patients may have severe alcoholic hepatitis with numerous complications including infection, gastrointestinal bleeding, acute kidney injury, coagulopathy and/or acute on chronic liver failure.

The key principles for all patients with alcoholic hepatitis include:

- Managing alcohol withdrawal: CIWA scoring, benzodiazepines, alcohol team input

- Alcohol cessation: important on discharge and follow-up

- Hydration: cautious fluid resuscitation, especially in patients with acute kidney injury. Consider the use of albumin to reduce the risk of worsening ascites, hyponatraemia and precipitating GI bleeding.

- Nutrition: dietitian input, low threshold for NG feeding and vitamin supplementation (i.e. high dose Pabrinex). The majority of patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis have evidence of malnutrition on admission.

- Aggressive treatment of infections: patients with alcoholic hepatitis are at increased risk of life-threatening infections due to immune dysfunction. Investigations (e.g. blood cultures, chest radiograph, ascites culture) should be completed in any patient with suspected infection. Antifungals may be needed in addition to antibacterials in severe cases.

- Pharmacological therapy: patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis (DF ≥32, GAH ≥9) can be treated with pharmacological therapies including corticosteroids (e.g 40 mg prednisolone for 28 days) or newer agents as part of a clinical trial.

Mild to moderate alcoholic hepatitis

Patients with mild-to-moderate alcoholic hepatitis (DF <32, GAH <9) are usually managed conservatively with good nutrition, attention to adequate hydration and managing alcohol withdrawal.

It is important to screen for underlying chronic liver disease, but the mainstay of treatment is alcohol cessation.

Severe alcoholic hepatitis

Patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis (DF ≥32, GAH ≥9) can be extremely unwell with multi-organ failure and require referral to an intensive care unit (ICU). It is important to manage complications as they arise, which can include infections, GI bleeding, encephalopathy or acute kidney injury. These complications are also seen in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. For more information on the management of these complications see chronic liver disease notes.

Patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis should be considered for corticosteroid therapy. There is limited evidence for the use of steroids in alcoholic hepatitis. In the randomised controlled STOPAH trial there was a trend towards improved short-term survival at 28-days, but no effect on long-term survival. A subsequent meta-analysis including STOPAH showed a survival benefit with steroids at 28-days.

The use of corticosteroids should be guided by hepatologists. They are typically given as a 28-day course of prednisolone at 40 mg daily with a short taper at the end. If there is no significant improvement within 7 days of starting steroids cessation of treatment should be considered because of the risk associated with systemic steroids. The Lille score can be used to identify patients not responding to steroids.

Other treatment options include Pentoxifylline (limited data on benefit) or entry into clinical trials.

Clinical trials

Due to the complex pathological mechanisms involved in alcoholic hepatitis, a number of treatment options are being explored for the treatment of severe cases. Examples include:

- Anti-IL-22: felt to be anti-inflammatory and induce hepatic regeneration

- G-CSF (filgastrim): increases neutrophils and stimulates hepatic regeneration

- IL-1 receptor antagonist (Anakinra)

- Faecal transplant: alters the gut microbiome

Patients presenting with severe alcoholic hepatitis may be eligible to enter into a clinical trial at a tertiary hepatology unit or transplant centre.

Liver transplantation

In the UK, alcoholic hepatitis is not an indication for liver transplantation. In fact, due to the ‘6-month rule’, which means patients need to be abstinent from alcohol for 6 months prior to transplantation, alcoholic hepatitis is a contraindication. Nevertheless, the interest in transplantation for severe alcoholic hepatitis is increasing because of the effectiveness of therapy.

Within selected cases, liver transplantation has been shown to improve survival in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis among studies from Europe and the US. However, it is a contentious area because patients are still drinking at the time of presentation. The main concern is patients returning to harmful drinking post-transplantation despite a life-threatening illness and use of a scarce resource.

In the UK, a pilot programme was designed to evaluate the role of transplantation in severe alcoholic hepatitis, but unfortunately failed to meet the recruitment targets and was closed.

Complications

Severe alcoholic hepatitis is associated with a poor short-term survival.

Severity scoring systems discussed above detail the poor short-term survival among patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis. Long-term survival (i.e. 5-year survival) is particularly poor among patients who continue to drink following recovery.

Patients with alcoholic hepatitis and underlying cirrhosis may develop severe decompensation with associated organ failure. This is typically referred to as acute on chronic liver failure that is associated with a high mortality.

During the course of alcoholic hepatitis, particularly severe cases, patients are at increased risk of numerous complications.

- Hepatic encephalopathy

- Systemic infection: including spontaneous bacterial peritonitis

- GI bleeding: variceal bleeding (oesophageal/rectal)

- Coagulopathy and thrombocytopaenia

- Ascites: can develop even in the absence of decompensated cirrhosis and portal hypertension

- Multi-organ failure

Last updated: November 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback