Chronic liver disease

Notes

Overview

Chronic liver disease is caused by repeated insults to the liver, which can result in inflammation, fibrosis and ultimately cirrhosis.

Chronic liver disease (CLD) is the result of repeated damage to the liver by a variety of aetiological factors including alcohol, toxins, viruses and many others. CLD is generally defined as progressive liver dysfunction for six months or longer. The end result of chronic liver disease is cirrhosis, which describes irreversible liver remodelling.

The liver is involved in numerous functions that are essential to maintain the bodies homeostasis. To appreciate the sequelae of CLD we must understand the normal role of the liver in human health.

- Storage (i.e. glycogen, iron, vitamins)

- Breakdown (i.e. drugs, toxins, ammonia, bilirubin)

- Synthesis (i.e. bile, cholesterol, coagulation factors, growth factors)

- Immune function (i.e. innate immune protein production, resident immune cells)

CLD represents the fourth commonest cause of years of life lost in those aged under 75. It is the only major chronic condition with an increasing death rate.

The true prevalence is difficulty to quantify as the majority of CLD is asymptomatic and presents late. However, in England and Wales an estimated 600,000 patients have CLD. There has been a significant increase in hospital admissions relating to cirrhosis over the last two decades.

Aetiology

Chronic liver disease can arise due to a wide range of pathologies.

- Alcohol

- Viral

- Inherited

- Metabolic

- Non-alcohol fatty liver disease / Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

- Autoimmune

- Biliary

- Primary biliary cholangitis

- Primary sclerosing cholangitis

- Vascular

- Ischaemic hepatitis

- Budd-Chiari syndrome

- Congestive hepatopathy

- Medication

- Drug-induced liver injury

- Cryptogenic (no known cause)

- Other (many rare causes)

Natural history

Progressive liver injury culminates in cirrhosis, which describes irreversible liver remodelling.

Chronic liver disease may result from repeated insults that cause inflammation (i.e. chronic hepatitis) or cholestasis (i.e. impairment of bile flow). Excess deposition of fat in the liver (i.e. steatosis) can also promote an inflammatory response, which is seen in conditions like non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

Over time, chronic damage due to inflammation or cholestasis can lead to scarring known as fibrosis. In this situation, the normal liver architecture is replaced by fibrotic tissue and regenerative nodules. If the aetiological factor is removed or treated then some reversibility in liver function can occur depending on the extent of fibrosis.

If fibrogenesis continues then the end result is cirrhosis, which describes irreversible liver remodeling that is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Cirrhosis is often used synonymously with end-stage liver disease or advanced liver disease. Once the liver has developed cirrhosis there are two important clinical states:

- Compensated cirrhosis: patients are typically asymptomatic as a small amount of residual function allows the liver to continue carrying out normal function despite extensive damage.

- Decompensated cirrhosis: in this state the liver no longer has the capacity to carry out its normal functions, which results in multiple complications. If the insult is removed, the liver may 'recompensate' over time to a state of compensated cirrhosis.

Decompensated cirrhosis

Decompensated cirrhosis can result in significant morbidity and mortality and is characterised by the following:

- Coagulopathy (reducing clotting factor synthesis): evidence of bruising and deranged coagulation tests.

- Jaundice (impaired breakdown of bilirubin): yellow appearance of the skin and sclera

- Encephalopathy (poor detoxification of harmful substances): confusion

- Ascites (poor albumin synthesis and increased portal pressure due to scarring): accumulation of fluid in the abdominal cavity

- Gastrointestinal bleeding (increase portal pressure causing varices)

NOTE: Cirrhosis usually develops over many years and presents late. This means cirrhosis could be prevented through earlier detection and treatment. In fact, it is estimated that over 90% of liver disease is preventable.

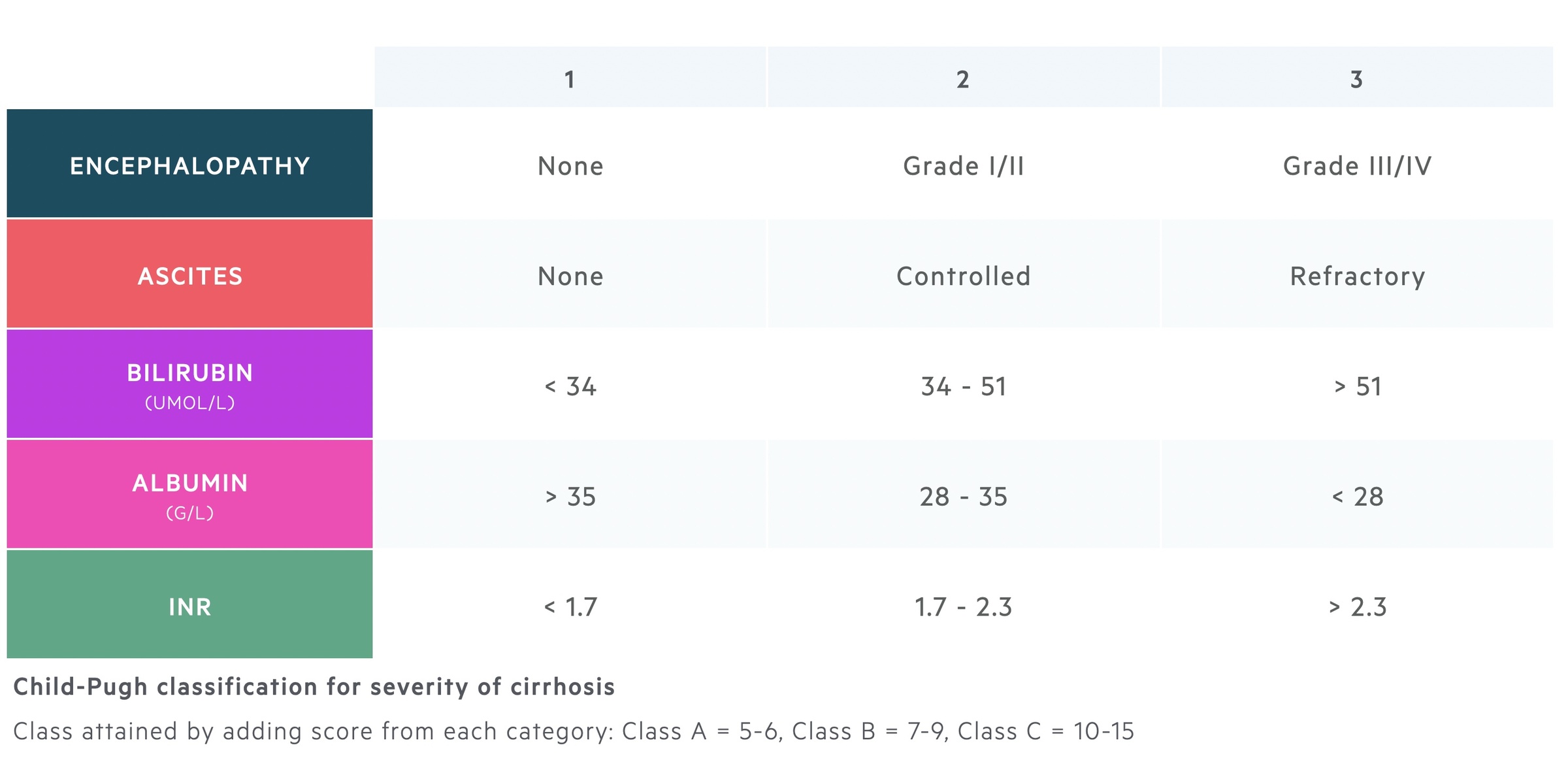

Child-Pugh score

The severity of cirrhosis can be graded using the Child-Pugh score.

The Child-Pugh (CP) classification is based on the clinical and biochemical features of decompensated cirrhosis.

The CP score was originally created as a prognostic tool for patients undergoing surgery for oesophageal varices. It has also been used to assess risk of mortality following abdominal surgery. For example, one review showed a 10% mortality among Child-Pugh A cirrhosis compared to 82% for those with Child-Pugh C cirrhosis.

The different classes reflect the severity of cirrhosis and provide an estimated one year survival.

- Class A: mild disease, one year survival 100%

- Class B: moderate disease, one year survival 80%

- Class C: severe disease, one year survival 45%

Clinical features

Classical stigmata of CLD include spider naevi, palmar erythema, jaundice, hair loss, leuconychia, asterixis, ascites.

Early clinical features are usually non-specific. They include anorexia, lethargy, weight loss, hepatomegaly, nausea or disturbed sleep pattern.

As patients develop more advanced disease, typical features of chronic liver disease develop. These clinical features are collectively referred to as ‘stigmata of chronic liver disease’. Among these, jaundice, ascites and encephalopathy are all features of decompensated cirrhosis.

Stigmata of chronic liver disease

- Caput medusa: distended and engorged superficial epigastric veins around the umbilicus.

- Splenomegaly: enlarged spleen.

- Palmar erythema: red discolouration on the palm of the hand, particularly over the hypothenar eminence.

- Dupuytren's contracture: thickening of the palmar fascia. Causes painless fixed flexion of fingers at the MCP joints (most commonly ring finger).

- Leuconychia: appearance of white lines or dots in the nails. Sign of hypoalbuminaemia.

- Gynaecomastia: development of breast tissue in males. Reduced hepatic clearance of androgens leads to peripheral conversion to oestrogen.

- Spider naevi: type of dilated blood vessel (i.e. telangiectasia) with central red papule and fine red lines extending radially. Due to excess oestrogen. Usually found in the distribution of the superior vena cava.

Features of hepatic decompensation

- Encephalopathy: confusion, often present with a flapping tremor (asterixis)

- Ascites: fluid within the peritoneal cavity.

- Jaundice: yellow pigmentation of skin and sclera

- GI bleeding: variceal bleeding or slow oozing from portal hypertensive gastropathy

- Coagulopathy: may see marked bruising due to raised INR

Diagnosis

Liver biopsy is still considered the gold-standard diagnostic method for the identification of cirrhosis.

During the diagnostic work-up, it is important to confirm both the presence of cirrhosis and the underlying aetiology (see 'non-invasive liver screen').

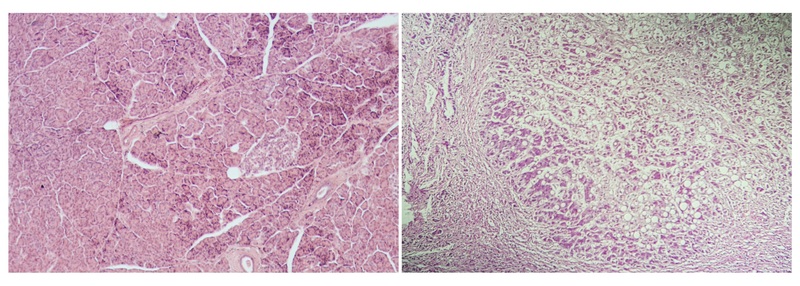

For the diagnosis of cirrhosis, a combination of biochemical tests, non-invasive techniques, imaging, and liver biopsy are used. Liver biopsy is considered the gold standard, however, it is invasive and associated with complications. Therefore, alternative investigations are used where possible (e.g. transient elastography).

Biochemical tests

Laboratory tests including liver function tests (LFTs), cannot be used to exclude cirrhosis. Less than 1 in 20 patients with asymptomatic cirrhosis will have an elevated transaminase (ALT/AST). However, they can be used to support the diagnosis of cirrhosis.

Biochemical tests may show subtle changes in patients with cirrhosis such as an elevated AST/ALT ratio, AST/platelet ratio, or presence of thrombocytopenia. Low platelets are supportive of portal hypertension that refers to increased pressure in the portal system due to liver scarring. The increased pressure leads to splenomegaly and causes hypersplenism (a process where the spleen removes blood cells too early and too quickly).

In decompensated cirrhosis, significant abnormalities may be seen (e.g. hyperbilirubinaemia, raised INR, low albumin).

Transient elastography

A quick painless test that assesses liver stiffness. It measures sound wave velocity using an ultrasound probe to indicate the ‘degree’ of fibrosis and thus the likelihood of cirrhosis.

Imaging

- USS: US is quick, inexpensive, and has a sensitivity of 65-95% for detection of CLD.

- CT: Provides a more detailed view of the abdominal viscera and is good for secondary findings (e.g. features of portal hypertension).

- MRI: Is emerging as a highly sensitive and specific modality for liver fibrosis.

Liver biopsy

A liver biopsy can be performed percutaneously using US or CT-guidance, or transjugular. A transjugular biopsy approaches the liver via the hepatic vein. It is completed if contraindications to percutaneous liver biopsy are present (e.g. ascites, coagulopathy).

Liver biopsies are usually reserved for specific cases:

- Liver disease of unknown aetiology

- Differentiating between acute and chronic disease

- Unable to differentiate between fibrosis and cirrhosis

Normal liver architecture (left) compared to a cirrhotic liver (right)

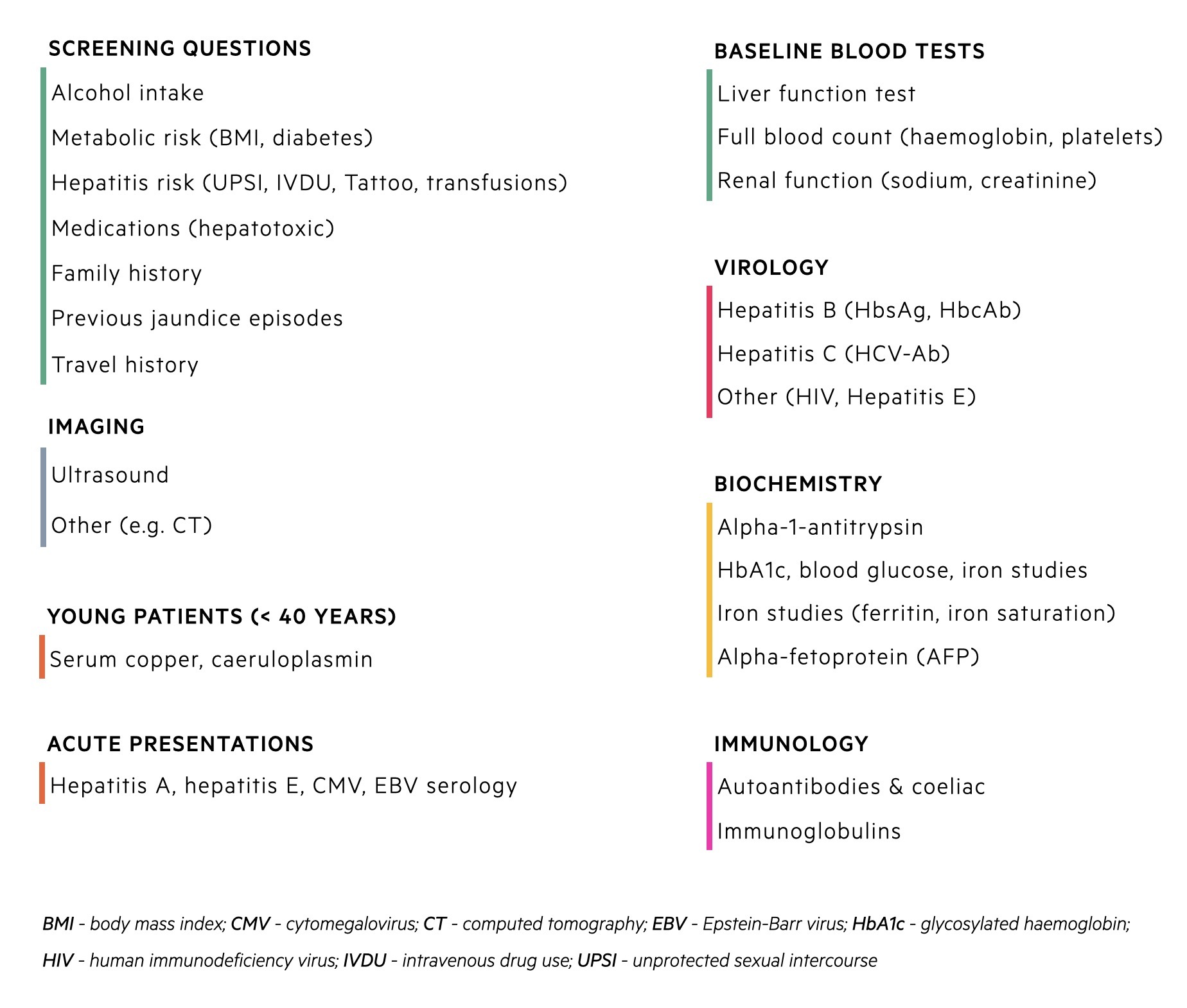

Non-invasive liver screen

Due to the wide number of pathologies a ‘non-invasive liver screen’ is often used to determine the aetiology.

A non-invasive liver screen refers to screening questions, biochemical tests, and imaging to assess patients with suspected liver disease. It is employed when blood tests show abnormal liver function or CLD is suggested from clinical examination/imaging. An example of all the relevant questions and biochemical tests that should be requested are shown in the diagram below.

Management

Management involves treating the underlying pathology, preventing progression and managing complications.

The key strategy in managing patients with CLD is removing the aetiological factor leading to progressive liver damage. This may be a simple intervention like alcohol cessation, removal offending medications or use of anti-viral therapies in chronic hepatitis. For specific treatments of conditions that cause chronic liver disease see our notes on individual topics.

Unfortunately, many conditions do not have a therapeutic option and there are limited interventions available to prevent the overall progression of CLD. Therefore, many strategies are focused on targeting key pathogenic events that occur as a complication of cirrhosuis.

We discuss the key management strategies for the major complications that occur in cirrhosis.

Hepatic encephalopathy

Hepatic encephalopathy describes neuropsychiatric disturbances in the context of CLD.

It is thought to occur because the liver is unable to clear harmful substances that are produced by bacteria within the gastrointestinal tract (e.g. ammonia). Due to portal hypertension, there is shunting of these harmful substances away from the liver into the systemic circulation at portosystemic collaterals (i.e. where the portal venous system joins the systemic venous system), although other mechanisms are postulated. This results in reversible encephalopathy (i.e.state of abnormal brain function). Constipation is the main driver of encephalopathy.

- First-line treatments: involves laxatives (i.e. lactulose 15-20 mls QDS) to maintain bowel motions. Should aim for 2-3 bowel motions per day.

- Second-line treatments: involves the long-term use of antibiotics (i.e. rifaximin) to reduce the proportion of ammonia-producing colonic bacteria.

Ascites

Ascites describes fluid accumulation within the peritoneal cavity.

It develops due to a combination of portal hypertension and loss of oncotic pressure (hypoalbuminaemia). Due to widespread vasodilatation and underperfusion of the kidneys, the renin-angiotension-aldosterone systems (RAAS) is active leading to excess water and sodium reabsorption that exacerbates ascites.

- Aldosterone antagonists: Treatment involves the use of aldosterone antagonists (e.g. spironolactone) that can be combined with loop diuretics (i.e. furosemide).

- Paracentesis: Patients with tense (grade III) ascites require large volume paracentesis that involves percutaneous drainage of ascites with human albumin solution cover to prevent post-drainage circulatory dysfunction.

Refractory ascites may require transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPSS), which is an interventional procedure that creates a connection between a hepatic vein and an intrahepatic portal vein. A PTFE graft is then left between this connectin to allow blood to flow from the portal vein to the inferior vena cava under little resistance.

Gastrointestinal bleeding

Oesophageal varices occur secondary to portal hypertension.

Cirrhosis leads to the development of portal hypertension because of extensive scarring and increased pressure through the portal system. Consequently, blood is shunted into the systemic circulation at portosystemic sites (i.e. where the portal venous system joins the systemic venous system). Portosystemic sites include:

- Lower oesophagus

- Upper anal canal

- Umbilicus

- Bare area of the liver

- Retroperitoneum

Increased pressure at the portosystemic site at the lower oesophagus leads to dilated, tortuous vessels known as varices that are at high risk of bleeding. The management of oesophageal varices depends on whether they have led to acute GI bleeding or not.

- Primary prophylaxis (i.e. no bleeding): Involves the use of non-selective beta-blockers (i.e. propranolol, carvedilol) to reduce portal pressure in patients with cirrhosis and significant varices.

- Acute variceal haemorrhage (i.e. acute bleeding): Medical emergency, ABCDE management, endoscopic variceal band ligation. See BSG UK Guidelines for the Management of Variceal Haemorrhage in Cirrhotic Patients.

- Secondary prophylaxis (i.e. after bleeding): After the management of an acute bleed patients should be offered to enter a banding surveillance programme and non-selective beta blockers (i.e. propranolol, carvedilol)

Cases of refractory bleeding may require an urgent transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPSS) to reduce the portal pressure (discussed above).

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis

SBP refers to infection within ascitic fluid.

SBP is a serious medical condition with high mortality. It is defined as a predominantly neutrophilic ascitic white cell count (WCC) >250/mm3.

- Antibiotics: Follow local guidance, should not be delayed, ascitic tap should be obtained prior.

- Human albumin solution: Helps to prevent the development of acute kidney injury and hepatorenal syndrome.

- Prophylaxis: Patients at risk of, or following confirmed, SBP should be managed with long-term prophylactic antibiotics (e.g. rifaximin).

Hepatocellular carcinoma

Patients with cirrhosis or chronic hepatitis B are high risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). HCC is a primary liver cancer that occurs most commonly in patients with cirrhosis.

Due to the high risk of HCC, patients with cirrhosis should be invited to undergo six-monthly surveillance with ultrasound +/- Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) blood test.

Transplantation

Liver transplantation is potentially a life-saving treatment for patients with chronic liver disease or associated complications.

Within the UK, patients deemed suitable for transplantation undergo formal assessment that reviews both their indications and contraindications to transplant. Current criteria for selection is based on the United Kingdom model for end-stage liver disease (UKELD) score, which is an adaptation of the original model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score.

The UKELD is based on serum creatinine, sodium, bilirubin and INR. The minimum criteria for listing a patient for liver transplantation is a score ≥ 49, which represents a 9% one-year mortality without a transplant. Other indications for liver transplantation, outside the UKELD score, are based on the presence of hepatocellular carcinoma with specific criteria and variant syndromes (e.g. diuretic resistant ascites).

Complications

Cirrhosis is associated with significant morbidity and mortality from a number of complex, interlinked, complications.

- Hepatic encephalopathy

- Ascites

- Hyponatraemia

- Gastrointestinal bleeding (i.e. variceal bleed)

- Bacterial infections (i.e. SBP)

- Acute kidney injury

- Hepatocellular carcinoma

- Hepatorenal syndrome

- Hepatopulmonary syndrome

- Acute-on-chronic liver failure

Last updated: October 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback