Hepatitis B

Notes

Introduction

Hepatitis B is caused by the hepatitis B virus (HBV) and can lead to both acute and chronic liver disease.

Worldwide, hepatitis B is a major health problem. An estimated 240 million people have chronic hepatitis B, however, in the UK the prevalence is low (0.3%).

It is caused by the hepatitis B virus (HBV), which may lead to both acute and chronic infection. Chronic hepatitis B (CHB) can lead to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Hepatitis B may cause an acute or chronic infection.

- Acute: can occur at any age. Majority of patients have a subclinical or anicteric (no evidence of jaundice) illness. In adults and older children, usually a self-limiting illness. In young children, more likely to develop chronic infection.

- Chronic: failure to clear the virus after acute infection. Defined as persistence of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) for >6 months. HBsAg is a viral protein that can be measured in the blood.

Epidemiology

The overall prevalence of HBV in the UK is estimated at 0.3%.

This relates to around 180,000 patients with chronic hepatitis B. The annual incidence of acute hepatitis B in the UK is 0.68 per 100,000 population.

Low prevalence countries are generally defined by a prevalence < 2%. These include Western Europe, United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. High prevalence countries are generally defined by a prevalence > 8%. These include Southeast Asia, China, Pacific islands and Sub-Saharan Africa.

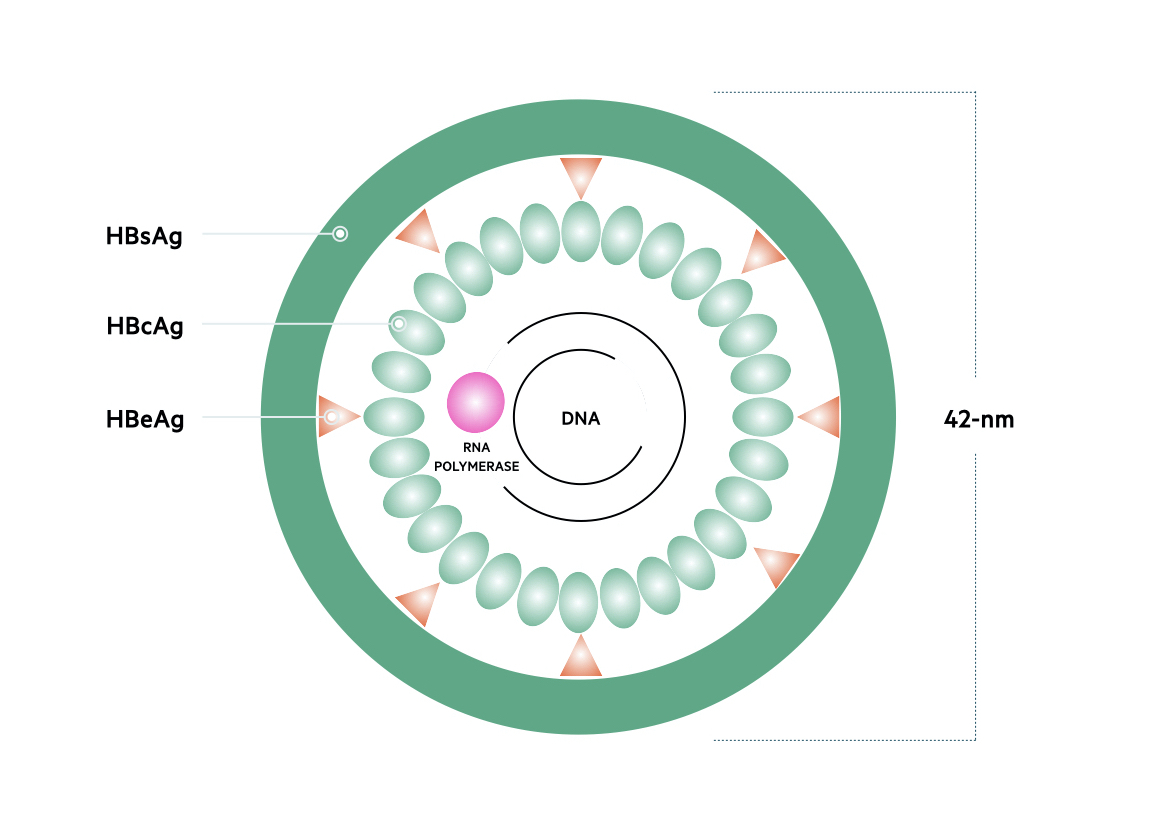

Hepatitis B virus

Hepatitis B virus is an enveloped DNA virus that has eight distinct genotypes.

HBV belongs to the family of Hepadnaviridae that includes a number of other viruses (e.g. Woodchuck hepatitis virus). It is a DNA virus that contains a nucleocapsid and outer envelope. Its small DNA genome is contained within the nucleocapsid.

Genome

The genetic material of HBV is 3200 base pairs long and constructed into circular, partially doubled-stranded DNA. Based on the nucleotide sequence of the 3200 base pairs, HBV is classified into eight separate genotypes termed A-H. These genotypes are distributed differently throughout the world. The predominant genotype on the UK is A.

There are four major genes within the HBV genome.

- Surface (S) gene: encodes the small surface protein HBsAg

- Core (C) gene: encodes the hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg), which also helps form the e antigen (HBeAg)

- Polymerase (P) gene: encodes DNA polymerase/reverse transcriptase

- X gene: encodes the hepatitis B x (HBx) protein

Proteins

The protein products of all four genes are important in HBV DNA replication and viral particle assembly.

- HBsAg: needed for construction of the outer HBV envelope

- HBcAg: composed within the nucleocapsid that contains the viral DNA.

- HBeAg: acts as an immune decoy to promote viral persistence. Presence is a marker of viral replication and infectivity.

- DNA polymerase: involved in the synthesis of DNA molecules. Has reverse transcriptase activity, which means it can form DNA from RNA.

- X protein: a transcriptional regulator that promotes cell cycle progression.

Replication

Once infected, HBV enters hepatocytes within the liver. Within hepatocytes the viral particle removes its out envelope and forms covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA). This DNA forms a template for transcription of the HBV proteins. cccDNA enters the nucleus of the cell where transcription takes place.

Once transcribed, core proteins, polymerase proteins and pregenomic RNA are packaged into core particles. Pregenomic RNA is then reverse transcribed into HBV DNA whilst surface proteins are attached to create the outer envelope. The full viral particle may then be secreted to infect other hepatocytes.

Transmission

HBV can be transmitted perinatally, parenterally (e.g. infected needles), percutaneously or though sexual contact.

High prevalence regions

In endemic regions, the majority of HBV cases are transmitted perinatally or during early childhood. Infection between mother and neonate typically occurs at the time of birth or close contact afterwards. Transmission in utero can occur, but is uncommon. In early childhood, transmission is usually through close household contact (e.g. abrasions, cuts, sharing toothbrushes). The majority of UK cases are found within patients who have migrated to the UK and acquired HBV in these ways in their country of birth.

Low prevalence regions

In low prevalence countries, like the UK, infection is more commonly acquired through sexual contact or sharing contaminated needles. HBV can also be transmitted within a healthcare environment through contaminated surgical instruments or accidental needle stick injury. Due to national screening, risk of HBV following blood transfusion has almost been eliminated.

Risk of chronic infection

Risk of progression to chronic infection has an inverse relationship with age.

- Perinatal transmission: 90% risk of chronic infection

- Early childhood transmission: 25-50% risk of chronic infection

- Adult transmission: < 5% risk of chronic infection

Natural history

Chronic hepatitis B has a well documented natural history that consists of five main phases.

HBV is not directly cytopathic. Liver injury is due to the interaction between virus and host immune response. HBV leads to an acute infection, which is most commonly subclinical. Persistent infection leads to chronic hepatitis B, which is characterised by five phases.

Acute infection

The age and immune status of the patient are important determinants of acute to chronic progression following infection with HBV. The majority (~70%) of patients have a subclinical or anicteric hepatitis. The remaining 30% present acutely with jaundice (icteric hepatitis). Fulminant hepatic failure is uncommon, occurring in 0.1-0.5 % of cases.

In adults with acute HBV, less than 5% will develop chronic infection. Spontaneous clearance of hepatitis B is characterised by loss of HBsAg. This is usually accompanied by development of Hepatitis B surface antibodies (HBsAb or Anti-HBs), Hepatitis B core antibodies (HBcAb) and undetectable HBV DNA levels.

Even in patients who ‘clear’ the virus, there is still risk of ‘reactivation’ in the presence of immunosuppression. This is because HBV can persist at low levels, being held in check by the host immune response.

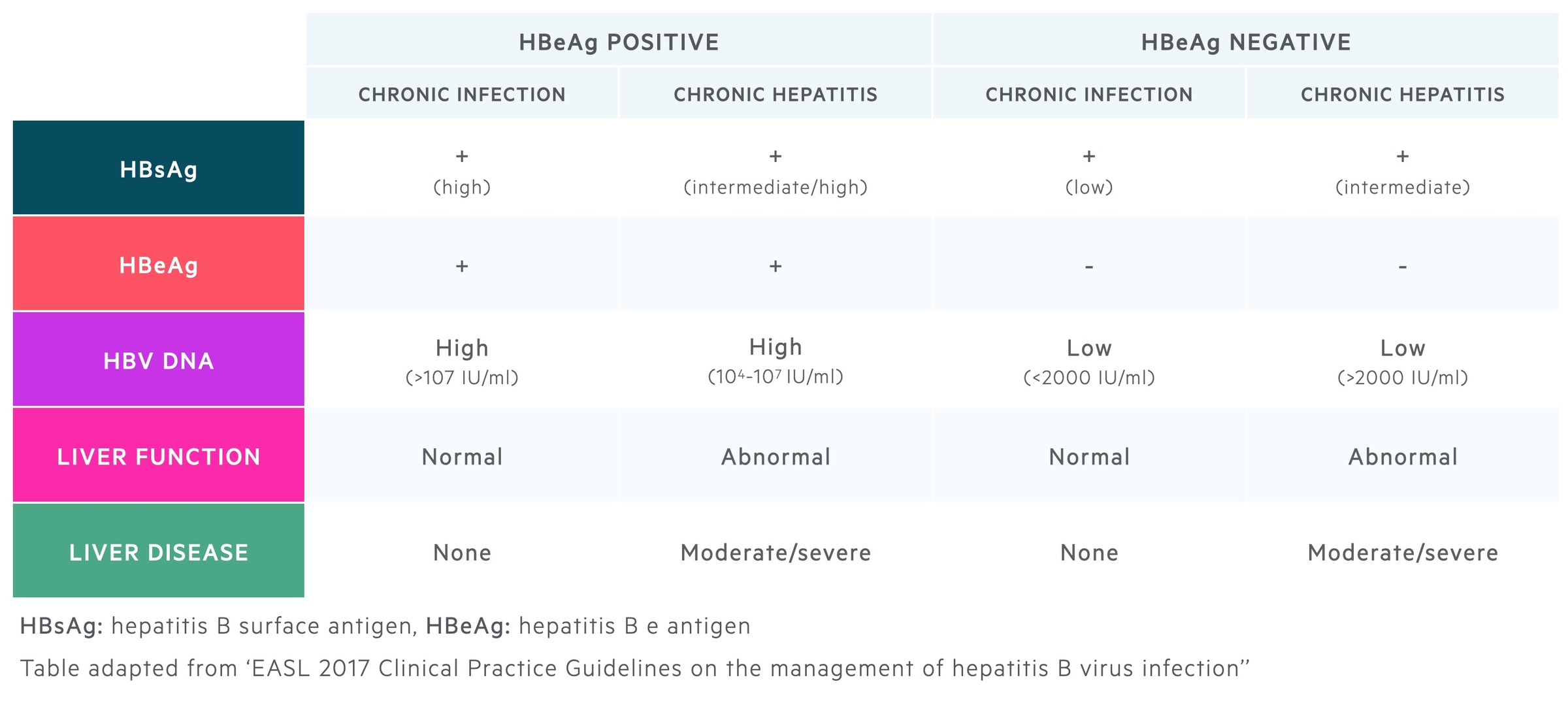

Chronic infection

Chronic hepatitis B is characterised by five phases, which are divided based on HBsAg and HBeAg status, HBV DNA levels, liver function tests (e.g. alanine aminotransferase - ALT) and presence or absence of liver disease (e.g. inflammation/fibrosis). These phases are not necessarily sequential.

The five phases include:

- Phase 1 - HBeAg +ve chronic infection (previously ‘immune tolerant’)

- Phase 2 - HBeAg +ve chronic hepatitis (previously ‘immune reactive/clearance’)

- Phase 3 - HBeAg -ve chronic infection (previously ‘inactive carrier’)

- Phase 4 - HBeAg -ve negative chronic hepatitis (previously ‘reactivation phase’)

- Phase 5 - HBsAg negative phase (previously ‘occult hepatitis B infection’)

HBeAg positive chronic infection

Characterised by minimal liver inflammation and high viral replication. Highly contagious.

HBeAg positive chronic hepatitis

Characterised by moderate to severe inflammation in the liver and accelerated progression to fibrosis. Usually occurs many years after first phase. Can progress directly to HBeAg negative chronic hepatitis.

HBeAg negative chronic infection

Characterised by significant viral suppression and absence of significant liver disease. Favourable prognosis if minimal liver injury developed before immune clearance. Fibrosis may be present on biopsy despite low levels of HBV DNA.

HBeAg negative chronic hepatitis

Characterised by moderate to severe liver inflammation, low rate of spontaneous clearance and genetic mutations in the HBV genome that impair expression of HBeAg.

HBsAg negative (spontaneous clearance)

Characterised by recovery from hepatitis B infection. Estimated annual rate of HBsAg clearance is 1%. Prognosis following clearance is excellent in patients who clear the virus before 50 year old or before progression to cirrhosis. HBV can occasionally be detected at low levels.

This phase is characterised by the following markers:

- HBsAg: negative

- HBsAb: negative/positive

- HBcAb: positive

- HBV DNA levels: absent/very low

- Liver function tests: normal

- Liver disease: absent inflammation (cirrhosis may develop before clearance)

Features of acute infection

The majority of patients with acute hepatitis B have a subclinical or anicteric illness.

The incubation period for acute hepatitis B, which describes the time between acquisition and development of symptoms, is 1-4 months. If clinical features develop they usually last 1-3 months, although fatigue may persist.

There is a wide spectrum of presentation in acute hepatitis B.

- Subclinical hepatitis

- Anicteric hepatitis

- Icteric hepatitis

- Fulminant hepatic failure (rare)

Subclinical hepatitis

Patients will be asymptomatic and unlikely to be identified unless blood tests are taken for an alternative problem. Patients will not realise they are infected. If acquired during adulthood, very low risk of chronic hepatitis B.

Anicteric hepatitis

Typically presents with a non-specific illness in the absence of jaundice.

- Malaise

- Anorexia

- Nausea

- Fever

- Right upper quadrant pain

- Vomiting

Icteric hepatitis

Features similar to anicteric hepatitis but also present with jaundice.

Fulminant hepatitis failure

Rare in patients with acute hepatitis B. Acute liver failure is characterised by jaundice, confusion and coagulopathy in the absence of underlying liver disease (i.e. cirrhosis).

For more information see acute liver failure.

Features of chronic infection

The majority of patients with chronic hepatitis B are asymptomatic.

Features of fatigue and right upper quadrant pain may be present, however, the majority of patients with chronic hepatitis B are asymptomatic. Patients can develop exacerbations that may be asymptomatic or mimic acute hepatitis B. Patients may also present with complications of chronic hepatitis B (e.g. cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma).

There is a wide spectrum of presentation in chronic hepatitis B.

- Asymptomatic carrier state

- Chronic hepatitis

- Cirrhosis

- Decompensated cirrhosis

Asymptomatic carrier state

Patients will be asymptomatic with significantly suppressed viral activity. This correlates to the HBeAg negative chronic infection stage, previously known as ‘inactive carrier’.

Chronic hepatitis

Patients may present with a wide range of symptoms depending on the severity of hepatitis and underlying liver impairment. Exacerbations of chronic hepatitis B may mimic acute hepatitis B.

- Asymptomatic

- Malaise

- Anorexia

- Nausea

- Fever

- Right upper quadrant pain

- Vomiting

- Jaundice

Cirrhosis

Patients may have features of underlying cirrhosis (e.g. hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, portal hypertension). Stigmata of chronic liver disease (e.g. spider naevi) are rare in chronic hepatitis B compared to alcoholic liver disease.

Decompensated cirrhosis

Decompensated cirrhosis refers to an inability of the liver to carry out normal function. It is characterised by development of ascites, encephalopathy, jaundice, coagulopathy and GI bleeding.

For more information see chronic liver disease.

Extra-hepatic manifestations

This refers to a variety of clinical presentations occurring outside the liver that are typically seen in chronic hepatitis B.

- Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN): found in 10-30%. Systemic vasculitis of medium and small vessels. Characterised by small aneurysm formation that can rupture. Multi-system disease affecting skin, joints, GI tract, kidneys and more.

- Glomerulonephritis: More common in children. Causes a range of glomerulonephritides including membranous, mesangiocapillary and focal proliferative. For more information see notes on glomerulopathies.

- Mixed cryoglobulinaemia: systemic inflammation due to cryoglobulins in the serum, which are immunoglobulins that precipitant at low temperature. Associated with digital ulcers, Raynaud’s, purpura and peripheral neuropathy. More common in hepatitis C.

- Papular acrodermatitis: seen in young children. Typically presents with an eruption of a erythematous, symmetrical, maculopapular rash on the thighs, buttocks, outer arms and face. Non-itchy.

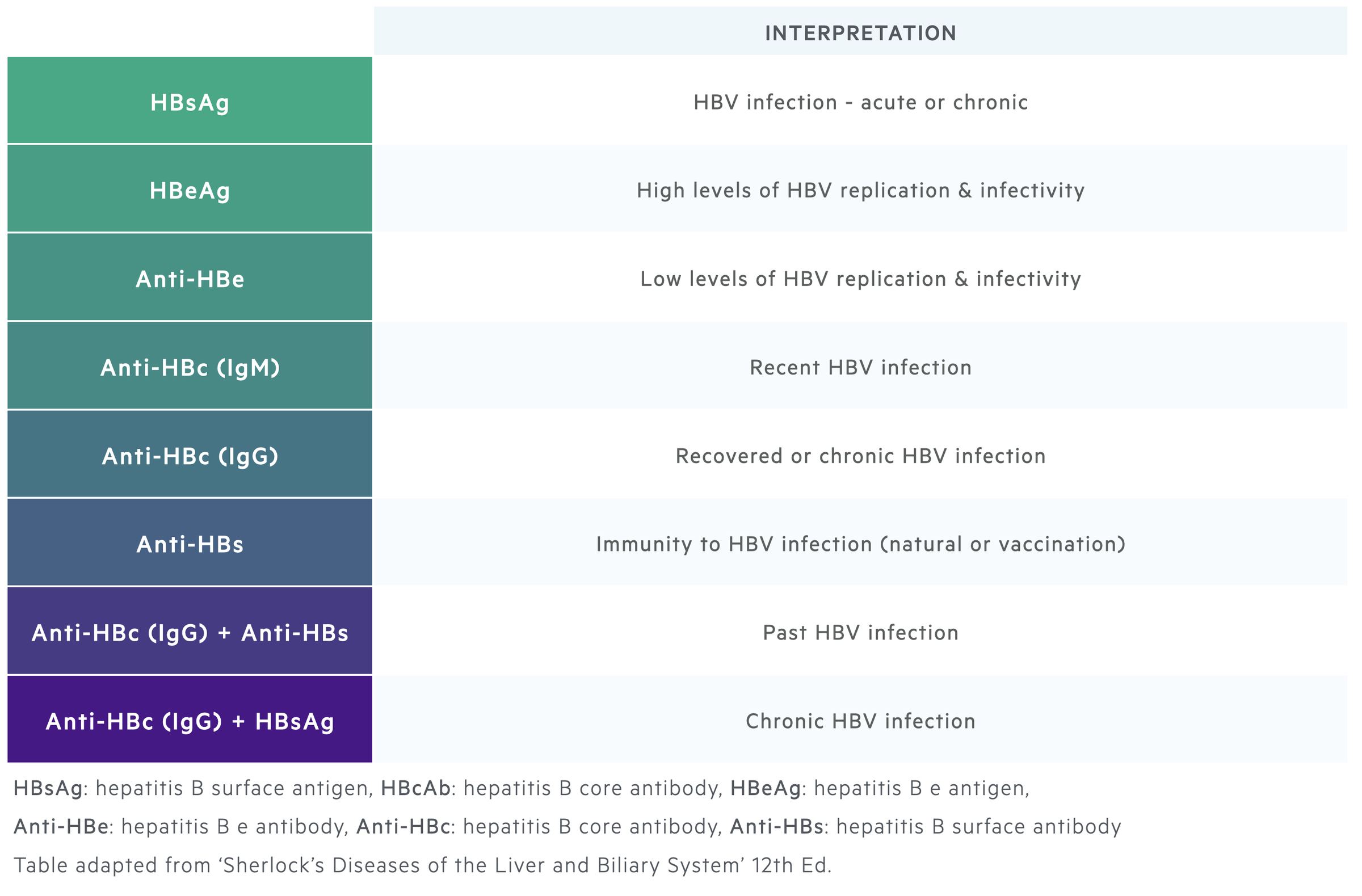

Serological diagnosis

Correct diagnosis of HBV requires assessment of serological markers and HBV DNA levels.

Serological markers of infection, which include antigens and antibodies, are important to make a diagnosis of hepatitis B. They can determine acute or chronic infection, phase of chronic infection and previous infection following spontaneous clearance.

HBV DNA levels are needed to confirm the diagnosis and to determine the phase of infection in patients with chronic infection. The degree of liver injury can be assessed with both non-invasive and invasive tests.

HBsAg and Anti-HBs

HBsAg is the hallmark of HBV infection. Its presence for >6 months is used to define chronic hepatitis B. HBsAg can be detected 1-10 weeks following acquisition of the virus and usually up to 6 weeks before clinical presentation with hepatitis.

Clearance of HBsAg is usually followed by appearance of anti-HBs antibodies. HBsAg clearance marks recovery from hepatitis B. Anti-HBs antibodies usually persist for life conferring long-term immunity. However, patients are still at risk of reactivation if the immune system is suppressed.

HBcAg and Anti-HBc

HBcAg cannot be detected in the blood. Therefore, antibodies directed against the core antigen (anti-HBc) are used as a surrogate marker of infection.

IgM anti-HBc antibodies indicate acute infection as IgM marks the initial antibody response. IgG anti-HBc antibodies subsequently rise and will be seen in patients who are chronically infected with hepatitis B or in those who have recovered.

Interpretation:

- Chronic infection: IgG Anti-HBc (+), Anti-HBs (+/-), HBsAg (+)

- Recovery: IgG Anti-HBc (+), Anti-HBs (+), HBsAg (-)

- Vaccination: IgG Anti-HBc (-), Anti-HBs (+), HBsAg (-)

HBeAg and Anti-HBe

The hepatitis e antigen is a marker of viral replication and thus infectivity. It is needed to classify chronic hepatitis B into the correct phase. Seroconversion from HBeAg (+) to HBeAg (-) with Anti-HBe antibodies is associated with a significant fall in HBV DNA levels and patients usually enter into the inactive carrier state.

HBV DNA levels

HBV DNA levels are used as markers of infectivity and reflect hepatitis B viraemia. We can detect HBV levels down to 10 IU/mL. DNA levels can be detected up to 3 weeks before the appearance of HBsAg in acute infection.

HBV DNA levels fluctuate during chronic infection. They are used to determine the phase of chronic hepatitis B and form part of treatment indications.

Investigating liver injury

Liver injury and inflammation can be determined using biochemical markers and non-invasive or invasive tests of fibrosis.

Establishing the degree of liver injury is important to accurately classify the phase of chronic hepatitis B and to assess for long-term damage (e.g. cirrhosis).

Biochemical markers

Liver function tests can be completed, which reflect the presence of ongoing inflammation within the liver. There is usually a hepatic pattern with a rise in ALT and AST. Occasionally, even with normal liver function tests there may be evidence of ongoing inflammation on biopsy.

Non-invasive tests of fibrosis

Transient elastography refers to a quick, painless test that assesses liver stiffness. It measures sound wave velocity using an ultrasound probe to indicate the ‘degree’ of fibrosis and thus likelihood of cirrhosis.

Invasive tests of fibrosis

Liver biopsy (percutaneous or transjugular) can be completed to assess the extent of inflammation and fibrosis within the liver.

A liver biopsy may be performed to rule out another cause of liver disease e.g. autoimmune hepatitis or non-alcoholic fatty liver disease), in those with persistently elevated ALT but relatively low DNA levels, and those at risk of advanced liver disease despite relatively normal blood tests.

Acute hepatitis B management

The majority of cases of acute hepatitis B are self-limiting so management is supportive.

Most cases of acute hepatitis B are self-limiting. Acute hepatitis B is a notifiable disease, which means it needs to be reported. This helps to prevent further infection and identify exposed contacts. Patients can be managed with supportive measures and usually do not need antiviral therapy.

Rarely, acute hepatitis B may cause a profound acute hepatitis or even fulminant hepatic failure. Patients who are deeply jaundiced, have evidence of encephalopathy or coagulopathy (all features of acute liver failure) require urgent admission and assessment. These patients should be discussed with a tertiary transplant unit.

Antiviral therapy

Occasionally patients can be considered for treatment with nucleos(t)ide analogues (NA), which are discussed further below. Interferon is an antiviral agent used in chronic hepatitis B. It should not be used in acute hepatitis B as it can worsen inflammation.

NA options can include:

- Entecavir

- Tenofovir

- Lamivudine

Indications for treatment

In general, patients with severe liver injury or a protracted illness should be considered for NAs. Indications can include:

- Severe or fulminant hepatitis

- Co-infection with hepatitis C or D

- Immunocompromised patients

- Elderly patients

Chronic hepatitis B management

Treatment of chronic hepatitis B aims to suppress HBV replication and lead to remission of liver disease.

Current licensed treatments for hepatitis B can only suppress HBV replication, they do not eradicate the virus. The aims of treatment are to prevent cirrhosis, decompensated liver disease and HCC. Treatment of chronic hepatitis B is a specialist area and should be guided by a hepatologist with a specialist interest in viral hepatitis.

Indications for treatment

There are various indications to start treatment, which are based on HBV DNA levels, liver function tests (i.e. ALT levels) and severity of liver disease.

- HBeAg-positive or negative chronic hepatitis B

- HBeAg-positive or negative chronic HBV infection & family history of HCC or cirrhosis

- HBeAg-positive or negative chronic HBV infection & extra-hepatic manifestations

- HBeAg-positive chronic HBV infection if older than 30 years

- Cirrhosis (compensated or decompensated) and detectable DNA levels

- HBV DNA >20,000 IU/mL and ALT x2 ULN

Antiviral therapy

The two main treatments in chronic hepatitis B are pegylated interferon (PegIFN) and nucleos(t)ide analogues (NA). The treatment of choice is long-term administration of a NA with a high barrier to resistance (i.e. low likelihood of resistance developing).

- Nucleos(t)ide analogues: act primarily by inhibition of reverse transcription of pregenomic HBV RNA into HBV DNA within hepatocytes. Multiple available including lamivudine, entecavir, and tenofovir among others. Entecavir and tenofovir have a high barrier to resistance. Good safety profile and well-tolerated. Given orally for long-term viral suppression. May be stopped in selected cases.

- Pegylated Interferon: PegIFN has both antiviral and immunomodulatory activity. Exact mechanism is unclear. Thought to induce specific genes that interrupt with HBV replication cycle. Given weekly as subcutaneous injection for 48 weeks. Poor tolerability due to side-effects (flu-like illness, fatigue, weight loss, psychiatric disturbance, bone marrow suppression). Contraindicated in decompensated cirrhosis. High variability in response.

Drug resistance

Given that NAs are given long-term for viral suppression, development of antiviral drug resistance is a major limitation. Suggested by a rise in serum HBV DNA levels or detection of HBV DNA after a period of control. May lead to flare of hepatitis +/- decompensation. Classic mutations are seen in HBV and can be tested for in the lab.

Management of cirrhosis

Patients with evidence of cirrhosis secondary to hepatitis B should be managed like any patient with chronic liver disease. For more information on management see notes on chronic liver disease.

Transplantation

Patients with cirrhosis secondary to hepatitis B may be candidates for liver transplantation and should be referred for transplant assessment if appropriate. For more information on transplantation see notes on chronic liver disease.

Prevention

HBV can be prevented by education and universal vaccination.

Within the UK, hepatitis B vaccination now forms part of the universal vaccination programme for children. The vaccine is usually given as a combination vaccine (6 in 1) at 8, 12 and 16 weeks of age.

The two most widely used HBV vaccines are recombinant vaccines, which include Recombivax and Engerix-B. Recombinant vaccines are developed by inserting genetic material from the pathogen that encodes the antigen of interest into bacterial or yeast cells. The antigen can then be purified and used as the active ingredient in the vaccine. Hepatitis B vaccines are mainly yeast derived and contain the small S protein (component of the outer envelope).

Indications for HBV vaccine

- All newborns

- All children and adolescents not vaccinated at birth

- High risk adults (e.g. healthcare workers, intravenous drug users, haemodialysis patients, etc)

Hepatitis B immune globulin

Hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG) is a substance that contains high levels of hepatitis B surface antibody. It can be given within hours of exposure to prevent infection. It should be given alongside the HBV vaccine.

HBIG is given to sexual contacts of patients with acute HBV, babies born to mothers with hepatitis B and people with parenteral exposure to hepatitis B (e.g. needlestick). HBIG also has a role in prevention of reinfection following liver transplantation for HBV.

Complications

The major complications of hepatitis B are cirrhosis, decompensated liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma.

The aim of treatment and monitoring in hepatitis B is to prevent liver-related complications including cirrhosis, decompensated liver disease and HCC.

Among those who progress to cirrhosis, there is a 2-5% annual risk of developing HCC, which has a poor prognosis unless treated early. Due to chronic necroinflammation from HBV, up to 50% of HCC cases occur in the absence of cirrhosis. In addition, co-infection with other hepatotropic viruses (Hepatitis C, Hepatitis D), human immunodeficiency virus or excess alcohol consumption all increase the risk of cirrhosis and HCC.

Prognosis

Without treatment, the estimated 5-year incidence of cirrhosis in adults with chronic hepatitis B is up to 20%.

Globally, up to 1 million patients die from hepatitis B each year. Patients who are HBeAg-negative due to seroconversion (i.e. development of Anti-HBe) with low or undetectable HBV DNA levels have better outcomes due to the slower rate of disease progression and less development of cirrhosis and HCC. Five-year survival rates among people with untreated decompensated cirrhosis can be as low as 15%.

One of the major predictors of developing HCC is a high viral load over time. Patients with cirrhosis need to be screened for HCC every 6 months. In those without cirrhosis, screening is less clear cut, but should be completed in high risk patients.

Last updated: November 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback