Primary sclerosing cholangitis

Notes

Overview

Primary sclerosing cholangitis is an immune-mediated disease characterised by cholestasis, bile duct strictures and hepatic fibrosis.

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is an immune-mediated chronic cholestatic liver disease. It causes progressive inflammation, fibrosis and destruction of both the intra- and extra-hepatic bile ducts. This leads to problems with poor bile flow (cholestasis), narrowing of bile ducts (stricturing) and ultimately chronic scarring (cirrhosis).

PSC is one of many causes of bile duct damage and narrowing that are broadly termed ‘cholangiopathies’. Sclerosing cholangitis is a cholangiopathy that can be divided into primary and secondary:

- Primary: refers to PSC. Absence of another identifiable cause.

- Secondary: refers to any condition causing bile duct damage and biliary obstruction. Numerous causes such IgG4-sclerosing cholangitis, cholangiocarcinoma or recurrent cholangitis.

Epidemiology

PSC is more commonly seen in men.

Among Northern Europeans, the incidence of PSC is estimated between 0.91-1.3 per 100,000 person years. The condition occurs more commonly in men (~70%) with an average age at diagnosis of 40 years old. Women typically present at an older age. PSC is uncommon in children.

Among Northern Europeans, inflammatory bowel disease (Ulcerative colitis > Crohn’s disease) is seen in 62-83% of patients with PSC. These percentages may be lower in other ethnic groups and populations.

Aetiology

The exact cause of PSC remains unknown.

PSC is considered a progressive autoimmune disorder that is strongly associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). An immune-mediated reaction develops that causes bile duct damage. This inflammatory response is induced by multiple mechanisms in genetically predisposed individuals who are exposed to certain environmental stimuli. It is postulated that a chronic inflammatory response occurs in response to recurrent exposure to bacteria within the portal system, accumulation of toxic bile acids or ischaemic bile duct injury.

Association with IBD

In Northern European populations, inflammatory bowel disease is commonly identified in patients with PSC (62-83%). However, only a small proportion of patients with IBD have PSC (< 10%). Both ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (usually due to Crohn’s colitis) are associated with PSC. For more information see below chapter (PSC and IBD).

Small duct PSC

PSC is characterised by bile duct injury and narrowing of both the intra- and extra-hepatic bile ducts. A variant of PSC exists known as ‘small duct' PSC. This condition is characterised by cholestatic liver enzymes (e.g. raised ALP and gGT), typical histological features of PSC, but normal appearing bile ducts on cholangiography. Patients with small duct PSC usually require liver biopsy.

Patients with small duct PSC have a better prognosis, although some patients will develop classical PSC over time.

Pathophysiology

PSC is a progressive cholestatic liver disease.

PSC is a progressive cholestatic disorder that results in bile duct injury, stricturing and liver fibrosis. It can affect both the intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts.

- Intrahepatic bile ducts: small bile ducts proximal to the right and left hepatic ducts

- Extrahepatic bile ducts: large bile ducts starting at the right and left hepatic ducts

Patients are usually asymptomatic during the early course of disease, but this progresses overtime with development of non-specific symptoms (e.g. right upper quadrant pain, fatigue, pruritus, jaundice, fever). Patients develop bile duct narrowing that leads complications of cholestasis including pruritus, obstructive jaundice and recurrent bacterial cholangitis. Importantly, there is an increased risk of cholangiocarcinoma (CCA). With continued inflammation there is progressive liver scarring, development of cirrhosis and subsequent decompensation. Without liver transplantation, median survival following diagnosis is 10-12 years.

Clinical features

PSC may be asymptomatic, particularly during the early stages of the disease.

PSC is commonly asymptomatic during the early stages of disease. It may be detected incidentally on imaging or following an abnormal blood test. As symptoms develop they are typically related to cholestasis.

Symptoms

An estimated 50% are symptomatic at the time of diagnosis.

- Fatigue

- Pruritus

- Features of cholangitis (see below)

Signs

- Hepatomegaly

- Splenomegaly

- Excoriations

- Stigmata of chronic liver disease

Cholangitis

Patients with PSC are at risk of cholangitis. This refers to inflammation/infection of the biliary system, which is characterised by a triad of fever, right upper quadrant pain and jaundice (Charcot’s triad).

- Fever

- Right upper quadrant pain

- Jaundice

- Rigors

- Night sweats

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of PSC is based on liver biochemistry and cholangiography.

A formal diagnosis of PSC can be made based on the presence of cholestatic liver function tests (i.e. raised ALP and gGT) and typical appearance on magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). Secondary causes of sclerosing cholangitis require exclusion (see differential diagnosis).

There are no characteristic autoantibodies or liver markers that are diagnostic of PSC like in other conditions (e.g. PBC/AIH). A background of IBD is supportive of the diagnosis of PSC.

Liver biochemistry

Liver function tests (LFTs) can be used to detect pathology within the liver. Up to 75% of patients with PSC have abnormal LFTs. LFTs can be interpreted to determine the pattern of liver injury. This may be ‘hepatic’ or ‘cholestatic’:

- Hepatic pattern: raised transaminases (ALT and AST). Typically due to acute hepatitis (e.g. viral, autoimmune, alcohol).

- Cholestatic pattern: raised ALP and gGT. Typically due to biliary stasis or obstruction (e.g. PSC, PBC, gallstone disease).

PSC classically results in a cholestatic pattern of liver injury, which is characterised by elevations in ALP. Transaminases (ALT/AST) may be mildly raised, but significant elevations should prompt investigation for a dual pathology (e.g. autoimmune hepatitis). An elevated bilirubin may be seen in up to 40%, usually a poor prognostic feature.

Cholangiography

Traditionally, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) was used to make a formal diagnosis of PSC. This shows the typical beading appearance due to multifocal stricturing. ERCP is an invasive procedure that involves upper GI endoscopy and cannulation of the biliary system through the ampulla of Vater to enable injection of contrast.

There are majors risk associated with ERCP including cholangitis and pancreatitis. To avoid theses risks, diagnosis of PSC is now based on MRCP. MRCP is non-invasive and very sensitive at picking up the characteristic multifocal stricturing and bile duct dilatation that is seen in PSC.

Classic changes seen on MRCP:

- Biliary stricturing: may be focal or diffuse. Majority of patients have strictures affecting both intra- and extrahepatic ducts

- Biliary dilatation: may be intrahepatic and/or extrahepatic

ERCP is reserved for patients who also need therapeutic intervention (e.g. to treat a bile duct stricture) or who cannot undergo MRI.

Differential diagnosis

It is important to exclude secondary causes of sclerosing cholangitis before making the diagnosis.

PSC needs to be differentiated from others causes of sclerosing cholangitis, collectively known as secondary sclerosing cholangitis. Most secondary causes can be excluded based on clinical, biochemical and imaging assessment.

Secondary causes of sclerosing cholangitis:

- Inflammatory: IgG4-sclerosing cholangitis, pancreatitis

- Malignancy: cholangiocarcinoma, hilar lymphadenopathy, head of pancreas tumour

- Infection: recurrent pyogenic cholangitis, biliary infestation (e.g. flukes)

- Stones: choledocholithiasis

- Other: drugs, papillary stenosis

Investigations

Investigations are used to exclude an underlying cause, determine degree of liver injury and assess for complications.

Bloods

Routine bloods tests are essential to determine the extent of liver disease and screen for secondary causes. PSC is characterised by a ‘cholestatic’ pattern on LFTs and absence of autoantibodies.

- Full blood count

- Urea & electrolytes

- Bone profile

- Liver function tests

- Coagulation

- Ca19.9: a tumour marker that may be requested if there is suspicion of CCA. It provides evidence of the possible diagnosis of cancer, but is not reliable as screening or confirmatory test.

A non-invasive liver screen is appropriate to ‘screen’ for an underlying cause of liver disease. This is useful to exclude a secondary cause or a co-factor contributing to liver disease. For more information see Chronic liver disease notes.

Imaging

MRCP is the imaging modality of choice. Ultrasound may be useful in the initial work-up of abnormal liver function tests but does not contribute to the diagnosis of PSC. CT imaging may be reserved for detection of complications (e.g. hepatocellular carcinoma or cholangiocarcinoma).

Non-invasive assessment of liver fibrosis

An enhanced liver fibrosis (ELF) serological score or a transient elastography measure of liver stiffness can be used to identify patients with advanced fibrosis. These non-invasive tools can be used to monitor for liver fibrosis and development of cirrhosis.

Endoscopy

Upper GI endoscopy may be needed in patients with PSC due to bile duct strictures or complications of portal hypertension (e.g. oesophageal varices). In addition, patients with PSC require investigation of inflammatory bowel disease if it is not already known due to the high association.

- Gastroscopy: can be used to screen for varices and provided therapeutic banding

- ERCP: predominantly used as a therapeutic tool to manage dominant bile duct stricture or investigate cholangiocarcinoma.

- Colonoscopy: used to assess for inflammatory bowel disease in all patients and for surveillance in those with a known diagnosis.

Example of cholangiogram during ERCP.

Image courtesy of J. Guntau (Wikimedia commons)

Histology

A liver biopsy is rarely needed in the diagnosis of PSC. It may be used to investigate possible small duct PSC, if an overlap syndrome is suspected or the diagnosis is unclear. On histology, PSC is characterised by periductal fibrosis, bile duct proliferation, periportal inflammatory, dutopaenia and varying degrees of fibrosis.

Overlap syndromes

When features of PSC occur concurrently with autoimmune hepatitis, it is known as an ‘overlap syndrome’.

Overlap syndromes are a challenging area. They are defined as the concurrent presence of two autoimmune conditions at the same time or during the course of the illness. PSC may overlap with features of autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) and IgG4-related diseases. AIH may also be seen to overlap with primary biliary cholangitis.

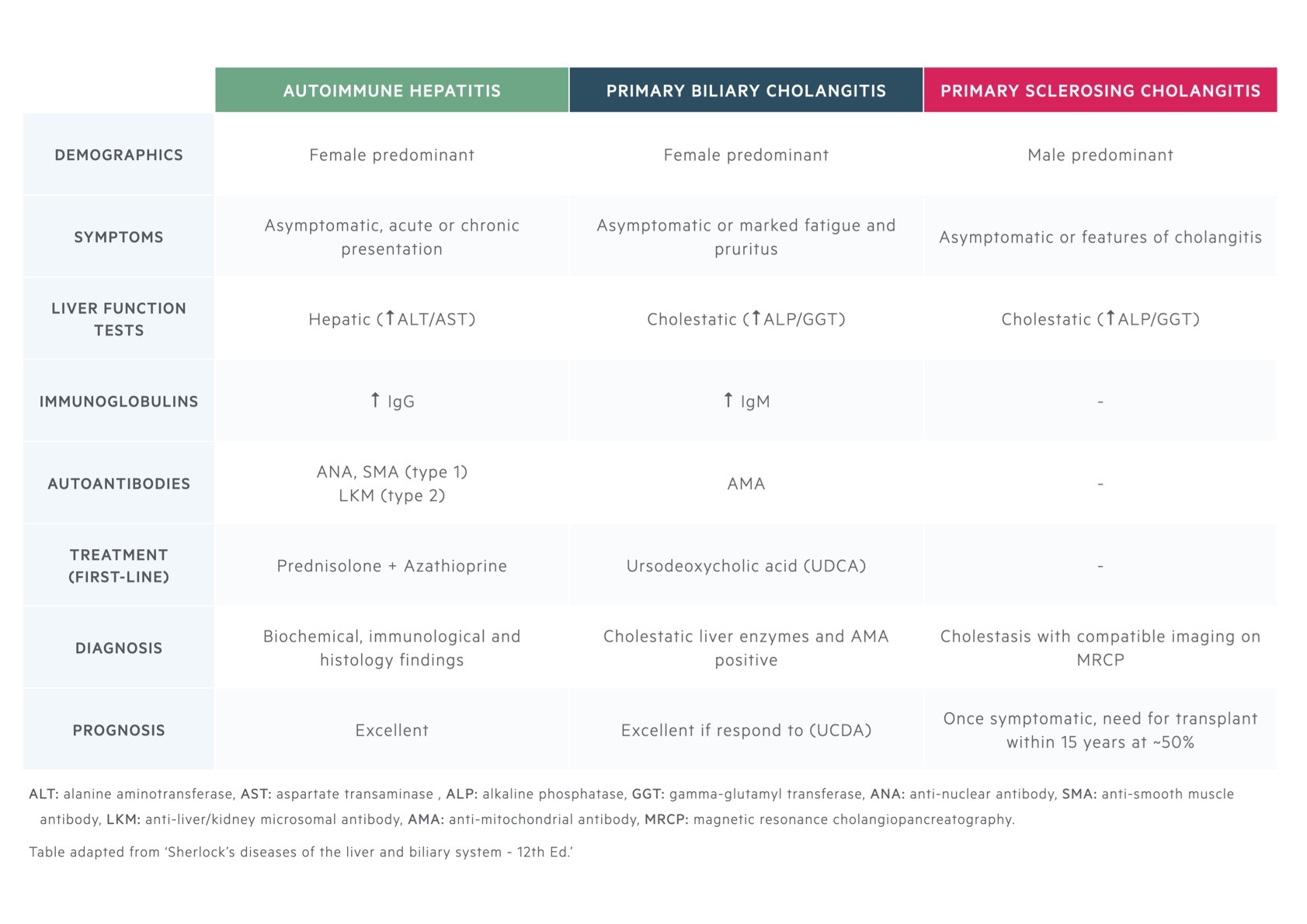

AIH, PSC and PBC are all autoimmune liver diseases. The defining characteristics of each are summarised.

PSC/AIH overlap

Based on MRI findings, up to 12% of adults with AIH have evidence of PSC. There are no specific criteria and diagnosis is based on classic imaging and histological changes.

PSC/IgG4 overlap

It is unclear whether IgG4-sclerosing cholangitis overlaps with PSC or it is an entirely separate condition. IgG4-sclerosing cholangitis causes a clinical picture very similar to PSC, which is characterised by elevated IgG4 levels and there may be other features of IgG4-related disease (e.g. autoimmune pancreatitis).

PSC & IBD

Both Crohn’s disease and Ulcerative colitis are associated with PSC.

The association between IBD and PSC depends on geographical locations. In Northern Europeans, IBD may be identified in up to 4/5ths of patients with PSC compared to only 1/5th elsewhere in the world. It is typically associated with extensive colitis, which may be Ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s colitis. UC is more commonly identified.

PSC is most commonly identified after a diagnosis of IBD. Treatment of IBD has no impact on the overall progression of PSC. In fact, PSC may develop following a colectomy for UC and IBD may develop after a liver transplantation for PSC. It is highly variable. All patients who are diagnosed with PSC need to undergo assessment for IBD that should include a colonoscopy and biopsies.

Management

Liver transplantation is the only effective treatment that alters survival in PSC.

Unfortunately, there are no proven pharmacological treatment that have an effect on disease progression or survival in PSC. The principle treatment is liver transplantation. Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) among other medications have been trialled but none alter the natural history.

Medical management

Medical treatments are aimed at managing the complications of PSC including cholangitis, metabolic bone disease (e.g. osteoporosis) and pruritus (itching).

- Cholangitis: patients are often very unwell with overt sepsis. Antibiotics and fluids are the principle treatment. Patients may require urgent decompression of an obstructed biliary system with ERCP or percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC).

- Bone disease: patients with cholestatic liver diseases are at increased risk of osteopaenia and osteoporosis. This should be screened for and treated. Concomitant vitamin D deficiency should be treated.

- Pruritus: itching can significantly affect quality of life and can be hard to control. First line treatment includes the bile-acid sequestrant cholestyramine. Second line options are rifampicin and naltrexone.

Endoscopic therapy

Patients with PSC are at risk of significant biliary strictures and recurrent cholangitis. This means there is opportunity for endoscopic intervention using ERCP to treat extrahepatic strictures through balloon dilatation or placements of stents.

ERCP is also critical in the diagnostic work-up of cholangiocarcinoma. Brushings from strictures can be taken at the time of ERCP to look for malignant cells.

Liver transplantation

Liver transplantation is the principle treatment in patients with advanced liver disease secondary to PSC. The overall 5-year survival is excellent, although there is risk of recurrent disease in the transplanted liver (i.e. the graft) that occurs in 10-40%.

Patients with advanced liver disease require referral to a liver transplant centre for formal transplant assessment that may be conducted as an inpatient or outpatient depending on the severity of liver disease. Not all patients are suitable for transplantation owing to age, co-morbidities and/or presence of malignancy (e.g. cholangiocarcinoma).

Management of advanced liver disease

Patients with advanced liver disease will require management of cirrhosis and its complications. For more information on the management of cirrhosis see Chronic liver disease notes.

Cholangiocarcinoma

Cholangiocarcinoma is the most common cause of death in patients with PSC. There is a total lifetime risk of 20% with an incidence of 0.6-1.5% per year. Around 50% of cases of cholangiocarcinoma associated with PSC are identified within a year of diagnosis of PSC.

Features of cholangiocarcinoma include upper abdominal pain, worsening liver function tests, jaundice or a raised Ca19.9. It can be difficult to detect on imaging due to local invasion of bile ducts rather than formation of a tumour in the early stages. Patients with a suspected cholangiocarcinoma require MRCP. This should be followed by ERCP and brushings if there is a dominant biliary stricture (can be difficult to differentiate between an inflammatory and malignant stricture). In the absence of a dominant stricture, a CT should be requested looking for a tumour. All cases should be referred to this specialist HPB MDM for further management.

Surveillance

Colorectal, biliary and hepatic malignancies are a major complication of PSC, which require frequent surveillance.

Colorectal cancer

There is a high incidence of colorectal cancer (CRC) in patients with PSC who also have coexistent IBD. Patients with IBD and PSC require annual surveillance colonoscopy.

Biliary malignancy

Patients with PSC are at increased risk of biliary malignancies (e.g. cholangiocarcinoma, biliary polyps).

Any new or changing symptoms suggestive of a cholangiocarcinoma should warrant CT or MRI to investigate further. However, routine surveillance is not recommended. An annual ultrasound scan of the gallbladder should be performed in patients with PSC. If polyps are identified, treatment should be directed by specialist HPB MDM.

Hepatic malignancy

Patients with cirrhosis are at increased risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma. Any patient with cirrhosis should have 6-monthly HCC surveillance with ultrasound +/- alpha fetoprotein.

Complications

Recurrent cholangitis due to biliary strictures is one of the main complications of PSC.

Classic complications of PSC relate to stricturing and cholestasis.

- Cholangitis

- Cholangiocarcinoma: lifetime risk up to 20%. Most common cause of death in PSC in patients not undergoing transplant.

- Chronic liver disease

- Metabolic bone disease (e.g. osteoporosis)

- Poor nutrition

- Fatigue and depression

- Pruritus

Prognosis

In PSC, the median time from diagnosis to death or liver transplantation is 10-22 years.

Overall, PSC is a progressive disease that will lead to cirrhosis and associated complications. It tends to have a worse prognosis in those who are symptomatic or have concurrent IBD. Nevertheless, it is difficult to determine the exact prognosis in PSC due to an unpredictable disease course with a median time to transplantation or death or 10-22 years.

Last updated: November 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback