Hepatitis D

Notes

Overview

Hepatitis D is caused by the defective hepatitis D RNA virus that needs hepatitis B for replication.

Hepatitis D virus (HDV) is a unique RNA virus that can only establish infection in the human liver with the help of Hepatitis B virus (HBV). HDV has an outer envelope that contains the HBV surface antigen (HBsAg). Therefore, it can only establish infection in HBsAg-positive patients.

There are two key terms to recognise with HDV infection:

- Coinfection: acute hepatitis D infection acquired at the same time of hepatitis B infection. Typically indistinguishable from acute hepatitis B alone.

- Superinfection: development of acute hepatitis D infection in a patient with pre-existing hepatitis B infection. Usually more severe illness and higher risk of chronic infection (>90% of cases).

Hepatitis D virus

Hepatitis D is a defective RNA virus, often referred to as ‘delta’ virus or ‘delta’ agent.

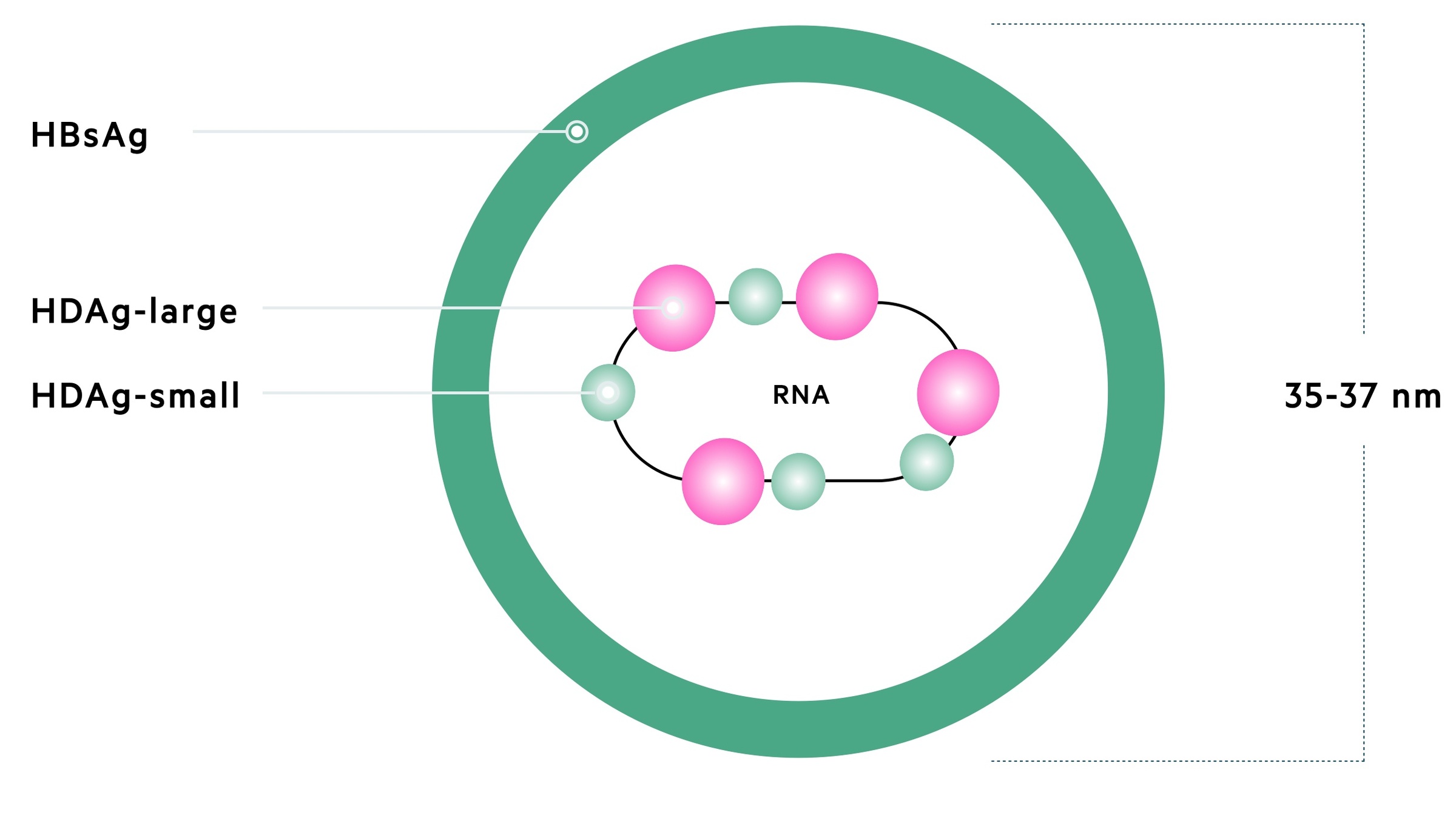

Structure

Hepatitis D is the smallest animal virus at 35-37 nm, which belongs to its own genus known as Deltavirus. HDV contains single-stranded, circular RNA, a nucleocapsid that incorporates the Hepatitis D antigen (HDAg) and an envelope formed by HBsAg.

Genome

HDV contains around 1700 nucleotides in its single-stranded, circular RNA. It contains one open-reading frame (portion of DNA with no stop codons, which can encode a gene) that encodes HDAg.

There are eight distinct genotypes of HDV. Genotype 1 is detected worldwide and the predominant type in Europe.

Protein

HDAg has a large/long and small/short form:

- HDAg-L: important in virus assembly and can inhibit replication

- HDAg-S: involved in viral replication. Binds directly to HDV RNA.

Replication

For replication, HDV requires host RNA polymerase activity and for assembly it requires hepatitis B virus. Without hepatitis B infection, virion assembly and release cannot be completed as HBV provides the outer envelope.

Epidemiology

Hepatitis D can only be transmitted to patients infected with hepatitis B virus.

Hepatitis D has a worldwide distribution with 15-20 million carriers of HBsAg infected with HDV. Individuals with hepatitis D are always dually infected with hepatitis B.

Endemic regions include Mediterranean areas, Middle East, Central and Northern Asia, East Africa, the Amazon Basin and Pacific islands. The UK has a low prevalence of hepatitis D (0-5%) and it is usually confined to high risk groups (e.g. intravenous drug users, historical recipients of multiple blood transfusions).

Transmission

Transmission of HDV is similar to HBV, through sexual contact, close household contact (e.g. abrasions, cuts, sharing toothbrushes), perinatally (although vertical transmission rare) or parenterally (e.g. contaminated needles). Patients who have previously had HBV with evidence of antibodies to the hepatitis B surface antigen (Anti-HBs) and negative HBsAg are not at risk of HDV.

Hepatitis D may be transmitted in two ways:

- Simultaneously with hepatitis B (coinfection)

- In a patient with preexisting hepatitis B (superinfection)

Natural history

Hepatitis D is not directly cytopathic and only able to replicate in the liver.

Like other hepatotropic viruses, HDV is not directly cytopathic and liver injury occurs due to host immune-mediated injury.

Hepatitis D may lead to either acute or chronic infection.

Acute infection

The natural history of acute HDV depends on whether it is coinfection or superfinfection.

- Coinfection: variable clinical presentation ranging from mild to fulminant hepatitis. Usually a self-limited infection as HDV will not outlive the transient HBsAg positive status. Usually indistinguishable from acute hepatitis B. As with acute hepatitis B in adults, it usually results in complete recovery and rarely causes chronic infection (<2%).

- Superinfection: more commonly there is an overt, severe hepatitis that is occasionally fulminant (i.e. acute liver failure). May present as an exacerbation of chronic hepatitis B, or new presentation of hepatitis in a previously unknown HBsAg carrier. Likely to become chronic hepatitis D in >90% of cases.

Chronic infection

The natural history of chronic hepatitis D is highly variable from asymptomatic to presentation with features of decompensated cirrhosis. Up to 50% report a history of previous hepatitis, which correlates with superinfection. The majority of liver damage that occurs in patients with hepatitis D and B coinfection is from HDV. This is because hepatitis D suppresses viral replication of HBV.

Chronic hepatitis D is a severe disease with persistently abnormal liver biochemistry (i.e. liver function tests) and increased risk of progression to cirrhosis. Up to 80% of chronically infected patients develop cirrhosis within 5-10 years. A high proportion will subsequently die from liver-related complications (e.g. hepatocellular carcinoma, decompensated cirrhosis).

Clinical features

Presentation of hepatitis D is variable ranging from asymptomatic carrier to mild-to-moderate hepatitis to complications of cirrhosis.

Asymptomatic carrier

Patients will be asymptomatic and usually have evidence of subclinical hepatitis (e.g. deranged liver function tests). Usually seen in patients with chronic hepatitis D.

Hepatitis

In coinfection, symptoms are indistinguishable from acute hepatitis B. Clinical hepatitis ranges in severity and may be anicteric (without jaundice). In Superinfection there is usually a more severe hepatitis with onset of jaundice.

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Anorexia

- Malaise

- Right upper quadrant pain

- Fever

- Jaundice

These clinical features may be present in patients with chronic hepatitis D and persistent hepatitis.

Cirrhosis

Patients who progress to chronic hepatitis D may have features of underlying cirrhosis (e.g. hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, portal hypertension). Stigmata of chronic liver disease (e.g. spider naevi) may be present

Decompensated cirrhosis

Decompensated cirrhosis refers to an inability of the liver to carry out normal function. It is characterised by the development of ascites, encephalopathy, jaundice, coagulopathy and GI bleeding.

For more information see chronic liver disease.

Diagnosis & investigations

Diagnosis of hepatitis D is based of serological markers and HDV RNA levels.

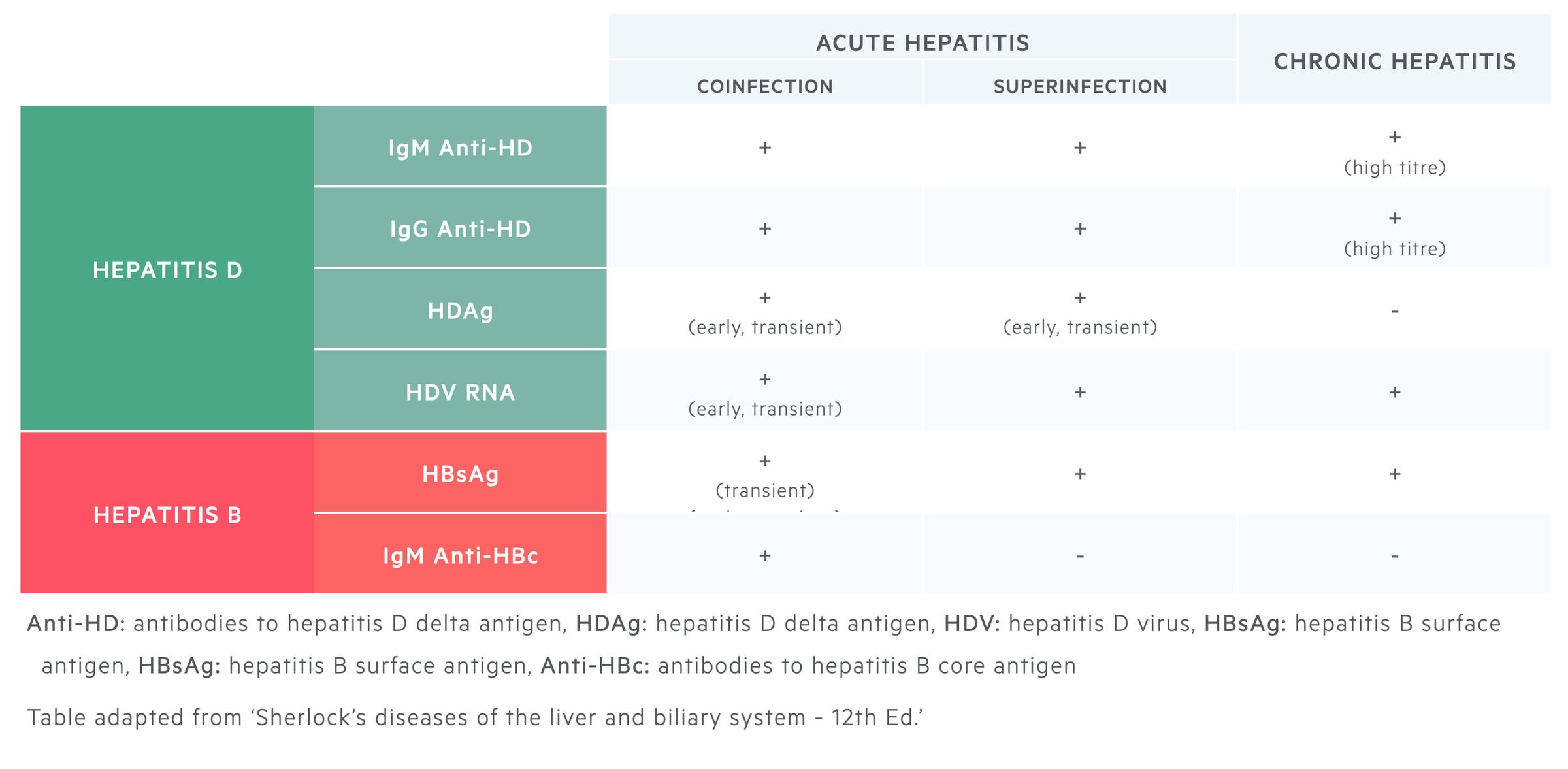

Hepatitis D and B serological markers and viral levels are important to distinguish between both acute and chronic infection, as well as coinfection and superinfection.

Coinfection

Characterised by markers of acute hepatitis B infection and acute hepatitis D infection.

- Markers of acute hepatitis B: IgM antibodies to core antigen (IgM Anti-HBc) + HBsAg. Other markers include hepatitis B e antigen or the antibody directed against it (Anti-HBe) and IgG anti-HBc.

- Markers of acute hepatitis D: IgM antibodies to delta antigen (IgM Anti-HD) +/- IgG antibodies to delta antigen (IgG Anti-HD). Serum HDAg may be transiently detected. HDV RNA usually detectable.

See hepatitis B for more information on the diagnosis of hepatitis B.

Superinfection

The absence or presence of IgM Anti-HBc at only low titres is the key differentiating factor between coinfection and superinfection.

Features of superinfection:

- Hepatitis B markers: Low/Absent IgM Anti-HBc + IgG Anti-HBc + HBsAg.

- Hepatitis D markers: Transient high HDAg levels + HDV RNA + IgM/IgG anti-HD.

Chronic infection

Chronic hepatitis D infection is characterised by persistence of IgM Anti-HD. High levels of this antibody are associated with HDV-induced liver injury and decrease in this antibody predict resolution.

IgG anti-HD, IgM anti-HD and HDV RNA levels are all found in chronic hepatitis D. HDAg is found in the liver, but due to interaction with antibodies, may not be detected in the blood.

Assessment of liver injury

Patients with evidence of acute hepatitis or chronic liver disease need a full liver disease screen requested and imaging of the liver (e.g. ultrasound or computed tomography).

Basic blood tests including full blood count, urea & electrolytes, bone profile, c-reactive protein, coagulation (inc. INR) and liver function tests are needed to assess for inflammation and the livers synthetic function.

Non-invasive tests (e.g. elastography) or invasive tests (e.g. liver biopsy) can be used to assess for the degree of fibrosis and/or presence of cirrhosis.

Management

Only the use of interferon-alpha has been shown to be beneficial in the treatment of chronic hepatitis D.

The ultimate aim of management is to eradicate HDV, induce HBV seroconversion with loss of HBsAg and prevention of long-term complications including cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). However, treatment is often unsatisfactory and many patients relapse after discontinuation.

Acute hepatitis D management

There is no specific treatment for acute hepatitis D and management is supportive. Patients should be monitored for progression to fulminant hepatitis that may require transplantation. Unfortunately, the majority of patients with superinfection will develop chronic hepatitis D.

Chronic hepatitis D management

The only available drug that is considered effective against HDV is interferon alfa (IFNa), which is usually given as pegylated IFN. Unfortunately, only a small number of patients treated with IFN clear the virus.

Indications for treatment:

- Detectable HDV RNA, AND

- Evidence of active liver disease (e.g. raised ALT or inflammation on biopsy)

Pegylated IFN is usually given for a course of one year and patients are managed at specialist centres. Successful treatment is characterised by a fall in HDV RNA levels and loss of HDAg in the liver. Treatment is contraindicated in patients with advanced or decompensated liver disease. The only option in these patients is liver transplantation if appropriate.

Following transplantation, reinfection can be reduced by the use of hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HIBG) and antiviral therapy to prevent reinfection with hepatitis B.

Prevention

Vaccination against HBV would render patients immune to HDV. Therefore, patients high risk of developing hepatitis D (e.g. intravenous drug users) should be given the hepatitis B vaccine. For more information see hepatitis B.

Complications

The major complications are cirrhosis, decompensated cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma.

Prevention is a key part of hepatitis D management due to the poor response to treatment and increased risk of cirrhosis and related complications.

Prognosis

The prognosis is excellent for patients with coinfection.

Adult patients who develop coinfection with hepatitis D and B have a good prognosis. This is because the infection is usually self-limiting and there is a low chance of chronicity. However, superinfection is associated with a significant increase in morbidity and mortality with a very high chance of chronicity and associated complications.

Last updated: November 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback