Stroke

Notes

Overview

A stroke is a cerebrovascular event that is caused by abnormal perfusion of cerebral tissue.

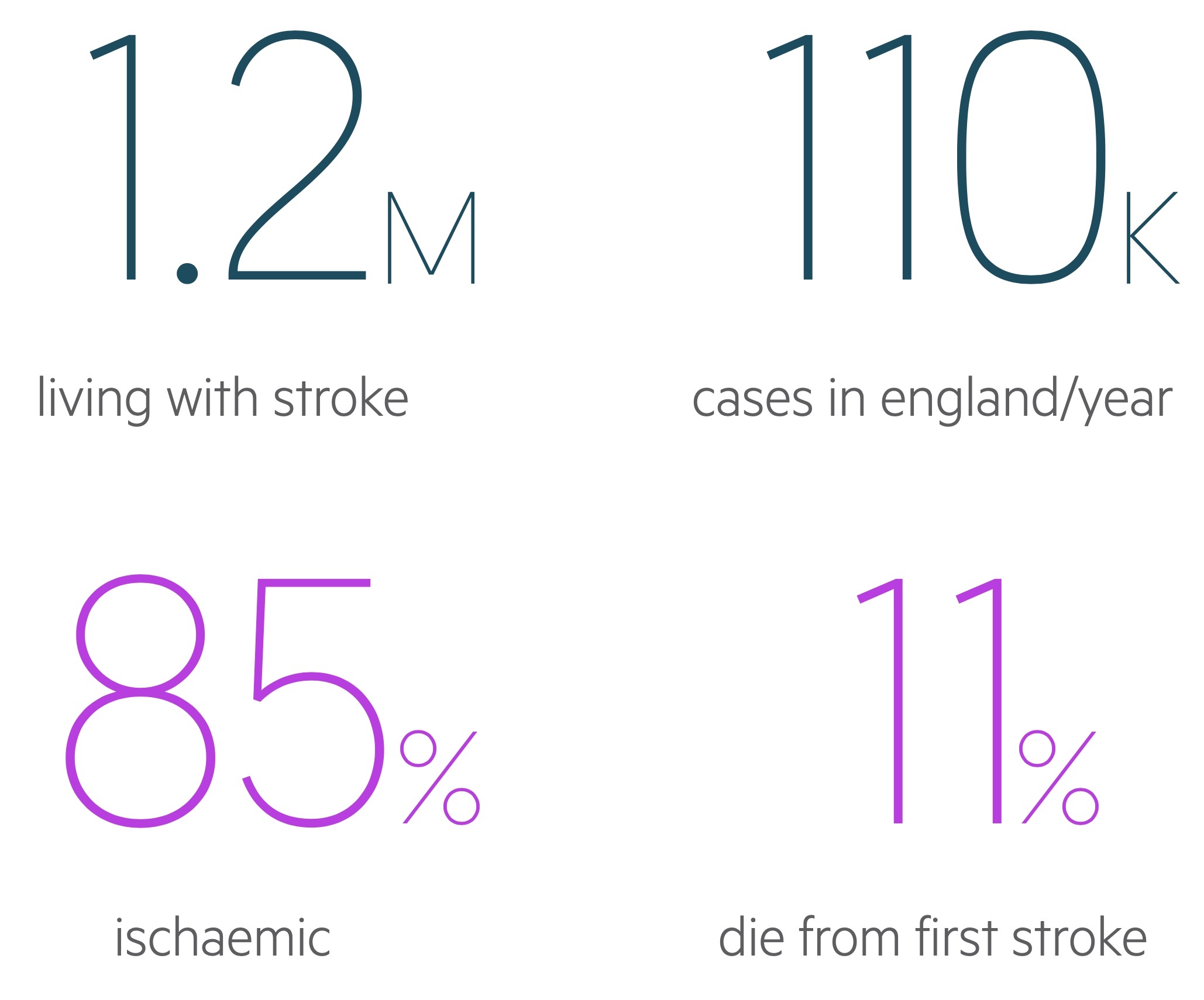

Stroke is a common medical emergency that requires urgent recognition and treatment. The total number of strokes each year is estimated at 110,000 and the mortality from a first-ever stroke is 11%. Strokes can broadly be categorised as:

- Ischaemic: caused by occlusion of blood vessels, most common accounting for 85% of cases.

- Haemorrhagic: result from bleeding, accounts for 15% of cases.

Stroke is a defined as a clinical syndrome characterised by sudden onset of rapidly developing focal or global neurological disturbance, which lasts more than 24 hours or leads to death. This traditional 'time-based' definition of 24 hours is largely outdated. This is because significant neurological injury can occur within a much shorter time window.

We now define an ischaemic stroke (most common) as an episode of neurological dysfunction caused by focal cerebral, spinal or retinal infarction. Infarction being tissue death due to ischaemia that can be characterised on pathology, imaging or objective clinical evidence. If we could only use objective clinical evidence, then ≥24 hours would be necessary in the definition.

Classification

Strokes can be classified into two major types: haemorrhagic or Ischaemic.

Ischaemic

Ischaemic strokes are due to occlusion of blood vessels that supply the brain parenchyma leading to infarction (tissue necrosis secondary to ischaemia). Ischaemic strokes are common accounting for 85% of all strokes.

Ischaemic strokes are sub-classified according to the Bamford/Oxford classification (discussed below).

Haemorrhagic

Haemorrhagic strokes are the result of bleeding within the brain parenchyma, ventricular system or subarachnoid space. Haemorrhagic strokes account for approximately 15% of all strokes.

They are further divided into an intracerebral haemorrhage (ICH) or subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH). Due to the different presentation and management, SAH is usually discussed separately.

Aetiology & pathophysiology

Bleeding and occlusion represent the final common pathway in stroke development.

Both types of stroke ultimately cause cerebral tissue damage, which is precipitated by one or more underlying conditions.

Ischaemia

Ischaemic strokes are the result of occlusion to cerebral vessels. This can be the result of a thrombus (atheromatous plaque) within a vessel, embolus (blood clot) arising from a distant site, or rarely, dissection.

- Thrombosis: local blockage of a vessel due to atherosclerosis. Precipitated by cardiovascular risk factors (e.g. hypertension, smoking) or small vessel disease (e.g. vasculitis, sickle cell).

- Emboli: propagation of a blood clot that leads to acute obstruction and ischaemia. Typically due to atrial fibrillation or carotid artery disease.

- Dissection: a rare cause of cerebral ischaemia from tearing of the intimal layer of an artery (typically carotid). This leads to an intramural haematoma that compromises cerebral blood flow. May be spontaneous or secondary to trauma.

Haemorrhage

Haemorrhagic strokes are most commonly due to hypertension. Other causes of non-traumatic intracerebral haemorrhage include vascular malformations (e.g. arteriovenous malformation, ateriovenous fistula), brain tumour, vasculitis or bleeding disorders, among others. Trauma is another major cause of intracerebral haemorrhage but is usually classified as part of traumatic brain injuries.

Risk factors

Risk factors for stroke relate to conditions that affect the integrity of vessels or increase the risk of embolisation.

Stroke is a cardiovascular disease, and as such, it shares many common risk factors with other conditions such as ischaemic heart disease and peripheral vascular disease.

- Smoking

- Diabetes mellitus

- Hypertension

- Hypercholesterolaemia

- Obesity

- Atrial fibrillation

- Carotid artery disease

- Age

- Thrombophilic disorders (e.g. antiphospholipid syndrome)

- Sickle cell disease

Cerebral vessels

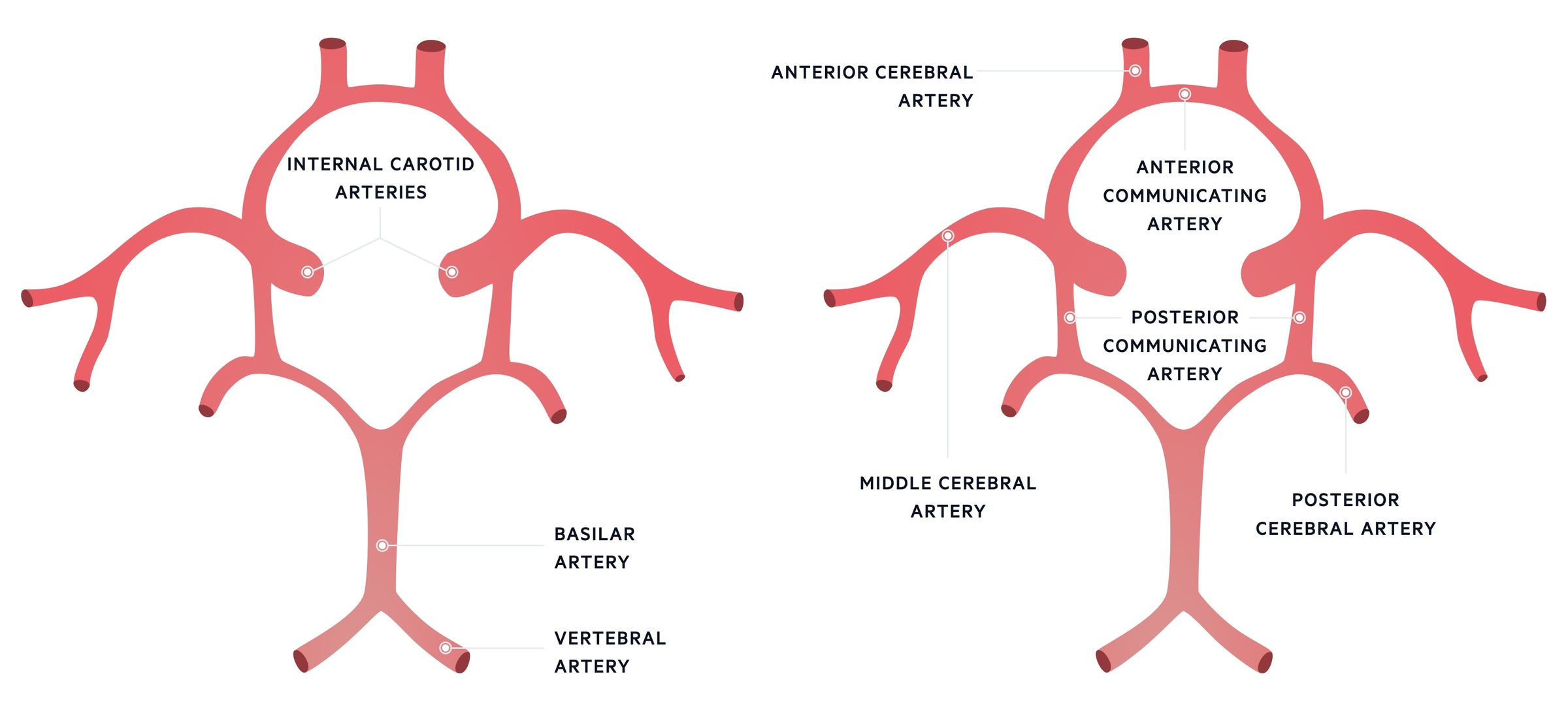

The network of blood vessels that supply the brain are joined by the circle of Willis.

Many blood vessels supply different areas of the brain. These are broadly divided into the anterior and posterior circulation.

- Anterior circulation: a network of blood vessels arising from the carotid arteries.

- Posterior circulation: a network of blood vessels arising from the vertebrobasilar arteries.

Individual blood vessels correspond to areas of the brain that have specific motor, sensory, and/or high cortical functioning (e.g. speech).

Cerebral arteries

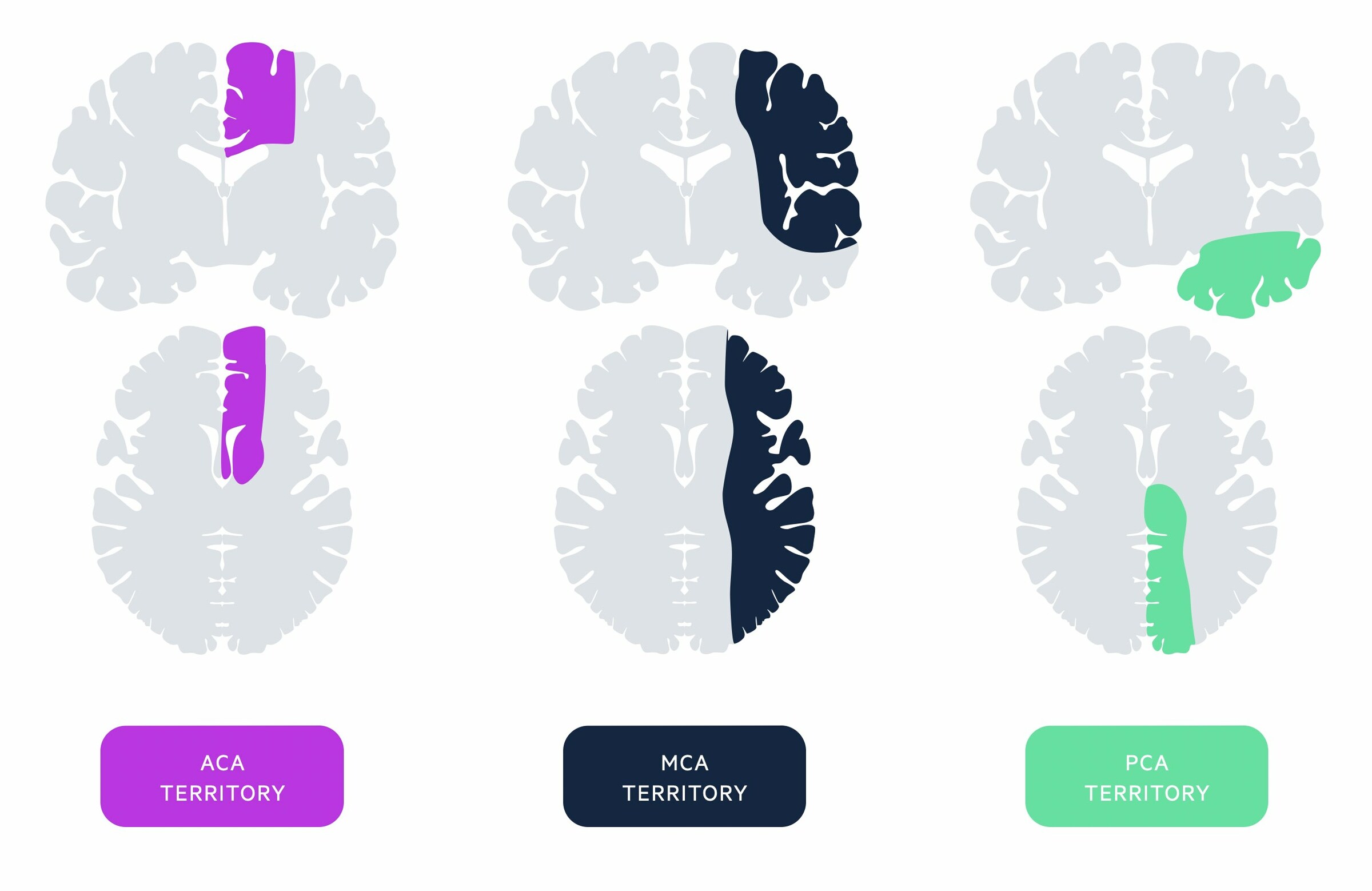

There are three major cerebral vessels, which are connected by communicating arteries at the circle of Willis.

- Anterior cerebral artery: supplies part of the frontal and parietal lobe. Part of the anterior circulation of the brain

- Middle cerebral artery: supplies a large proportion of the lateral surface of each brain hemisphere including the internal capsule and basal ganglia. Most common site of infarction. Forms part of the anterior circulation of the brain

- Posterior cerebral artery: supplies the occipital lobe and inferior proportion of the temporal lobe as well as some deep structures (e.g. thalamus). Forms part of the posterior circulation of the brain

Occlusion of these arteries leads to a characteristic set of clinical features corresponding to the motor and/or sensory functions they help control.

Circle of Willis

The circle of Willis is an arterial polygon and is the main arterial blood supply to the brain. It connects the anterior and posterior cerebral circulation, which arise from the carotid and vertebrobasilar systems, respectively.

- Carotid system: the common carotid artery gives off the internal and external carotid arteries. The internal carotid artery is vital to the circle of Willis. It gives off the anterior and middle cerebral arteries as well as the posterior communicating artery.

- Vertebrobasilar system: the two vertebral arteries join to form the basilar artery. Multiple branches arise from this artery. The basilar artery gives off the posterior cerebral arteries and joins anterior circulation via the posterior communicating artery.

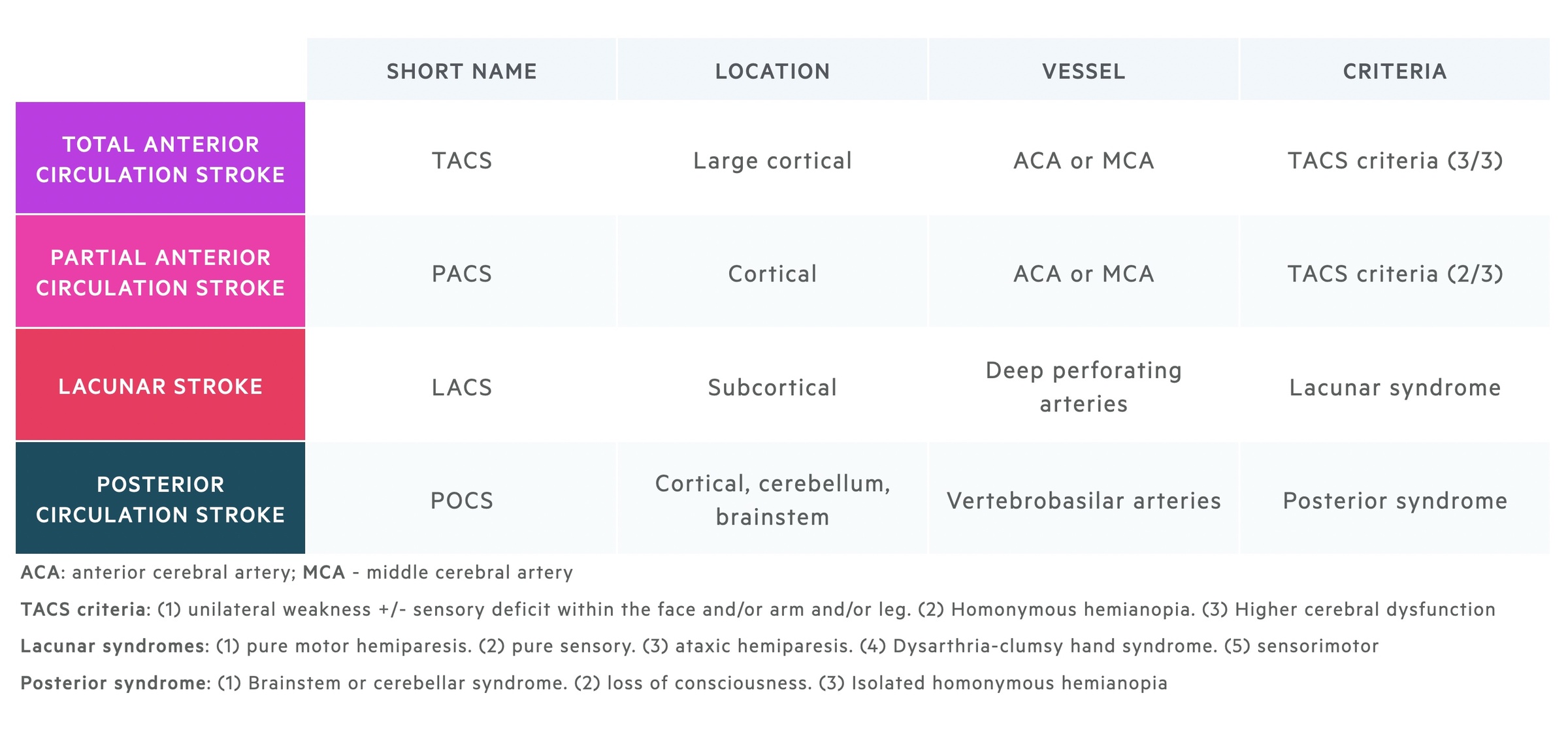

Bamford/Oxford classification

The Bamford/Oxford classification is used to subclassify ischaemic strokes.

This system differentiates ischaemic strokes based on the presenting clinical features, which correlates with the cerebral territory affected.

Clinical features

A stroke presents with sudden, focal neurological deficit that reflects the area of brain devoid of blood flow.

Haemorrhagic

Patients with a haemorrhagic stroke are more likely to present with global features such as headache and altered mental status.

- Headache

- Altered mental status

- Nausea & Vomiting

- Hypertension

- Seizures

- Focal neurological deficits (dependent on location of bleed)

Anterior ischaemic stroke

Patients with anterior ischaemic strokes (i.e. TACS, PACS, LACS) develop a constellation of features dependent on the extent and location of the infarct.

- Unilateral weakness and/or sensory deficit: face and/or arms and/or legs

- Homonymous hemianopia: visual field loss on the same side of both eyes

- Higher cerebral dysfunction: dysphasia, visuospatial dysfunction (e.g. neglect, agnosia)

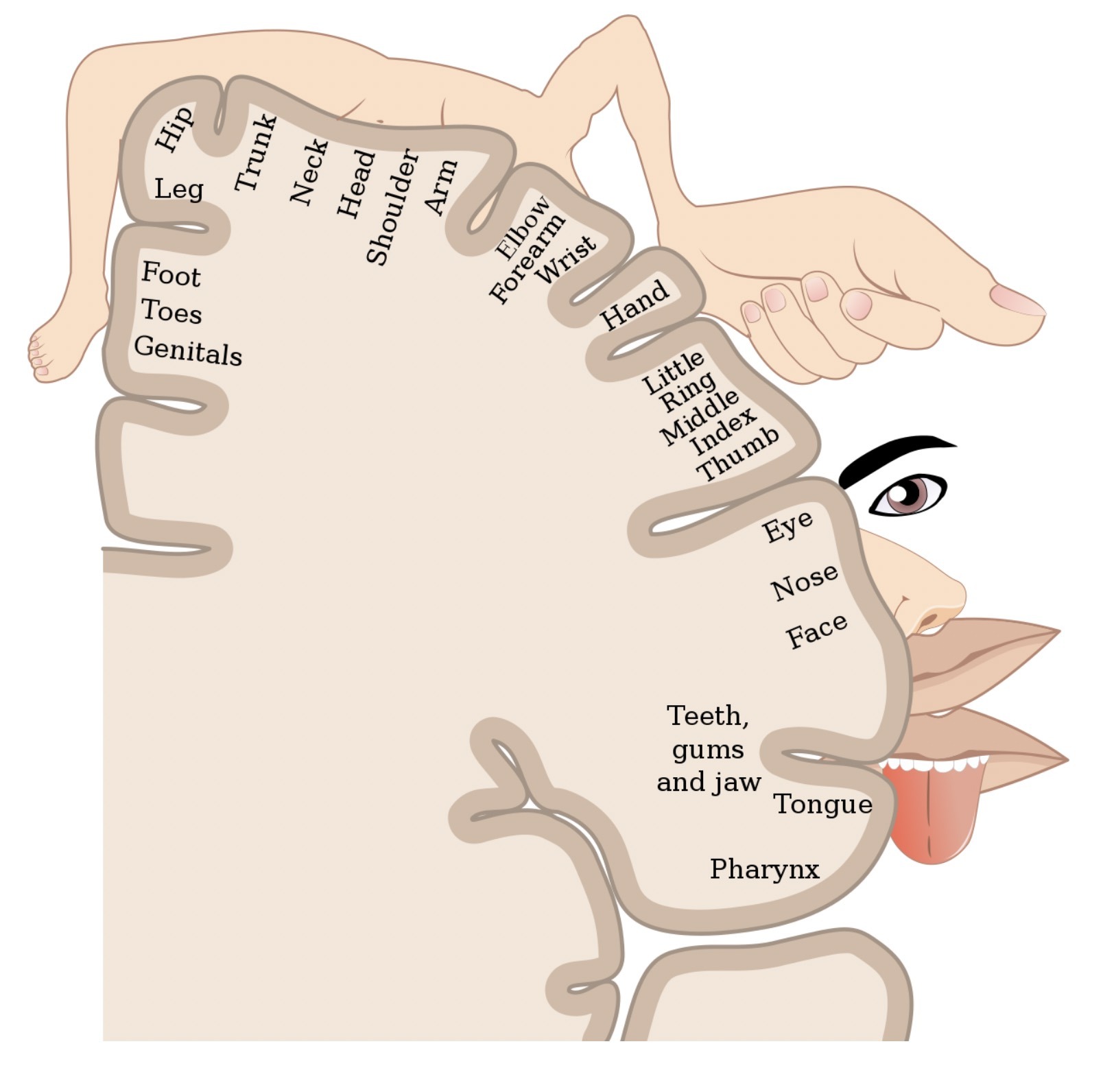

Classically, an isolated infarction of the anterior cerebral artery leads to contralateral leg weakness only. This is because individual areas of the motor and sensory cortex that control movement and sensation, respectively, correspond to specific areas of the body. This 'biological map' is often referred to as the 'cortical homunculus' (homunculus refers to 'little man' in Latin). The anterior cerebral artery supplies an area of the motor cortex that controls leg movement. We can see this clearly in the diagram below.

The cortical homunculus - areas of the body that correspond to the motor and sensory cortex

Image courtesy of Popadius. Wikimedia commons.

Posterior ischaemic stroke

The posterior circulation is composed of the vertebrobasilar arterial system. This supplies the brainstem, cerebellum and occipital cortex. Therefore, posterior strokes can affect balance, vision, and cranial nerves. POCS account for 20-25% of ischaemic strokes.

- Dizziness

- Diplopia

- Dysarthria & Dysphagia

- Ataxia

- Visual Field defects

- Brainstem syndromes: often seen with crossed signs*

*ipsilateral cranial nerve lesions with contralateral sensory and motor limb deficits. This is because many tracts (e.g. corticospinal tracts) cross over at the brainstem (i.e. information from the right hemisphere crosses over to provide infromation to the left side of the body). This is known as decussation.

Posterior stroke syndromes

A collection of syndromes that occur due to infarction of specific posterior circulation arteries.

Commonly referred to as ‘brainstem syndromes’. Classical examples include ‘Wallenberg syndrome’ (posterior inferior cerebellar artery occlusion) or ‘locked-in syndrome’ (basilar artery occlusion).

Wallenberg syndrome, also known as lateral medullary syndrome due to its location, presents with a constellation of features:

- Nystagmus

- Vertigo

- Ipsilateral Horner’s syndrome

- Ipsilateral facial sensory loss

- Dysarthria & dysphagia

- Diplopia

- Contralateral pain and temperature loss

Diagnosis

Any patient with a suspected stroke on clinical assessment should be referred urgently to a stroke unit.

Stroke is initially a clinical diagnosis based on the history and examination. The ‘FAST test’ is used in the community to quickly screen patients who require urgent transfer to a hyperacute stroke unit (HASU).

In hospital, patients are assessed using the NIHSS score (see below) in correlation with urgent cross-sectional imaging (i.e. CT head +/- CT angiography). Patients outside the thrombolysis/thrombectomy window may be assessed locally, as appropriate, before transfer to a stroke centre.

Clinical assessment in suspected stroke:

- Onset & duration of symptoms: collateral history may be needed

- Associated symptoms: headache, vomiting, syncope, seizures (if witnessed)

- Neurological deficit: see clinical features

- Cardiovascular risk factors: hypertension, diabetes, smoking, high cholesterol, family history

- Co-morbidities: heart disease, atrial fibrillation, carotid disease, previous stroke/TIA

- Anticoagulation history

- Contraindications to thrombolysis or thrombectomy

The Face Arm Speech Time test (FAST test)

A rapid diagnostic screen to assess for features of TIA/stroke used in the community. Anyone with a positive screen should be assessed urgently at a stroke unit. The test is positive if any of the following are met:

- New facial weakness

- New arm weakness

- New speech difficulty

Differential diagnosis

Numerous conditions can present similarly to stroke, which are collectively referred to as ‘stroke mimics’.

- Toxic/metabolic: hypoglycaemia, drug and alcohol consumption

- Neurological: seizure, migraine, Bell’s palsy

- Space occupying lesion: tumour, haematoma

- Infection: meningitis/encephalitis, systemic infection with ‘decompensation’ of old stroke

- Syncope: extremely uncommon presentation of TIA, many other causes

- Non-organic: functional neurological disorders (FND)

NIHSS score

The NIH Stroke Scale (NIHSS) is a scoring system out of 42, which has been designed as a predictive score of clinical outcome in stroke.

This scoring system is completed on initial assessment of a patient with suspected stroke. It is important for the consideration of thrombolysis and clinical outcome.

A score < 4 is associated with a good clinical outcome. A high score (> 22) indicates a significant proportion of the brain is affected by ischaemia, and as such, there is higher risk of cerebral haemorrhage with thrombolysis. A score ≥ 26 is often considered a contraindication to thrombolysis.

Investigations

CT head is the key investigation in patients presenting with a suspected stroke.

A CT head is very sensitive for detecting cerebral haemorrhage. In an ischaemic stroke, CT imaging is often normal in the first few hours. Therefore, a normal CT head in the presence of neurological symptoms is presumed secondary to ischaemia.

- Bedside: observations, blood glucose, ECG (AF)

- Bloods: FBC, U&Es, Bone profile, LFT, ESR, coagulation, lipid profile, HbA1c

- Imaging: CT head +/- CT angiography +/- MRI head

- Special: Echocardiography, carotid dopplers, 24 hour tape, young stroke screen

Acute management

Thrombolysis and thrombectomy have revolutionised the management of stroke.

The first step in acute management is to determine whether the stroke is haemorrhagic or ischaemic on the initial CT.

Haemorrhagic stroke

Management depends on the extent of bleeding and the suitability for neurosurgical interventions (e.g. co-morbidities, frailty). In most small bleeds, there is no requirement for neurosurgical intervention.

Neurosurgical intervention may be required for larger bleeds with significant neurological deterioration. This includes use of decompressive hemicraniectomy in those meeting specific clinical criteria or suboccipital craniotomy for posterior fossa bleeds.

Ischaemic stroke

If the CT head does not reveal any signs of intracerebral bleeding then the patient is managed as an ischaemic stroke. An initial decision is made about suitability of thrombolysis based on stroke severity, contraindications and timeframe.

- Thrombolysis: synthetic tissue plasminogen activator (e.g. Alteplase). 'Clot-busting' drug

- Contraindications: checklist (e.g. neurosurgery last 3 months, active internal bleeding, etc)

- NIH stroke scale: consider if score ≥ 5 and < 26

- Timeframe: within 4.5 hours (‘thrombolysis window’). Limited benefit beyond this time with increased bleeding risk

If thrombolysis is not appropriate, patients should be started immediately on 300 mg of aspirin for two weeks. After two weeks, conversion to secondary prophylaxis with 75 mg clopidogrel is indicated unless anti-coagulation (e.g. NOAC) is appropriate because of aetiology (e.g. AF). If thrombolysis was given, aspirin is usually started 24-48 hours following treatment.

Thrombectomy

Thrombectomy involves removal of thrombus from a vessel. Mechanical thrombectomy can be completed in specialist centres by the interventional neuroradiology team with the use of special clot retrieval systems. It can be combined with thrombolysis (if not contraindicated and within the licensed time window).

Use requires specific criteria set out by NICE. These are location specific (anterior versus posterior stroke) and dependent on potential to salvage brain tissue according to CT perfusion or diffusion-weighted MRI.

Ongoing management

Admission to a hyperacute stroke unit for ongoing monitoring is essential.

Secondary prevention and rehabilitation, with involvement of the full multidisciplinary team (MDT), forms the cornerstone of stroke management.

- Blood pressure control: acute control with haemorrhage or peri-thrombolysis. Subsequent treatment if hypertensive emergency, otherwise gradual and cautious introduction of agents.

- Blood glucose control: maintain glucose between 4-11 mmol/L. Optimise diabetic control

- Anti-lipid therapy: commence on statin 48 hours after the initiation of a stroke unless already established. Avoided in cerebral haemorrhage.

- Anti-platelet/anti-coagulation: two weeks of aspirin 300 mg followed by clopidogrel 75 mg daily. Warfarin/direct-acting oral anticoagulant may be appropriate (e.g. AF)

- Carotid artery assessment: carotid dopplers or CT angiography. Consider carotid endarterectomy if anterior stroke and significant stenosis (ECST - 70-99% / NASCET - 50-99%).

- Swallow and nutrition assessment: complete on all patients. Nil by mouth if unsafe swallow and consider nasogastric tube within 24 hours. SALT/dietician input essential.

- Rehabilitation: referral to local stroke unit. All members of MDT essential (PT, OT, SALT, dieticians, social worker, stroke coordinator, neuropsychologist).

- Palliative care: early recognition and referral in those with suspected poor outcome.

Complications

Complications from stroke are broadly divided into early and late.

Early

- Haemorrhagic transformation of ischaemic stroke

- Cerebral oedema

- Seizures

- Infection (e.g. aspiration pneumonia)

- Cardiac arrhythmias

- Venous thromboembolism

- Death

Late

- Mobility & sensory issues

- Bladder & bowel dysfunction

- Pain

- Fatigue

- Cognitive problems

- Visual problems

- Emotional and psychological issues

- Issues with swallowing, hydration and nutrition

Malignant MCA infarction

Term used to describe rapid neurological deterioration due to cerebral oedema following middle cerebral artery (MCA) territory stroke. May require urgent decompressive hemicraniectomy in selected cases.

Driving

It is vital to advise all patients who have had a stroke to stop driving.

Patients should always be advised to check the DVLA for the most up to date recommendations on driving.

- Cars and motorcycles: stop driving one month. Inform DVLA if ongoing symptoms after one month

- Larger vehicles (e.g. buses, lorries): stop driving, inform the DVLA

Prognosis

Stroke is the 4th leading cause of mortality in the UK.

In the UK the prognosis following stroke has improved dramatically over the past several decades. Improved public awareness, protocolled management and hyper-acute stroke units have all contributed to a 46% reduction from 1990 to 2010.

- Mortality: One in seven patients with acute stroke die in hospital. Mortality following a haemorrhagic stroke is 35-40% higher than ischaemic stroke.

- Disability: Around 40% will have difficulty with basic activities of daily living 6 months following their stroke.

Last updated: October 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback