Systemic lupus erythematosus

Notes

Overview

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a multi-system, inflammatory, autoimmune disorder.

SLE, also shortened to lupus, is a multi-system condition and therefore may present in a myriad of ways. Typical manifestations include characteristic skin rashes, arthralgia and renal impairment.

Management is complex but involves symptomatic relief, immunosuppressive agents and more novel biologics.

Epidemiology

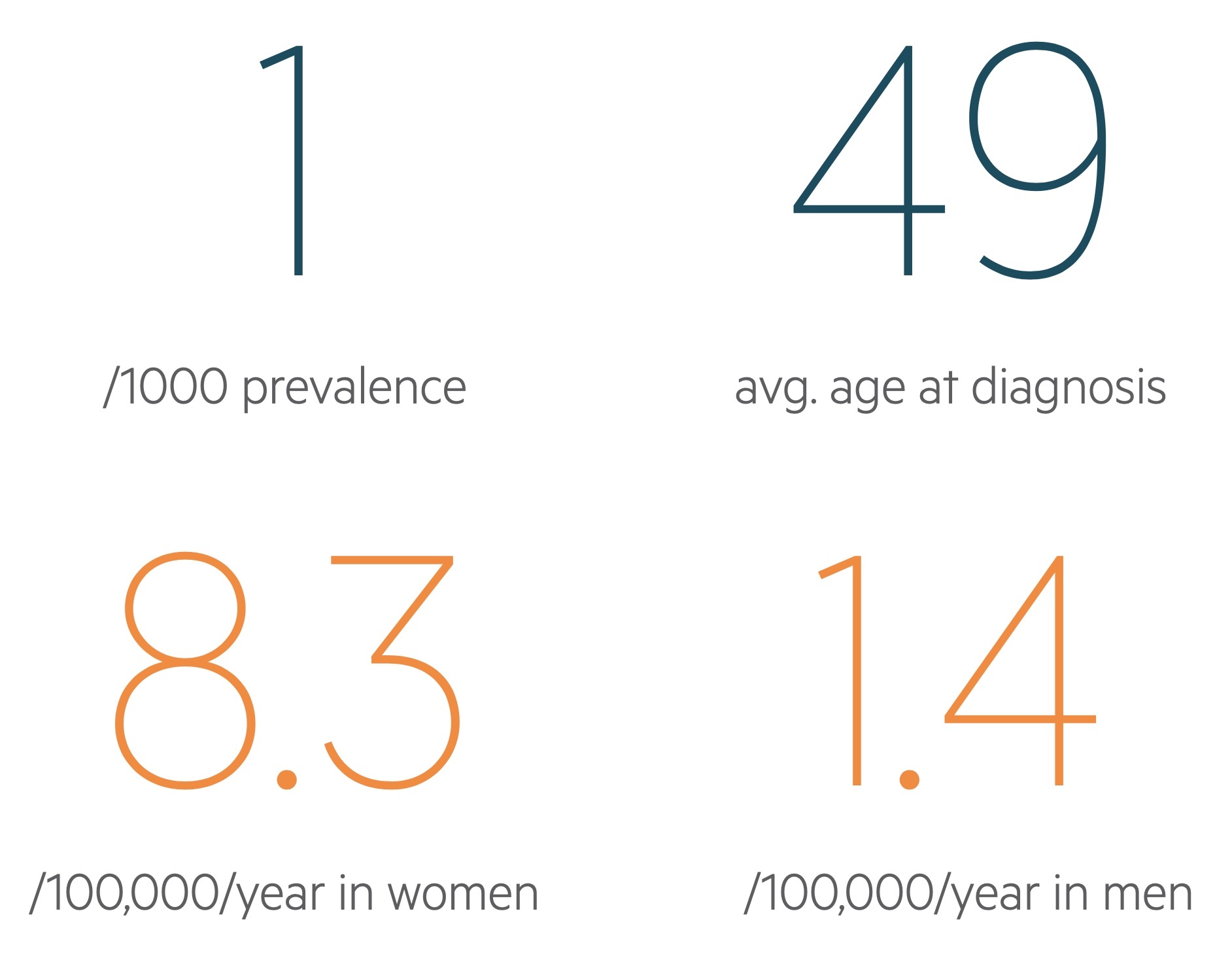

SLE is thought to affect almost 1 in 1000 individuals in the UK.

It often presents in women of reproductive age, with an average age at diagnosis of 48.9, but can manifest at any age. The condition is more common in women and those of Afro-Caribbean or South Asian descent.

The gender imbalance depends on age, but is greatest during reproductive years when SLE is 7-15 times more common in women than men.

Aetiology

The aetiology of SLE appears to be an interplay of genetic, hormonal and environmental factors.

SLE is a complex condition with an aetiology that is not completely understood. Here we discuss some of the most important and well characterised aetiological factors.

Genetics

Genetics play a major role in the development of SLE. Monozygotic twins have high concordance, estimated to be around 25% whilst dizygotic twins have concordance of just 3%. Genome studies have identified numerous genes that may influence the chance of developing SLE. As may be expected, affected sites include the HLA region on chromosome 6 and genes encoding for immune cells.

Hormones

Premenopausal women are most commonly affected and it is thought the sex hormones play an important aetiological role. There has been some evidence indicating those with early menarche or on oestrogen containing therapies have an increased risk of developing SLE.

Drugs

A numbers of medications including hydralazine, isoniazid and penicillamine have been shown to trigger a form of SLE.

Viral factors

Viruses have been implicated as triggers for SLE. In particular there is suspicion infection with Epstein-Barr virus may be involved.

Pathophysiology

SLE is an autoimmune condition characterised by loss of tolerance to self-antigens.

It has been proposed that SLE may arise from exposure of the immune system to blebs, cellular remnants, from apoptotic cells. These blebs which feature self-antigens are not efficiently removed and are carried to lymphoid tissue.

An immune response is raised when these are taken up by antigen-presenting cells and presented to T-lymphocytes resulting in B-lymphocyte activation and autoantibody production.

The failure to inactivate lymphocytes responding to self-antigens leads to circulating autoantibodies and immune mediated damage to ones own cells.

Clinical manifestations

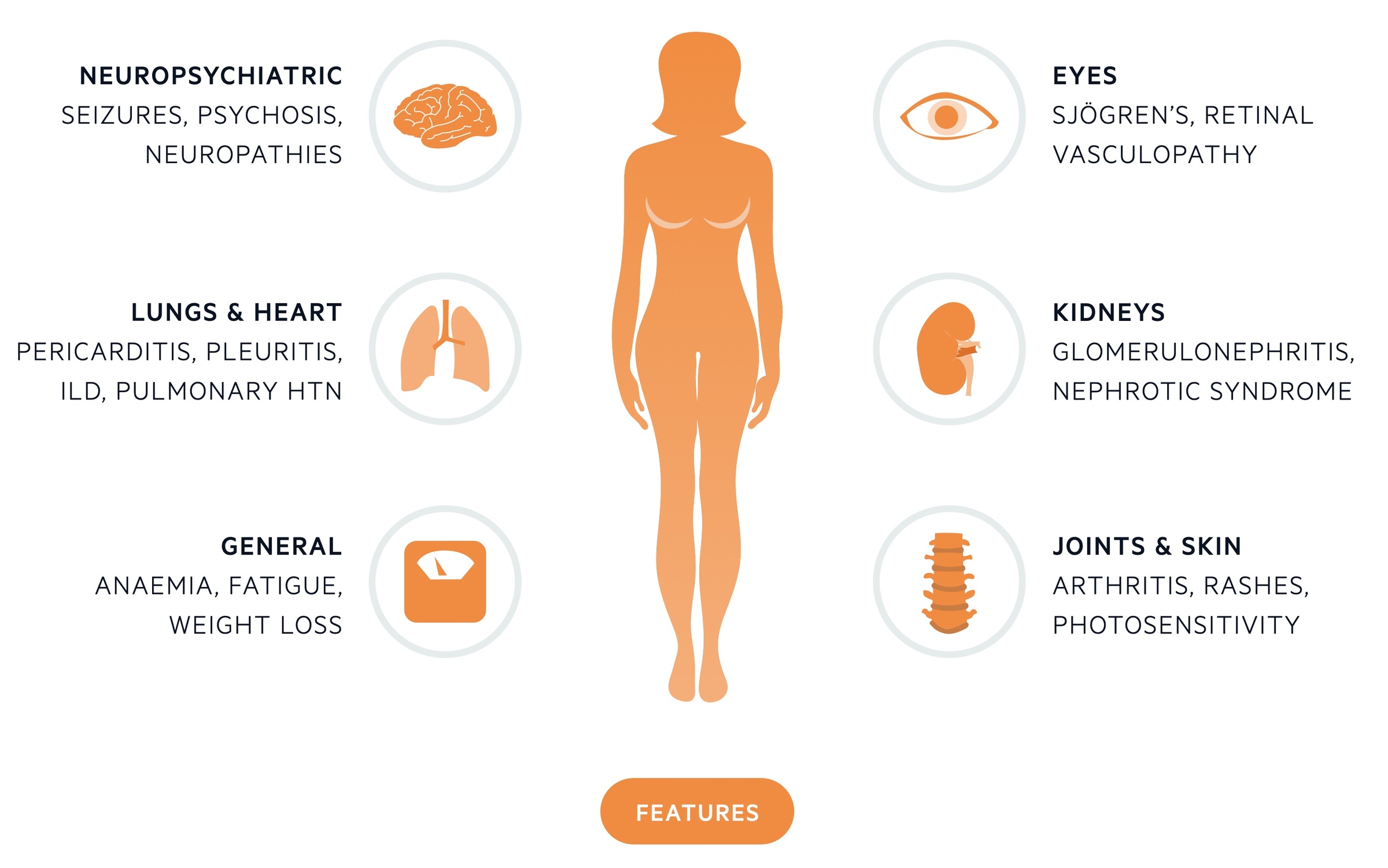

SLE is a multi-system disorder that may present with non-specific constitutional symptoms, arthritis, skin rashes or evidence of organ dysfunction.

Presentation varies widely between patients. Often patients present with some-what non-specific constitutional symptoms accompanied by arthritis/arthralgia. Clinicians need a high index of suspicion to avoid missing cases.

General features

Non-specific symptoms like fatigue and malaise are common as is weight loss prior to diagnosis. Fever may be seen and myalgia is frequently experienced.

Joints

Arthritis is the most common clinical manifestation of SLE affecting up to 90% of patients. There are a number of patterns:

- Symmetrical small joint polyarticular arthritis (most common form)

- Jaccoud arthropathy (rare)

- Avascular necrosis (rare)

Skin

Involvement of the skin is seen in around 85% of cases. Numerous different manifestations may be seen. The butterfly (malar) rash is characteristic rash of SLE - an erythematous rash that lies on the cheeks and across the bridge of the nose. Photosensitivity is common and alopecia may occur.

NOTE: Discoid lupus refers to a benign version of SLE confined to the skin.

Kidneys

Nephritis is seen in 25-50% of patients. Various forms of glomerulonephritis may be seen and all patients with SLE should have regular screening for haematuria, proteinuria and evidence of renal impairment.

Lungs

There are many pulmonary manifestations of SLE, which affect up to 50% of patients, including:

- Pleurisy

- Pneumonitis

- Pleural effusions

- Pulmonary fibrosis

Cardiovascular

The most common cardiac manifestation of SLE is pericarditis. Disease may also effect the myocardium, valves, coronary vessels and conduction system. Less common manifestations include:

- Libman-Sacks endocarditis

- Myocarditis

- Heart block

Vasculitis may be seen in SLE and can affect vessels of all sizes.

Neuropsychiatric

Fluctuating cognitive dysfunction is relatively common in patients with SLE. Some are affected by seizures, ataxia and psychosis. Polyneuropathy and cranial nerve lesions may be seen.

Other

- Eyes: Sjogren’s syndrome is seen in around 15% of patients.

- Gastrointestinal: Many manifestations from mouth ulcers to mesenteric vasculitis. Lupus hepatitis and acute pancreatitis may also occur.

- Haematology: Anaemia of chronic disease is common, leucopenia and thrombocytopenia may also be seen.

Though not technically a manifestation patients with SLE have been noted to have an increased risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Investigation and diagnosis

The diagnosis of SLE relies on suggestive clinical features or organ involvement and the presence of characteristic immunological findings.

The diagnosis of SLE can at times be challenging. This is reflected by the multiple diagnostic criteria that have been developed. These include:

- EULAR/ACR (2019): Positive ANA is required, then there are ten criteria (clinical and immunological) with patient said to have SLE if they score 10 or more points.

- SLICC (2012): Patients meet 4 of 17 criteria with a requirement that one comes from the clinical criteria and one from the immunological criteria.

Diagnosis is not mandated by these criteria but they can be useful definitions to enable comparative research.

Bedside

- Vital signs

- Blood sugar

- ECG

Bloods

- FBC

- Renal function

- Clotting screen

- LFT

- ESR/CRP

- Creatine kinase

- Vitamin D3

- Thyroid profile

Immunology

- Antinuclear antibody (ANA): Positive in about 95% of patients with SLE, however it is non-specific and may be seen in other conditions or entirely well patients.

- C3/C4 level: Low levels are seen in SLE.

- Anti-dsDNA and anti-Smith antibodies: The presence of these antibodies is specific for SLE and highly predictive.

- Antiphospholipid antibodies (lupus anticoagulant, anti-cardiolipin antibodies, anti-beta2-glycoptrotein-1): It is advised antiphospholipid antibodies are ordered in all patients at time of diagnosis particularly if past history of miscarriages or venous thromboembolism.

- Anti-Ro/La and anti-RNP antibodies: Relatively poor sensitivity and non-specific with Anti-Ro/La seen in Sjogren’s.

- Direct Coombs test: Assess for evidence of haemolytic anaemia.

- Immunoglobulins

Urine

- Urinalysis

- Random protein:creatinine ratio / 24-hr urine collection for protein

Imaging

- Chest X-ray: Helps to identify cardiac/respiratory complications.

- MSK X-rays: May be ordered of the relevant joint in patients presenting with arthropathy.

- Renal USS: In patients with suspected lupus nephritis or as part of an AKI screen to exclude other causes.

- CT chest: To evaluate the lungs in patients presenting with features suggesting involvement.

- CT/MRI brain: May be ordered in patients presenting with neurological signs.

- Echocardiogram: May be used in patients with suspected pericardial or valvular involvement.

Biopsy

Skin: Immunofluorescence shows immune deposits at the dermal-epidermal boundary. Of use in patients with skin lesions and diagnostic uncertainty.

Kidney: An invasive investigation that is not without complication (e.g. infection, bleeding). Highly sensitive and specific for lupus nephritis though it use as an investigation should be at the discretion of a nephrologist.

Drug-induced lupus

Certain medications may trigger an autoimmune response that leads to a clinical syndrome similar to SLE.

Drug-induced lupus refers to a specific clinical syndrome whereby a medication causes an SLE-like illness. It has very similar clinical manifestations to idiopathic SLE, but there are some clinical and immunological features that differ between the two conditions.

Common drugs

There are a variety of medications that have been implicated in drug-induced lupus. The risk of developing drug-induced lupus can be divided based on risk from high to very low.

- High (> 5%): Procainamide, hydralazine

- Moderate (1-5%): Quinidine

- Low (0.1-1%): Penicillamine, carbamazepine, methyldopa, minocycline

- Very low (< 0.1%): multiple agents

Clinical features

The clinical spectrum of drug-induced lupus is highly variable. Patients will usually have features of fever, arthralgia/arthritis, myalgia, rash, and/or serositis. Severe internal organ involvement is uncommon. Additionally, cutaneous involvement is far less common in drug-induced lupus compared to idiopathic SLE. Symptoms most commonly start months to years after exposure to the culprit medication, but can be more abrupt.

Investigations and management

Patients require formal assessment and a series of investigations similar to idiopathic SLE. This is to enable to diagnosis, assess for extent of involvement and determine the severity. One of the hallmarks of drug-induced lupus is the presence of anti-histone autoantibodies, which are found in >95% of cases (formation is drug-specific). Anti-dsDNA, which is highly specific for idiopathic SLE, is uncommon in the drug-induced form.

Management usually involves stopping the culprit medication and managing symptoms with analgesia (e.g. NSAIDs), or in more severe cases, corticosteroids/hydroxychloroquine. Overall, the prognosis is good, but resolution of symptoms may take weeks to months.

Management

SLE is a heterogenous condition and management must be based around individuals.

Consider each patients disease pattern, experiences, co-morbidities and personal priorities. Patient education is a key component and helps to empower patients to take a central role in their disease and its management.

Lifestyle and modifiable risk factors

An active and healthy lifestyle based upon a balanced diet. In patients with existing (or whom develop) co-morbidities such as hypertension or diabetes arrange regular reviews and optimisation of their management.

Smoking is of course an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease and numerous malignancies (amongst other conditions). Additional smoking is known to exacerbate aspects of SLE (renal and skin disease), and adds to the existing increased risk of cardiovascular disease.

Excessive sun exposure should be avoided and use of SPF advised.

Principles of management

The management of SLE is enormously complex and can involve a number of immunosuppressants. The treatment regimens often follow a pattern of induction and maintenance:

- Induction therapy: Aggressive therapy aimed at halting disease progression and inducing remission. Prednisolone and hydroxychloroquine commonly used with a combination of other immunosuppressants depending on severity.

- Maintenance therapy: Less intensive therapy aimed at preventing relapse, again may be made up of a combination of immunosuppressants. Once stable remission is achieved these can be reduced and stopped, typically with hydroxychloroquine continuing.

Here we give a basic overview of the management options. For those interested in more detail and a description of mild, moderate and severe see The British Society for Rheumatology guideline for the management of systemic lupus erythematosus in adults. The management of lupus nephritis is considered separately and is not covered here.

Mild SLE

Typical manifestations of mild SLE include 'fatigue, malar rash, diffuse alopecia, mouth ulcers, arthralgia, myalgia, platelets 50–149 × 109/L'.

In patients with mild SLE treatments include hydroxychloroquine and prednisolone (oral/topical). Methotrexate may be used as are short courses of NSAIDs (in the absence of contraindications).

Moderate SLE

Typical manifestations of moderate SLE include 'fever, lupus-related rash up to 2/9 body surface area, cutaneous vasculitis, alopecia with scalp inflammation, arthritis, pleurisy, pericarditis, hepatitis, platelets 25–49 × 109/L'.

Those with moderate SLE are more likely to require higher doses of steroids such as prednisolone, hydroxychloroquine is normally used. Additional agents may include methotrexate, azathioprine, mycophenolate and ciclosporin.

In refractory cases the monoclonal antibodies rituximab and belimumab may be used.

Severe SLE

Typical manifestations of severe SLE include 'rash involving >2/9 body surface area, myositis, severe pleurisy and/or pericarditis with effusion, ascites, enteritis, myelopathy, psychosis, acute confusion, optic neuritis, platelets <25 × 109/L'.

Patients with severe SLE - those with organ or life-threatening manifestations require immediate and intensive treatment. Investigations must be ordered to exclude other causes or to understand the nature of the underlying manifestation.

The management of severe SLE depends on the nature of the complication. Immunosuppressive regimens for severe active SLE includes prednisolone, hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate, azathioprine, mycophenolate and ciclosporin. With time medications are reduced and stopped, typically continuing hydroxychloroquine.

IV immunoglobulin and plasmapheresis may be used certain circumstances:

- Refractory cytopaenias

- Thrombotic thrombocytopaenic purpura

- Rapidly deteriorating acute confusional state

- Catastrophic variant of APS

Prognosis

SLE has a varied presentation and clinical course with a wide spectrum of severity.

Historically SLE has had a very poor prognosis with a 5-year survival of just 40% in the 1950’s. With earlier diagnosis and better treatment regimens this has dramatically improved with more recent studies quoting 10-year survival of 92%.

Causes of premature death include active disease, thrombotic complications, infections, cardiovascular disease and treatment complications.

Factors associated with a poorer prognosis include black ethnicity, male sex, lupus nephritis, hypertension and antiphospholipid antibodies / antiphospholipid syndrome.

Last updated: June 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback