Hypercalcaemia

Notes

Overview

Hypercalcaemia is defined as a serum corrected calcium concentration > 2.6 mmol/L.

Hypercalcaemia is a common electrolyte abnormality. It occurs when the serum calcium concentration exceeds the amount by which calcium can be deposited in bone or excreted by the kidneys.

Normal serum calcium levels range from 2.2-2.6 mmol/L.

Corrected calcium levels > 2.6 mmol/L are defined as hypercalcaemia. Depending on the level of serum calcium, hypercalcaemia can be graded:

- Mild: 2.6-3.0 mmol/L

- Moderate: 3.0-3.5 mmol/L

- Severe: > 3.5 mmol/L

The most common causes of hypercalcaemia are Malignant hypercalcaemia and Primary hyperparathyroidism.

Calcium physiology

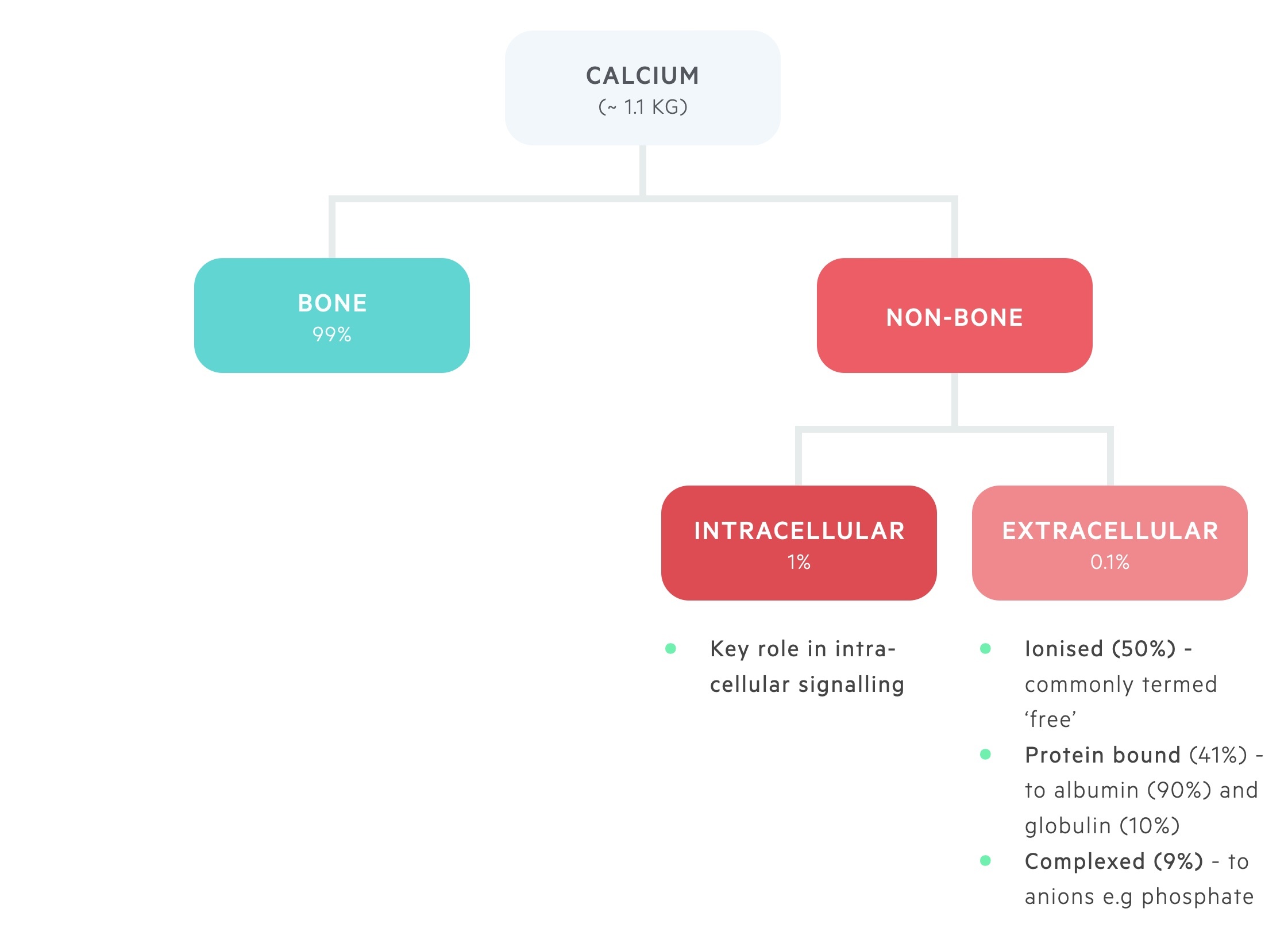

Calcium is distributed between bone and the intra- and extra-cellular compartments.

The majority of body calcium, 99%, is stored in bone.

Approximately 1% of total body calcium is found within the intracellular compartment. Here it plays a key role in intracellular signalling.

Around 0.1% of total body calcium is found within the extracellular pool, this is divided into:

- Ionised (~ 50%) - metabolically active, or ‘ionised’, free pool of calcium.

- Bound (~ 41%) - bound to albumin (90%) and globulin (10%).

- Complexed (~ 9%) - forms complexes with phosphate and citrate.

The balance between stored calcium and the extracellular pool of calcium is a closely regulated process. It is controlled by the interaction of three hormones; parathyroid hormone (PTH), vitamin D and calcitonin.

Decreased extracellular calcium is detected by the calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR) on the parathyroid gland. The parathyroid glands respond to the fall in serum calcium by releasing PTH. PTH stimulates the resorption of calcium from bone, activation of vitamin D (leads to calcium absorption from enterocytes) and increased renal tubular reabsorption of calcium.

Conversely, a rise in extracellular calcium detected by the CaSR has the opposite effect. It leads to a reduction in the release of PTH and stimulates the release of calcitonin. This combined effect helps decrease bone resorption and promotes calcium excretion in the kidneys.

Corrected calcium

Serum calcium levels may be 'corrected' by adjusting them for the albumin level.

As described in the chapter above around 40-45% of extracellular calcium is bound to albumin and around 50% physiologically active and ‘free’ or ionised. Due to calcium binding to albumin, a corrected calcium level is determined by taking into account the albumin level. With modern laboratories, a corrected calcium result is normally automated.

It is estimated that the serum calcium concentration falls by 0.25 mmol/L (0.8 mg/dL) for every 10 g/L (1 g/dL) fall in serum albumin concentration. This can be calculated manually using the following formula:

Corrected calcium (mg/dL) = serum calcium (mg/dL) + 0.8 x (4.0 - serum albumin [g/dL])

Aetiology

Malignancy and primary hyperparathyroidism collectively account for > 90% of cases of hypercalcaemia.

Malignant hypercalcaemia

Malignancy is the most common cause of hypercalcaemia in the inpatient population. Up to 30% of cancers develop hypercalcaemia as part of the natural disease course, a development that is associated with a poor prognosis.

Hypercalcaemia commonly occurs due to release of parathyroid related peptide (PTHrP), which mimics the action of PTH. Other mechanisms include osteolytic damage to bone or activation of vitamin D.

For more information, see our notes on Malignant hypercalcaemia.

Primary hyperparathyroidism

Primary hyperparathyroidism is the most common cause of hypercalcaemia in the general population. It occurs due to excess release of PTH, which leads to bone resorption and excess calcium release. It commonly occurs secondary to a parathyroid adenoma.

Other mechanisms include parathyroid hyperplasia and rarely parathyroid cancer. Primary hyperparathyroidism may be part of a genetic syndrome known as Multiple endocrine neoplasia.

For more information, see our notes on Primary hyperparathyroidism.

Tertiary hyperparathyroidism

Secondary hyperparathyroidism is characterised by excess PTH production secondary to low serum calcium, typically due to chronic kidney disease or vitamin D deficiency.

Tertiary hyperparathyroidism is characterised by autonomous PTH excess due to parathyroid hyperplasia in response to longstanding secondary hyperparathyroidism - seen in patients with chronic kidney disease. Like primary hyperparathyroidism and unlike secondary hyperparathyroidism this is associated with hypercalcaemia.

Thyrotoxicosis

Elevated thyroid hormones can lead to thyroid hormone-mediated bone resorption. Mild hypercalcaemia can be seen in up to 20%.

Hypervitaminosis D

High concentrations of vitamin D lead to hypercalcaemia by increasing calcium absorption and bone resorption. This usually occurs due to inadvertent ingestion of excess amounts of vitamin D or continuing a high loading dose for too long.

Some conditions lead to excess endogenous production of activated vitamin D, which include:

- Granulomatous disorders (e.g. sarcoidosis)

- Cancers (e.g. lymphoma)

Milk alkali syndrome

Milk alkali syndrome is due to the excess ingestion of milk or calcium containing compounds (e.g. calcium carbonate).

The full syndrome is characterised by:

- Hypercalcaemia

- Metabolic alkalosis

- Acute kidney injury

Hypercalcaemia is compounded by metabolic alkalosis, which affects calcium excretion in the distal convoluted tubule of the nephron. In addition, the high calcium levels cause renal vessel vasoconstriction that causes renal impairment and further compounds calcium excretion. Stopping the excess ingestion will lead to improvement in alkalosis and renal function as long as irreversible damage has not occurred.

Other causes

- Chronic lithium use: enhances PTH release

- Thiazide diuretics: lowers urinary calcium excretion

- Adrenal insufficiency: multiple proposed mechanisms

FHH

Familial hypocalciuric hypercalcaemia is a rare autosomal dominant disorder that causes mild hypercalcaemia.

FHH is an autosomal dominant condition caused by a mutation to calcium-sensing receptors (CaSR). CaSRs play an important role in calcium regulation:

- Parathyroid gland: CaSRs enable the parathyroid gland to sense changes to calcium levels and respond appropriately.

- Kidneys: CaSRs have a number of complex functions that appear to increase calcium excretion in the urine when serum levels are raised.

FHH normally causes a mildly elevated calcium with a PTH that is either mildly elevated or at the upper limit of normal. As such it is excellent at biochemically mimicking primary hyperparathyroidism. It can be distinguished by looking for the hypocalciuria that is present in FHH but absent in PHPT.

Clinical features

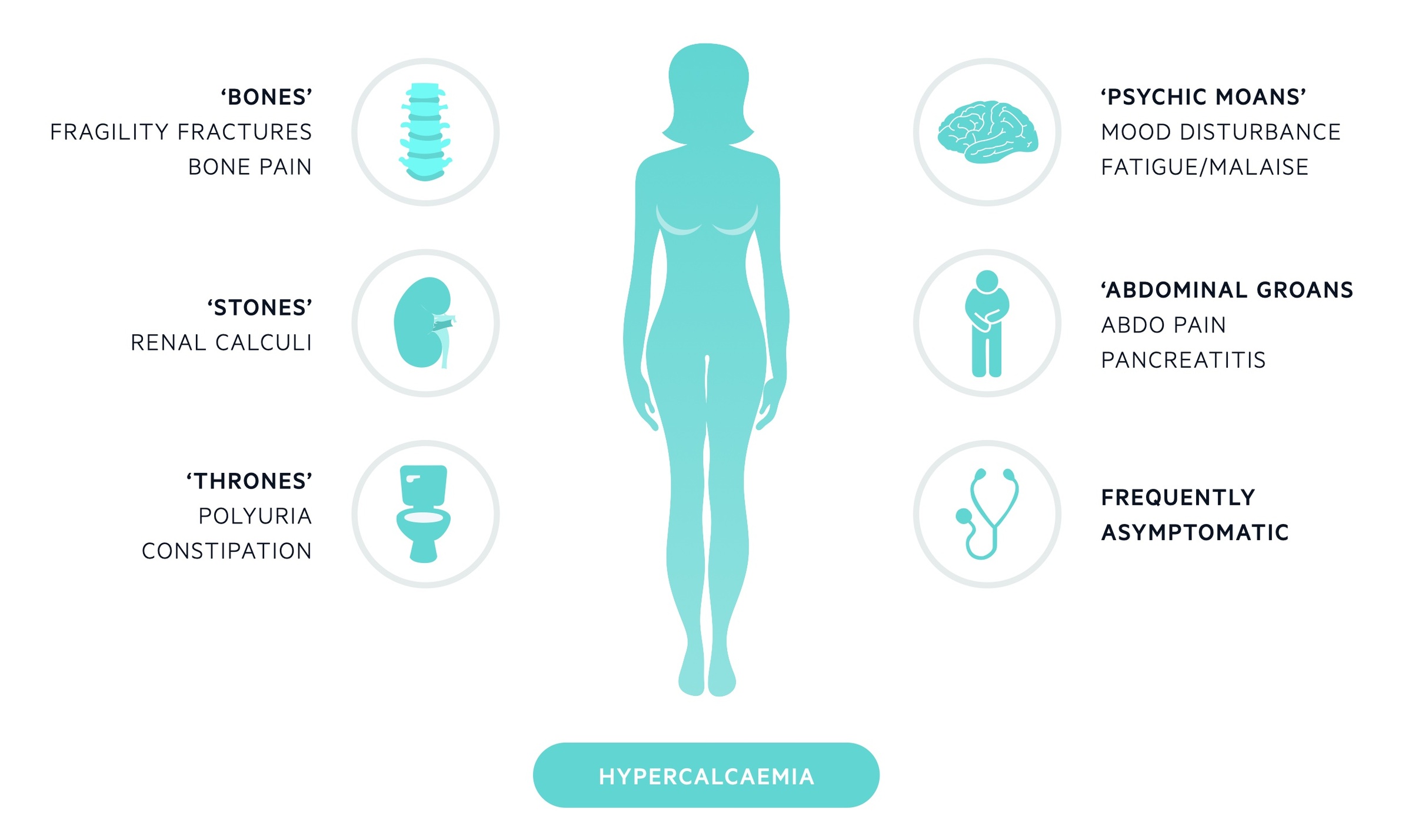

Hypercalcaemia is characterised by renal stones, bone pain, polyuria, abdominal pain and psychiatric features.

Many individuals will be asymptomatic (particularly with primary hyperparathyroidism) and the abnormality is picked up incidentally on routine blood tests. Clinical features, when present, may reflect both the hypercalcaemia and the raised PTH (in cases where this is elevated). In those who are symptomatic the classic phrase ‘bones, stones, thrones, abdominal groans, and psychic moans’ can act as an aide-mémoire.

- Bones - fragility fractures, bone pain

- Stones - renal calculi

- Thrones - polyuria, constipation

- Abdominal groans - abdominal pain, N&V, pancreatitis

- Psychic moans - mood disturbance, depression, fatigue, psychosis

Symptoms, when present, are often vague and non-specific - a high index of suspicion is needed. It is also important to look for signs of the underlying diagnosis. Usually a diagnosis of cancer is previously known but this may be the first presentation.

Patients with longstanding hypercalcaemia may also develop cardiovascular disease with calcium deposits in vessels and on valves and an increased rate of hypertension.

Symptoms

- Fatigue

- Myalgia

- Mood changes

- Depression

- Insomnia

- Polydipsia

- Polyuria

- Constipation

- Fragility fracture

- Renal colic

Signs

- Dehydration (skin turgor, dry mucous membranes)

- Hypertension

- Cardiac arrhythmia (severe disease)

- Confusion (severe disease)

Diagnosis & investigations

The diagnosis of hypercalcaemia is based on a serum corrected calcium > 2.6 mmol/L.

Confirm hypercalcaemia

First confirm hypercalcaemia with a bone profile. Most laboratories will automatically give a corrected calcium result.

Parathyroid hormone

PTH is essential in the work up of hypercalcaemia. It is useful at differentiating between primary hyperparathyroidism and hypercalcaemia of malignancy.

- Elevated PTH (i.e. PTH-mediated): suggestive of primary hyperparathyroidism or tertiary hyperparathyroidism

- Mid-to-upper normal PTH (suspected PTH-mediated): in the context of hypercalcaemia this is considered ‘inappropriately high’ and suggestive of hyperparathyroidism

- Low or low-normal PTH (i.e. non-PTH mediated): suggestive of malignancy, which needs to be excluded. Hypervitaminosis D also possible.

Other investigations

In suspected malignant cases, PTHrP may be requested. Other common investigations include:

- Routine bloods: FBC, U&E, LFT, CRP/ESR

- Thyroid function test

- Vitamin D levels

- ACE (if sarcoid suspected)

- Malignancy screen: protein electrophoresis, serum free light chains, tumour markers

- Urine calcium levels (if FHH suspected)

- General imaging: routine chest x-ray, consider CT chest abdomen pelvis if malignancy suspected

- Parathyroid imaging: used if primary hyperparathyroidism suspected. Neck ultrasound, parathyroid uptake scans (e.g. 99mTc MIBI) and MRI can all be used.

Management

The management of hypercalcaemia depends on the severity and underlying cause.

The principle treatment of symptomatic hypercalcaemia in fluid resuscitation. Those with mild hypercalcaemia may be advised to increase oral intake, whereas those with more severe hypercalcaemia will need admission to hospital for intravenous therapy. Severe hypercalcaemia requiring inpatient management is typically indicative of a malignant cause.

Depending on the underlying cause, definitive management may be possible. In suitable patients parathyroidectomy is curative for primary hyperparathyroidism. See our Primary hyperparathyroidism notes for more detail.

Treatment recommendations

- Mild (< 3 mmol/L) and asymptomatic/mild symptoms: increase oral fluids and avoid precipitants (e.g. thiazide diuretics, lithium, dehydration).

- Moderate (3-3.5 mmol/L): acute rise requires inpatient admission for intravenous fluids. Chronically raised elevations may not require acute management depending on the aetiology and symptomatology.

- Severe (>3.5 mmol/L): all patients require urgent admission to hospital and treatment. Treatment involves aggressive intravenous fluids and consideration of bisphosphonates, particularly if malignancy is suspected.

The management of severe hypercalcaemia initially involves the use of intravenous fluids. This is one of the classic situations when the addition of a loop diuretic (e.g. furosemide) to fluids can be used to enhance urinary calcium excretion.

Bisphosphonates

Bisphosphonates can be considered in severe hypercalcaemia, particularly if malignancy is suspected. They are analogues of inorganic pyrophosphate, which are absorbed onto the surface of the boney network and work by inhibiting the action of osteoclasts.

Unfortunately, they can take several days (2-4) before their action is noticed but they provide calcium-lowering effects over a prolonged period (2-4 weeks). Pamidronate or zoledronic acid are typically used. They are potentially nephrotoxic and contraindicated in severe renal impairment.

An alternative to bisphosphonates is denosumab, which is a monoclonal antibody that binds to RANK ligand and inhibits the action of osteoclasts.

Additional therapies

Other treatment options depend on the suspected underlying cause:

- Corticosteroids: may be used in hypervitaminosis D.

- Surgery: able to provide a cure in primary hyperparathyroidism. Potential option in tertiary hyperparathyroidism

- Cinacalcet: calcimimetic that mimics the action of calcium on calcium-sensing receptors. May be utilised in primary hyperparathyroidism if surgery has failed or not an option. Also used in secondary/tertiary hyperparathyroidism.

- Dialysis: may be reserved for severe, refractory hypercalcaemia.

Last updated: May 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback