Anogenital warts

Notes

Overview

Anogenital warts are caused by human papillomavirus.

Classical anogenital warts cause cauliflower-like lesions known as condylomata, which are typically painless and occur on moist surfaces. They are caused by human papillomavirus (HPV) of which there are > 100 known genotypes.

It is estimated that > 90% of anogenital warts occur secondary to HPV genotypes 6 and 11.

Epidemiology

Anogenital warts are very common, but most infections do not result in visible lesions and self-resolve.

The estimated annual prevalence of anogenital warts is 0.15% in the adult population of the developed world. In the UK, it is estimated that 130,000 cases of anogenital warts are treated in sexual health clinics each year.

Human papillomavirus

There are >100 known genotypes of HPV.

HPV is a non-enveloped DNA virus that is primarily transmitted through sexual contact. Humans are the only known reservoir of the virus. There are over 100 different genotypes of HPV that are identified by numbers (e.g. 4, 37, 18).

Genotypes

The genotype refers to the genetic make-up of the virus. The virus is classified based on molecular analysis because it cannot be grown in vitro and each genotype is assigned a number.

The different genotypes of HPV have high site specificity, meaning they only cause infection in certain areas of skin and mucous membranes. HPV can cause a variety of warty lessons throughout the body.

- Anogenital: almost 40 genotypes have been identified in anogenital warts, but genotypes 6 & 11 account for > 90% of benign lesions. Genotypes 16 and 18 are predominantly responsible for development of anogenital malignancies (e.g. cervical cancer).

- Nongenital (skin): a variety of lesions can develop from various genotypes. Commonly cause flat warts (verrucae planae) and common warts (verrucae vulgaris).

- Nongenital (mucous membrane): causes both benign lesions (e.g. laryngeal or oesophageal papilloma) and malignant lesions (e.g. squamous cell carcinoma of the larynx).

Aetiology & pathophysiology

The majority of anogenital warts are caused by the HPV genotypes 6 and 11.

Anogenital warts are most commonly transmitted through sexual contact. The virus is able to infect epithelial cells by entering through micro-abrasions. Within these cells it proliferates with the use of host cell machinery. Viral DNA from some genotypes can integrate into the host DNA within the nucleus. Certain HPV proteins (e.g. E6 and E6) can inhibit tumour suppressors leading to unregulated cell growth.

Cellular immunity is important in clearance of the virus and the majority of cases do not cause visible lesions and spontaneously resolve within a year. Without clearance, as epidermal cells differentiate and migrate to the surface from the basal layer the virus replicates and matures. As cells desquamate on the surface virus particles are shed to other cells. The replication of the virus within the epidermal cells causes the typical warty appearance of HPV.

The incubation period is usually 3 weeks to 8 months, but it can occur up to 18 months. It is commonly longer in men.

Clinical features

Anogenital warts are benign epithelial skin tumours that typically have a cauliflower-like appearance.

Symptoms

- Asymptomatic

- New growth or lump

- Irritation (locally)

- Bleeding (usually mild)

- Discomfort around lesion

Signs

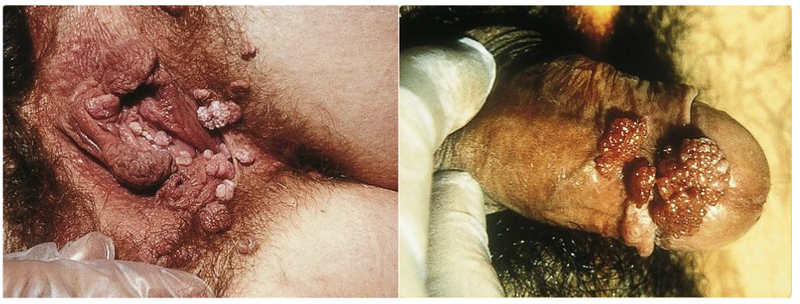

Anogenital warts can differ markedly in size, number and appearance.

- Number: single or multiple lesions

- Consistency: soft and non-keratinised or hard and keratinised

- Base: broad based or pedunculated (i.e. have a stalk)

- Shape: Exophytic (growth outwards) and cauliflower-like (Condylomata acuminata), or flat and plaque-like (Flat condylomata). Rarely, can grow rapidly becoming a large lesion with local tissue infiltration (Buschke-Lowenstein lesion)

Typical anogenital warts located on the vulva (left) and penis (right)

Images courtesy of SOA-AIDS Amsterdam

Sites

- Vagina

- Vaginal introitus

- Cervix

- Labia

- Urethra

- Penile shaft

- Perianal areas

- Anal canal

Intraepithelial neoplastic lesions

Patients infected with genotypes that have malignant potential (e.g. 16 and 18) can present with lesions that have evidence of intraepithelial neoplasia on biopsy/cytology. These areas may be subclinical and only detected on biopsy/cytology.

Intraepithelial neoplasia is a pre-cancerous condition that can be graded according to the extent of dysplasia (abnormal cell growth). A small proportion of these lesions progress to invasive cancer. Detecting cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and the HPV genotypes 16 and 18 forms the basis of cervical cancer screening.

Areas at risk of malignant transformation include:

- VIN: Vulval intraepithelial neoplasia

- VaIN: Vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia

- CIN: Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia

- PAIN: Perianal intraepithelial neoplasia

- AIN: Anal intraepithelial neoplasia

- PIN: Penile intraepithelial neoplasia

These abnormal lesions should be suspected based on the appearance of the lesion, response to treatment, history of intraepithelial neoplasia and immunocompetence.

Diagnosis & investigations

A formal examination is usually enough to make a diagnosis of anogenital warts.

Examination of the anogenital region is usually enough to make a diagnosis of anogenital warts.

- External genitalia examination

- Speculum examination: further examination of the internal genitalia not required if no lesions identified

- Proctoscopy: consider only if anal symptoms or lesions identified at anal margin and cannot visualise upper limit.

- Meatoscopy or urethroscopy: if difficult to visualise intra-meatal warts in men or proximal urethral warts suspected.

Important to record the appearance, site and location of warts, which helps assess response to treatment on follow-up. Acetic acid may be used to aid assessment of lesions.

Atypical lesions (e.g. pigmented, ulcerated or indurated) or those that do not respond to treatment should be biopsied to confirm the diagnosis and assess for malignancy.

Cervical examination

HPV infection with genotypes 16 and 18 is strongly linked with cervical cancer. The UK has a national screening programme for cervical cancer including assessment for these genotypes and CIN.

Other investigations

Patients with suspected anogenital warts should be referred and assessed at a genitourinary medicine (GUM) clinic. This enables a full sexual health screen including assessment for other sexually transmitted infections (e.g. HIV, gonorrhoea, chlamydia, syphilis).

Management

A variety of treatment options are available for anogenital warts.

General advice

Patients should be assessed for other STIs at a GUM clinic and advice given about the condition (e.g. leaflet). Often the psychological distress of the lesions is the worst aspect and patients should be referred for counselling as necessary.

Patients should be advised to use male condoms where necessary because this reduces transmission by 30-60%. They should also be advised to stop smoking as this can affect treatment. Current sexual partners may need assessment for lesions, but contact tracing is not required.

Follow-up should be arranged to assess the response to treatment.

Management overview

Anogenital warts may be difficult to treat depending on the size, location and number. There are numerous options for treatment but unlike other viruses they do not respond to anti-viral therapy.

Treatment options include:

- Topical agents: Podophyllotoxin cream 0.15%, Imiquimod cream 5%, trichloroacetic acid (TCA)

- Surgical intervention: Cryotherapy, Electrocautery, Excision

- Other options (beyond the scope of these notes): examples include 5-Fluorouracil, interferon therapy, laser or photodynamic therapy

Topical agents

Treatment may consist of topical agents that alter the immune response, induce cell death or disrupt cellular division.

Choice depends on the number, extent and size of lesions. Whether the lesions are hard and keratinised or soft and non-keratinised will also alter treatment decisions.

- Podophyllotoxin (e.g. Warticon): Good against soft lesions and can be self-applied at home. Disrupts cellular division. Clearance rate 43-70% and recurrence rate 6-55%.

- Imiquimod: Good against both hard and soft lesions. Can be self-applied at home. Stimulates a local immune response by activating macrophages. Clearance rate 35-68% and recurrence rate 6-26%.

- TCA (80-90% solution): Good against both hard and soft lesions. Applied in specialist setting. Essentially corrodes skin leading to necrosis. Clearance rate 56-81% and recurrence rate 36%.

Surgical interventions

Interventions delivered by a clinician to physically destroy the lesions using cold, heat or physical removal.

- Cryotherapy: a liquid nitrogen spray causes cytolysis of cells. Repeated treatment may be needed.

- Electrocautery: burning off the treatment site and surrounding tissue using Hyfrecation or monopolar surgery.

- Excision: lesions removed under local anaesthetic.

Vaccination

Three HPV vaccines are available within the UK, which now form part of the national vaccination programme.

The three HPV vaccines include:

- Gardasil: protective against HPV 6, 11, 16, 18

- Cervarix: protective against HPV 16 and 18

- Gardasil9: protective against five additional genotypes (31, 33, 45, 52, and 58)

In the UK, Gardasil is given to boys and girls between the ages 12-13 years old. As this vaccine covers the two most commonly implicated genotypes in anogenital warts, there is expected to be a fall in these lesions in the coming decades.

The vaccines are not licensed for patients with current HPV infections.

Complications

The most serious complication of HPV infection is development of malignancy.

HPV may lead to disfiguring lesions that are difficult to treat. The most concerning complication is development of malignancy. All women or transmen should be advised to enter the cervical screening programme.

Patients with atypical lesions or those not responding to treatment need work-up for malignancy.

Last updated: March 2021

Further reading

British Association for Sexual Health and HIV (BASHH) guidelines.

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback