Miscarriage

Notes

Introduction

A miscarriage refers to the spontaneous loss of pregnancy before 24 weeks of gestation.

Miscarriage is common, affecting up to 30% of all pregnancies. It tends to present with per vaginal (PV) bleeding that may be associated with abdominal pain/cramps. The symptoms can be dismissed as a period in early miscarriage in those who do not know they are pregnant.

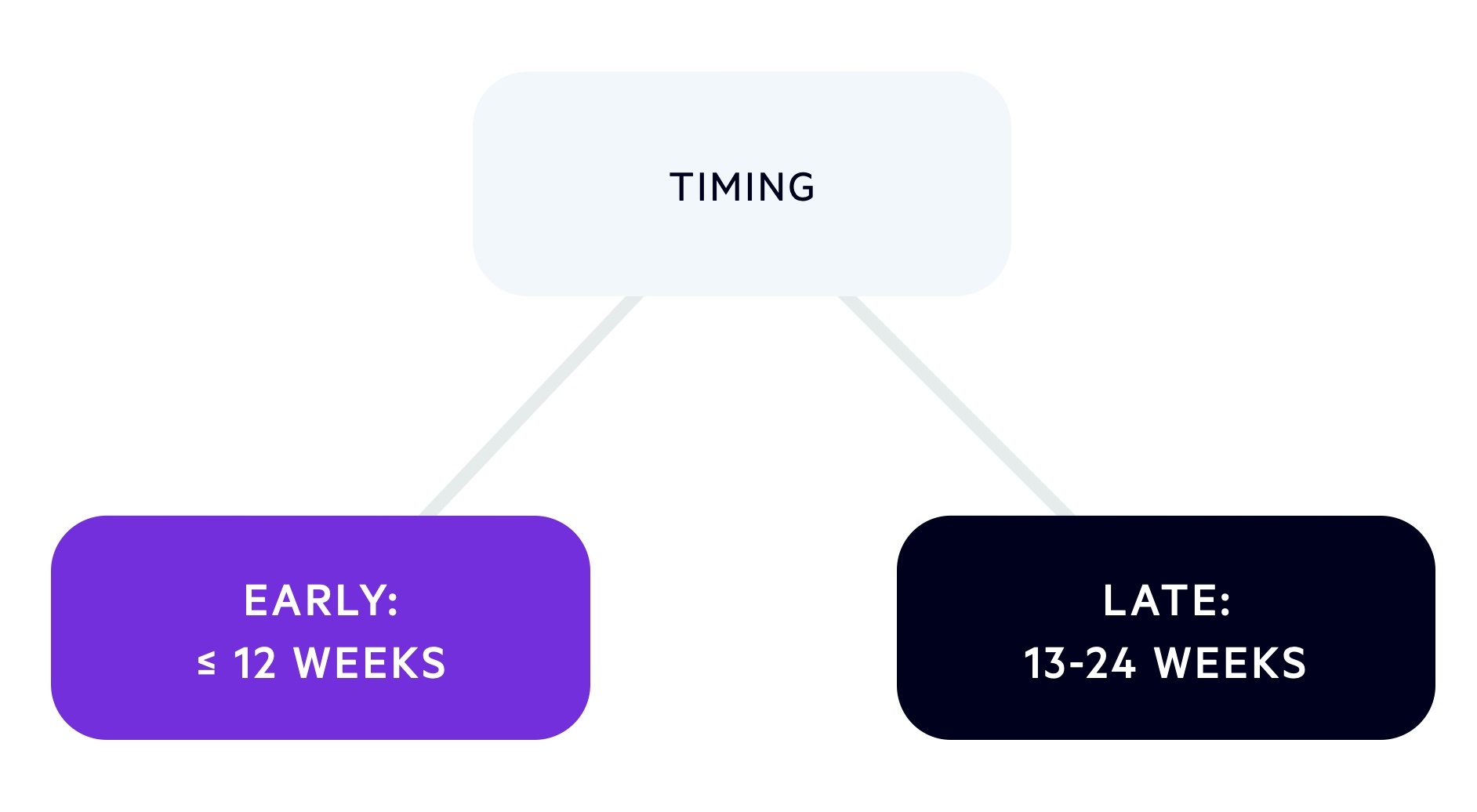

Miscarriages may be classified as early (less than 13 weeks gestation) or late (between 13 and 24 weeks gestation).

Foetal genetic/chromosomal abnormalities are the single most common cause of miscarriage though often there is no identifiable cause.

Management may be expectant, medical or surgical. Following a miscarriage, care must be given to the psychosocial wellbeing of the patient and support provided where required.

Epidemiology

Around 10-24% of clinically recognised pregnancies end in miscarriage.

Miscarriage may occur before the pregnancy is recognised, when this is taken into account up to 30% of pregnancies are estimated to end in miscarriage. Approximately 1% of women are affected by recurrent miscarriage.

Risk factors

Chromosomal abnormalities are the single most common cause of miscarriage in the first trimester.

Results from tissue specimens show an estimated 50-85% of miscarriages are associated with a chromosomal abnormality. Other genetic abnormalities can also be implicated.

Age, both maternal and paternal, is a key risk factor. Maternal age is associated with an increased incidence in miscarriage, with significant increases above the age of 35 and 40. Paternal age, particularly above the age of 40-45, increases the risk of miscarriage. Black ethnicity has also been shown to be associated with an increased risk.

Infection, particularly localised to the pelvis or systemic increases the risk of miscarriage. Appendicitis, surgical management and anaesthesia are all thought to increase the risk. Poorly controlled diabetes and thyroid disease appears to increase the risk of miscarriage as does PCOS.

The risk of miscarriage is also higher in those with a history of previous miscarriage. Other risk factors include smoking, obesity and stress. Recurrent miscarriage is discussed separately below.

Recurrent miscarriage

Recurrent miscarriage is normally defined as three or more consecutive miscarriages.

Patients with recurrent miscarriage should be referred for specialist assessment. There are a number of potential causes which should be screened for though many cases will have no identifiable cause. Some of these are discussed below:

Antiphospholipid syndrome

This is a syndrome characterised by the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies (lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin antibodies and anti-B2 glycoprotein-I antibodies) combined with vascular thrombosis and/or adverse pregnancy outcomes. It may be primary (no identifiable cause) or secondary to another condition, commonly systemic lupus erythematosus.

Antiphospholipid syndrome is a common and treatable cause of recurrent miscarriage, with the suggestive antibodies found in around 15% of women in this setting.

Genetic factors

Chromosomal abnormalities account for a large proportion of ongoing miscarriages in patients with recurrent miscarriage. The risk of chromosomal abnormalities increases with advancing maternal age.

Around 2-5% of cases of recurrent miscarriage feature one partner (maternal or paternal) with a chromosomal rearrangement, typically either a Robertsonian translocation a balanced reciprocal translocation.

Thrombophilias

Pro-thrombotic conditions increase the risk miscarriage and other complications of pregnancy. They may be inherited or acquired, two commonly implicated conditions are factor V Leiden and prothrombin mutation.

Anatomical factors

Cervical insufficiency is typically a cause of late miscarriages (and preterm labour). It is characterised by the effacement and dilatation of the cervix before normal term.

Congenital uterine malformations have also been associated with recurrent miscarriage though we are still establishing the nature and strength of this relationship.

Clinical features

A miscarriage often presents with PV bleeding and/or abdominal pain.

Miscarriage should be suspected in all women with bleeding in early pregnancy. Patients with child-bearing potential presenting to hospital should be consented for pregnancy tests where their status is unknown.

The bleeding is typically small in volume and is often associated with abdominal pain or discomfort. The key differential is an ectopic pregnancy and clinicians must be careful to exclude this.

Classification

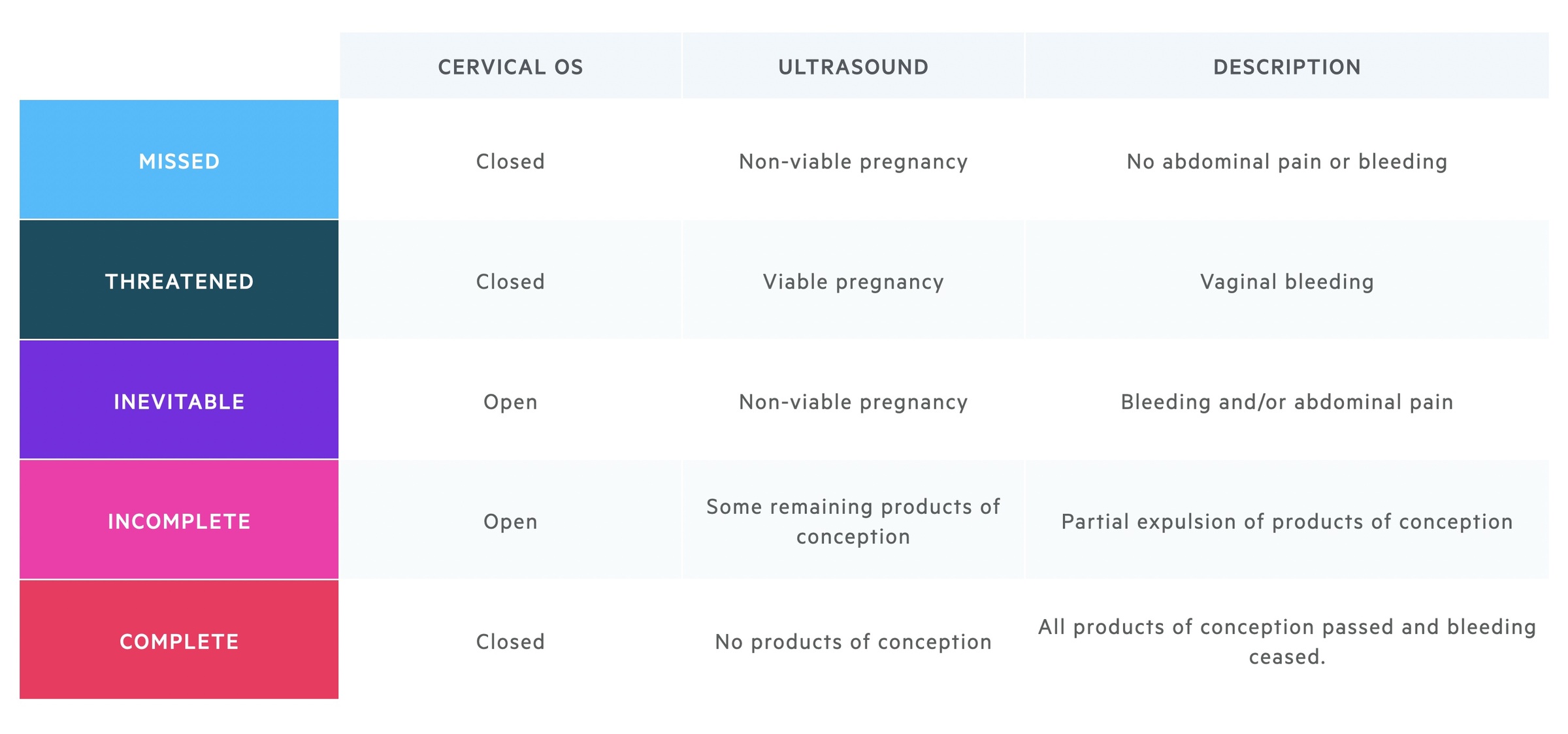

Suspected and confirmed miscarriage can be classified based upon clinical features, examination and ultrasound.

Management

The management of miscarriage may be expectant, medical or surgical.

Patients often present to their GP or A&E. Urgency of review is dependent on the clinical presentation, gestation and whether there is any concern of ectopic pregnancy. The early pregnancy assessment unit (EPAU) can provide clinical review and arrange ultrasound imaging where indicated.

More detail on the management of miscarriage can be found in NICE guideline 126 (NG 126): Ectopic pregnancy and miscarriage: diagnosis and initial management (published Apr 2019, updated Nov 2021, last accessed Nov 2021).

Initial assessment

A thorough history and examination should be completed. A transvaginal ultrasound (+/- transabdominal) should be used to confirm an intrauterine pregnancy and may establish its viability.

Where the location cannot be established patients are considered to have a pregnancy of unknown location (PUL). They require specialist follow-up with repeat USS and serial BHCG’s (and potential laparoscopy if ectopic pregnancy is suspected). The management of PUL is not covered here.

Threatened miscarriage

In the setting of a viable intrauterine pregnancy, where the patient wishes to continue with the pregnancy, the symptoms should be observed.

If stable the patient can be advised to return if symptoms worsen or do not settle after 14 days. Analgesia, written information, contact details and safety netting advice should be given.

In 2021 NICE amended guidance to add the use of vaginal micronised progesterone (400mg twice daily) for 'women with an intrauterine pregnancy confirmed by a scan, if they have vaginal bleeding and have previously had a miscarriage'. There is evidence that the progesterone may have a modest benefit in increasing the proportion of pregnancies that result in a live birth in this setting. If a foetal heartbeat is then confirmed this is continued until 16 completed weeks of pregnancy.

Expectant management

This is normally offered first-line and trialled for 7-14 days for missed or incomplete miscarriages. The majority of women will need no further medical intervention. Written information, contact details and safety netting advice should be given.

If symptoms settle after 7-14 days, women are asked to take a pregnancy test at three weeks. Should this be positive the patient should return to obstetric care.

Alternative management options should be discussed where the patient does not want expectant management, there are concerns of infection, increased risk of haemorrhage or previous adverse events in pregnancy.

Medical management

Medical management of missed or incomplete miscarriage takes the form of vaginal (preferred) or oral misoprostol. Misoprostol is a synthetic prostaglandin that stimulates uterine contractions.

Analgesia and anti-emetics should be given as is necessary. A pregnancy test is advised at three weeks, if positive specialist review is required. Written information, contact details and safety netting advice should be given.

Surgical management

Surgical management of incomplete or missed miscarriage is typically indicated where expectant or medical management fails. The two main options are:

- Manual vacuum aspiration (local anaesthetic)

- Surgical management (general anaesthetic)

Anti-D immunoglobulin should be offered to women who are rhesus negative undergoing surgical management of miscarriage.

Psychosocial wellbeing

Psychosocial wellbeing is commonly impacted following the loss of a pregnancy. Grief, mourning, depression and anxiety are common following miscarriage. Counselling and additional support should be offered where needed.

Follow up

Patients with recurrent miscarriage should be referred for specialist assessment.

General advice

As discussed above care must be taken to evaluate the wellbeing of the women and answer any questions they may have. There are numerous information leaflets and support groups that can provide additional avenues for information.

- Sex: can resume once symptoms have completely settled.

- Wish to conceive: menstruation tends to resume at 4-8 weeks, give routine pre-conception advice. Note patients may need referral to specialist services in the case of recurrent or late miscarriage.

- Do not wish to conceive: discuss and offer suitable contraceptive options.

Recurrent miscarriage

Specialist referral is made for any women with three or more miscarriages before 10 weeks gestation or one (or more) morphologically normal foetal losses after 10 weeks.

Investigations tend to include:

- Pelvic ultrasound

- Antiphospholipid antibodies

- Thrombophilia screen

- Maternal and paternal karyotype

- Foetal genetic analysis

As discussed above antiphospholipid syndrome is a common and treatable cause of recurrent miscarriage. Management depends on the individual, co-morbidities, blood results (in particular their platelet count!) and their history of either thrombosis or adverse events in pregnancy. In women whose only clinical manifestation is recurrent pregnancy loss, management is typically with aspirin and low molecular weight heparin during the pregnancy with additional close monitoring.

When a genetic abnormality is found during the parental screen a referral is made to a clinical geneticist to allow them to further explain the findings and its potential implications.

Last updated: July 2021

Further reading

RCOG: Green-top Guideline No. 17 - Recurrent Miscarriage, Investigation and Treatment of Couples (2017 update)

NICE NG 126: Ectopic pregnancy and miscarriage: diagnosis and initial management (2019)

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback