HIV

Notes

Introduction

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a retrovirus that, when untreated, causes progressive immunodeficiency with resulting susceptibility to opportunistic infections and malignancies.

HIV was first identified in 1983, two years after the first description of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). AIDs refers to a state of immunodeficiency that results from infection with HIV, typically taking several years (median 8-10) following exposure to develop. In the UK there has been a move away from the term AIDs, which is still bound by significant stigma, to late-stage HIV. It is characterised by a CD4 count < 200 and/or AIDs defining illnesses. Prior to effective treatment people with HIV/AIDs were susceptible to opportunistic infections, the development of malignancies and eventually death.

Over the decades that followed its discovery, our understanding of the virus grew and increasingly effective therapies were developed. In the late 1990’s the development of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) marked a significant step forward in the medical management of the condition.

Today, modern therapies mean that once diagnosed, the majority of individuals can live relatively or entirely normal lives. Early diagnosis and initiation of antiretroviral therapy are key to reducing morbidity and mortality. When caught and treated early the majority of patients will never develop late-stage HIV and can often expect a life expectancy similar to the general population.

As important as treating HIV is reducing late diagnosis and new acquisition. Effective treatment, public health efforts, educational campaigns, reducing stigma and novel therapies like pre-exposure prophylaxis (PREP) are helping to reduce transmission.

Epidemiology

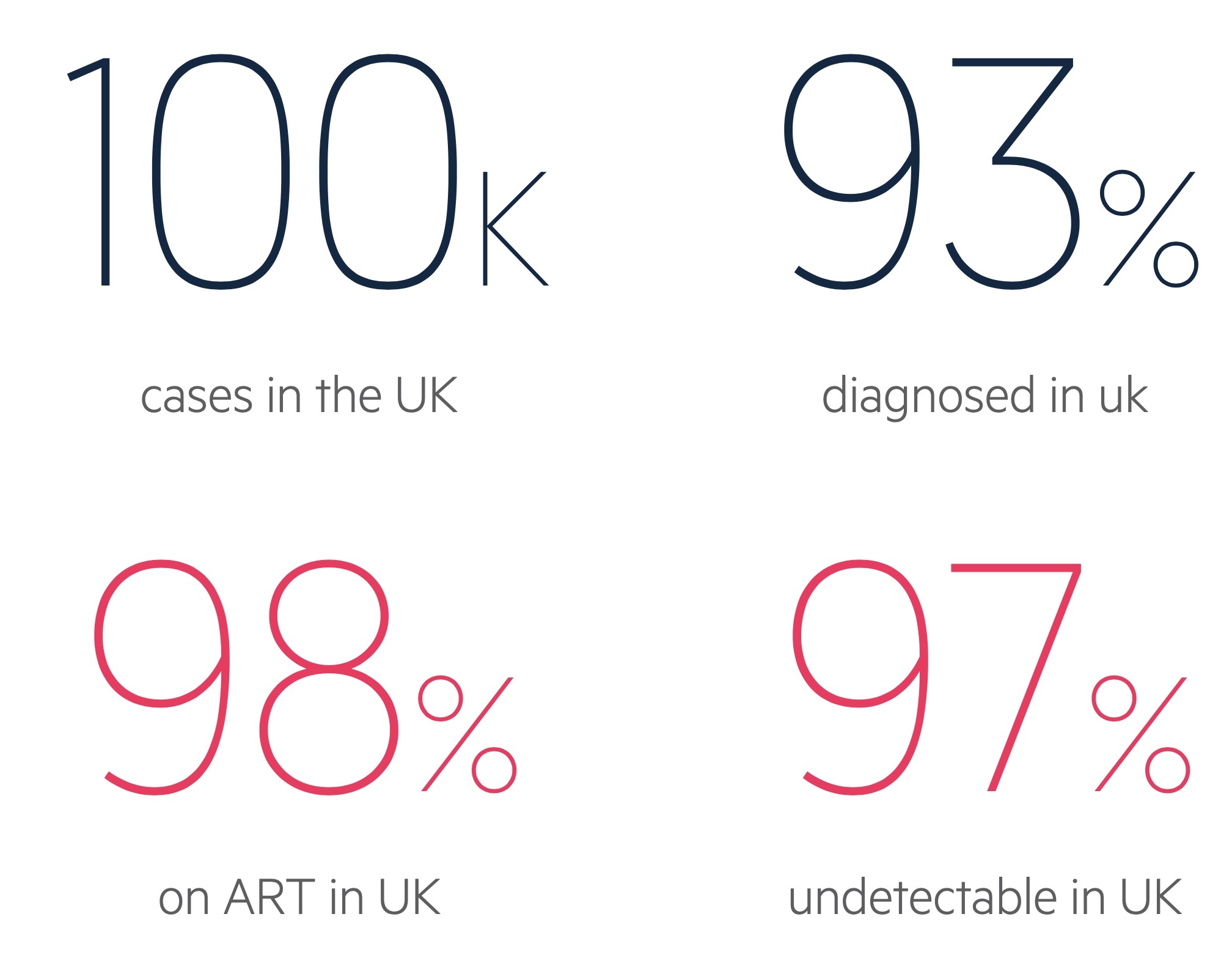

In the UK there were an estimated 103,800 people with HIV in 2018.

Of these people, approximately 93% were diagnosed leaving an estimated 7% undiagnosed. Of those diagnosed, 98% were on antiretroviral therapy. Of patients engaged with services with a recorded viral load in 2017, 97% had an undetectable viral load. Figures from BHIVA testing guidelines.

The efforts of public health bodies, HIV/GUM and public engagement have led to a continued reduction in community transmission. Rates of transmission fell by 10% between 2018 and 2019. The aim is to entirely eliminate HIV transmission in the UK.

Worldwide HIV is estimated to affect 38 million people. Of these, approximately 68% of adults and 53% of children were on life-long antiretroviral therapy. There were 690,000 HIV-related deaths and 1.7 million new infections in 2019. Figures from WHO.

The UN AIDs programme had set the goal of reaching ’90-90-90’ by 2020. The aim was for countries to diagnose 90% of cases, with 90% on treatment and 90% achieving viral suppression. Though many countries were unable to achieve this, the goal for 2030 is 95-95-95.

Pathogenesis

HIV is a lentivirus, a genus within the family of retroviruses.

There are two forms of HIV virus:

- HIV-1: most common strain, found worldwide. The focus of this note will be HIV-1.

- HIV-2: less common, it was first identified in 1986 in West Africa where it remains largely restricted (cases are rising in other locations). Co-infection may occur. HIV-2 appears to be less pathogenic, with a slower course and lower mortality.

HIV type 1 has glycoprotein-120 (GP-120), a viral envelope protein, which attaches to cluster of differentiation 4 (CD4) found on a number of immune cells. This process is assisted by binding of a co-receptor on the host cell. There are two major types of virus based on the co-receptor:

- R5: Macrophage trophic R5 viruses with the CCR5 co-receptor

- X4: T-cell trophic X4 viruses that utilise CXCR4.

Both strains are transmitted but in the early stage of disease, the R5 predominates. Interestingly, in the relatively rare occurrence of homozygous deletion of CCR5, patients have a resistance to infection. There is also a dualtrophic strain though we don't discuss that further here.

HIV produces three key enzymes, reverse transcriptase, protease, and integrase. Reverse transcriptase facilitates the transcription of viral RNA to DNA which is incorporated into the host cells own genome catalysed by integrase. HIV-1 protease is important in protein processing. This leads to the production of more viruses, driven by the host's own cells.

Transmission

The spread of HIV is most commonly via sexual transmission, there were 1.7 million new infections worldwide in 2017.

Routes

HIV is found in many body fluids but transmission normally occurs via semen, cervical secretions and blood. The viral load, highest during an acute infection, is a marker for the risk of transmission.

- Sexual transmission: worldwide heterosexual sex is responsible for the majority of infections. As a general rule transmission is more likely with anal intercourse compared to vaginal, and more likely for the one receiving than the one inserting. Female to male transmission is less efficient and transmission is less common with oral sex. Concomitant STI's appear to increase the risk of tranmission. Patient successfully maintained on treatment with an undetectable viral load have been shown to have effectively zero risk of sexual transmission.

- Vertical transmission: this refers to mother to baby transmission. Without treatment this can be as high as 15-40%. Transmission may occur in utero, though more commonly occurs in the peri-natal period. Breast feeding also increases the risk of transmission. Screening, anti-retroviral therapy and when possible avoidance of breast feeding significantly reduces the risk of transmission.

- Contaminated needles: shared and re-used needles are a significant risk factor for blood borne viruses. Education and needle exchanges can help to reduce this mode of transmission.

- Contaminated blood products and organs: modern screening techniques (in countries where this is available) has dramatically reduced the risk of this transmission route. However there are many patients affected from historical practice prior to effective screening.

At-risk groups

Though everyone is at risk of exposure to HIV, there are a number of groups that are at increased risk:

- Men who have sex with men (MSM)

- Female sexual contacts of MSM

- Trans women

- Black Africans

- Those from a country with high diagnosed seroprevalence

- Those with sexual contact with anyone from a country with high seroprevalence

- Those with a mother with HIV who have not themselves been tested

- Those who use injectable drugs

- Sex workers

- Prisoners

Natural history

In the absence of treatment, HIV tends to follow a three-stage course; acute infection, chronic infection and late stage HIV / AIDs.

Acute infection

The initial infection often presents with a flu or mononucleosis type infection. Symptoms are non-specific and can be relatively mild and as such may be dismissed by both patients and clinicians alike. This acute illness occurs 1-6 weeks after infection and results from seroconversion - which refers to the development of antibodies to HIV.

A significant proportion (estimated at 10-60%) are entirely asymptomatic during the early phases of the illness.

In those who are symptomatic features include:

- Fever

- Lymphadenopathy

- Sore throat

- Oral ulcers

- Myalgia

- Malaise

- Diarrhoea

- Rash

- Headache

Chronic infection

After around six months the viraemia reaches a relative steady state. There is a period of stability in terms of the viral load, with a gradual fall in the CD4 lymphocyte count. During this latent phase of the disease patients tend to be asymptomatic. In the absence of treatment the length of this phase varies significantly, but on average is 8-10 years.

AIDs/late-stage HIV

After a patient's CD4 count falls below 200 cells/mm3 the patient is said to have late-stage HIV. There is a significant increase in the risk of developing AIDs defining illnesses and patients can present with fatigue, malaise, weight loss, opportunistic infections and malignancies.

There are a huge number of AIDs defining illnesses. These are conditions typically seen in patients with late-stage HIV (though they can be seen in other settings). They can globally be divided into opportunistic infections (OI’s) and malignancies. We present a selection (not exhaustive) of these below:

- Neoplasms:

- Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

- Kaposi’s sarcoma

- Cervical cancer

- Bacterial infection:

- Mycobacterium tuberculosis

- Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC)

- Recurrent pneumonia

- Viral infection:

- Cytomegalovirus

- Herpes simplex

- Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy

- Fungal infection:

- Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP)

- Candidiasis

- Cryptococcosis

- Histoplasmosis

- Parasitic infection:

- Cerebral toxoplasmosis

- Cryptosporidiosis

- Atypical disseminated leishmaniasis

Untreated patients with late-stage HIV have a median survival of 12-20 months. If diagnosed at this stage patients require careful and detailed examination and investigation. After the initiation of treatment, they are at risk of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS). IRIS describes an elevated inflammatory response, as the immune system recovers, against pre-existing opportunistic infections.

Testing

Early detection reduces delay to diagnosis, complications and ongoing transmission of HIV.

Who to test?

There has been a move to increase testing for HIV in the UK. The aim is to continue to reduce the proportion of patients (currently around 7%) with undiagnosed infection. This is key to both improve the outcomes for individual patients as well as reduce ongoing transmission.

Universal screening is not supported in the UK where the undiagnosed prevalence was estimated to be 0.016% in 2018 for those aged 15-74. However wherever the prevalence is estimated to be 0.1% it is considered cost effective (a lower threshold is used in the antenatal setting).

Patients should be informed of the reason and implications of testing (with all questions answered), but a ‘lengthy pre-test discussion is not required’.

As such the 2020 BHIVA guidelines recommend testing:

- People belonging to groups at increased risk of exposure to HIV, including men who have sex with men (MSM) and their female sexual partners, black Africans, people who inject drugs (PWID), sex workers, prisoners, transwomen and people from countries with high HIV seroprevalence and their sexual partners.

- People attending health services whose users have an associated risk of HIV, including sexual health services, tuberculosis (TB), hepatitis and lymphoma clinics, antenatal clinics, termination of pregnancy services and addiction and substance misuse services.

- All people presenting with symptoms and/or signs consistent with an HIV indicator condition.

- People accessing healthcare in areas with high (>2/1000; if undergoing venepuncture) and extremely high (>5/1000; all attendees) HIV seroprevalence.

- In those requiring repeated testing, frequency is dictated by the individuals ongoing risk factors.

Testing technology

There are two main methods for the testing of HIV:

- Laboratory testing (sample taken via venepuncture)

- Self-sampling, self-testing and rapid point of care tests (POCTs)

There is a window between when exposure to HIV occurs and when a test returns a consistent and accurate result. This is typically between 45 and 90 days for most standard tests - as such caution, counselling (i.e. the risk of a false negative) and potential repeat testing should be considered in those presenting early.

The latest fourth-generation laboratory tests are based on HIV antibody detection and HIV p24 antigen detection. They have a window of 45 days (99% of infections detected after 45 days). A positive result is confirmed with a HIV-1/HIV-2 differentiation immunoassay.

Investigations

Baseline investigations help to guide management and further tests in patients with a new diagnosis of HIV.

Baseline investigations aim to confirm the diagnosis, assess the degree of immunosuppression, identify co-existing conditions and any drug resistance. This is a summary of key investigations, the truth is far more complex, particularly in those presenting with late-stage HIV. Routine tests include:

- HIV-1/HIV-2 differentiation immunoassay

- HIV-1 viral load

- Genotypic resistance

- CD4+ T cell count

- Viral hepatitis serology

- Full STI screen (including syphilis serology)

General biochemistry tests ordered for all patients include FBC, renal function, LFT and a bone profile. A urine dipstick should be completed, if proteinuria is found a protein/creatinine ratio should be sent.

All patients should have their height, weight, BMI, waist circumference and blood pressure recorded. If relevant, cardiovascular risk factors and bone mineral density should be reviewed.

Women should be offered cervical cytology if aged between 25-64 without one in the past year or if they have never had it.

There are many more tests that may be organised based on the presentation, examination findings, results of investigations and proposed treatments.

Management

Anti-retroviral therapy forms the mainstay of management for patients with HIV.

Overview

The management of HIV is enormously complex. It is tailored to the individual and their wishes, co-morbidities, CD4 and viral load at presentation and the presence of any complication or co-infection. As such the below text represents a significant simplification of the process. For those interested in more detail check out the BHIVA and European Aids Clinical Society guidance.

The diagnosis of HIV can be an enormously challenging time in someones life. Psychological support and counselling should be offered to all patients. The diagnosis, treatment options and future implications should be discussed.

Anti-retroviral therapy (ART) has transformed the management of HIV. Regimens aim to reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with HIV whilst minimising any treatment-related side-effects. Fortunately, with time the number of pills and severity of side effects have been reduced. The vast majority of patients can expect to be commenced on an ART that is tolerable and enables them to live an otherwise normal life.

As important as treating an individual's condition is reducing the onward spread of the disease. This is of particular relevance to women planning to have children and serodifferent couples (couples where one partner is positive and one is negative). Importantly, the PARTNER study has indicated that those effectively established on treatment with an undetectable viral load have effectively no risk of onward sexual transmission.

ART

A typical regimen will consist of:

- Two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs)

- A third agent, typically one of:

- Ritonavir-boosted protease inhibitor (PI/r)

- Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI)

- Integrase inhibitor (INI)

An example regime would be tenofovir-DF and emtricitabine (the NRTI backbone) and atazanavir (protease inhibitor) boosted with ritonavir. Excellent adherence is required to both adequately suppress the virus and to prevent the development of resistant strains.

Initiating treatment is more complex in those presenting with AIDs/late-stage HIV, particularly if there is a concomitant significant infection, hepatitis or malignancy. The details of this are beyond the scope of this note.

Patients and clinicians must be aware there are complex interactions between ARTs and many other medications. The Liverpool Drug Interaction Checker is a great tool to evaluate for possible interactions.

Click here for our ART notes.

Monitoring

Monitoring must be guided by the patient, their presentation and any existing complications. Each review is an opportunity to discuss how they are coping, if there are any issues they would like to discuss or questions to have answered. Low mood should be screened for as should chronic conditions like diabetes, cardiovascular disease, renal disease and osteoporosis.

Two key tests in the monitoring of HIV are:

- Viral load: the aim of treatment is to achieve an undetectable viral load (< 20 or < 50 copies of viral genome/mL blood depending on the test). After treatment is established and suppression is achieved (a period in which testing is more frequent), testing tends to be repeated every 6-12 months.

- CD4 count: measured more frequently after a new diagnosis and in those with low CD4 counts. Once established on treatment with a suppressed viral load and two readings > 350 a year apart routine testing is not necessarily needed.

Prognosis

Patients who are diagnosed early and initiated on effective ART with suppression of viral load can expect life-expectancy equivalent to the general population.

Early diagnosis, initiation of ART and suppression of viral load are key to obtaining good outcomes. Though the figures can be hard to interpret it appears those diagnosed early and managed well on ART with an undetectable viral load and CD4 > 350 have a normal (or perhaps slightly improved) life expectancy.

The longer patients go undiagnosed, particularly if they develop a suppressed CD4 count, the poorer outcomes become and the higher the risk of developing opportunistic infections and malignancies. Without treatment, patients with AIDs tend to have an average survival of 12-20 months.

Last updated: July 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback