Acute mesenteric ischaemia

Notes

Introduction

Mesenteric ischaemia refers to insufficient blood supply to the small intestines leading to ischaemic and inflammatory changes.

The terminology surrounding intestinal ischaemia can be confusing at times with certain terms used interchangeably. For the purposes of this note we define the following terminology (in line with the general consensus):

- Colonic ischaemia: refers to ischaemia affecting the colon.

- Mesenteric ischaemia: this term tends to be reserved to describe ischaemia affecting the small intestines.

Mesenteric ischaemia can be divided into two major categories: acute and chronic. Acute mesenteric ischaemia (AMI) results from the acute insufficiency of blood supply to the small intestines. It is relatively uncommon but carries significant morbidity and mortality when it occurs. As such, prompt recognition and management are essential for good outcomes.

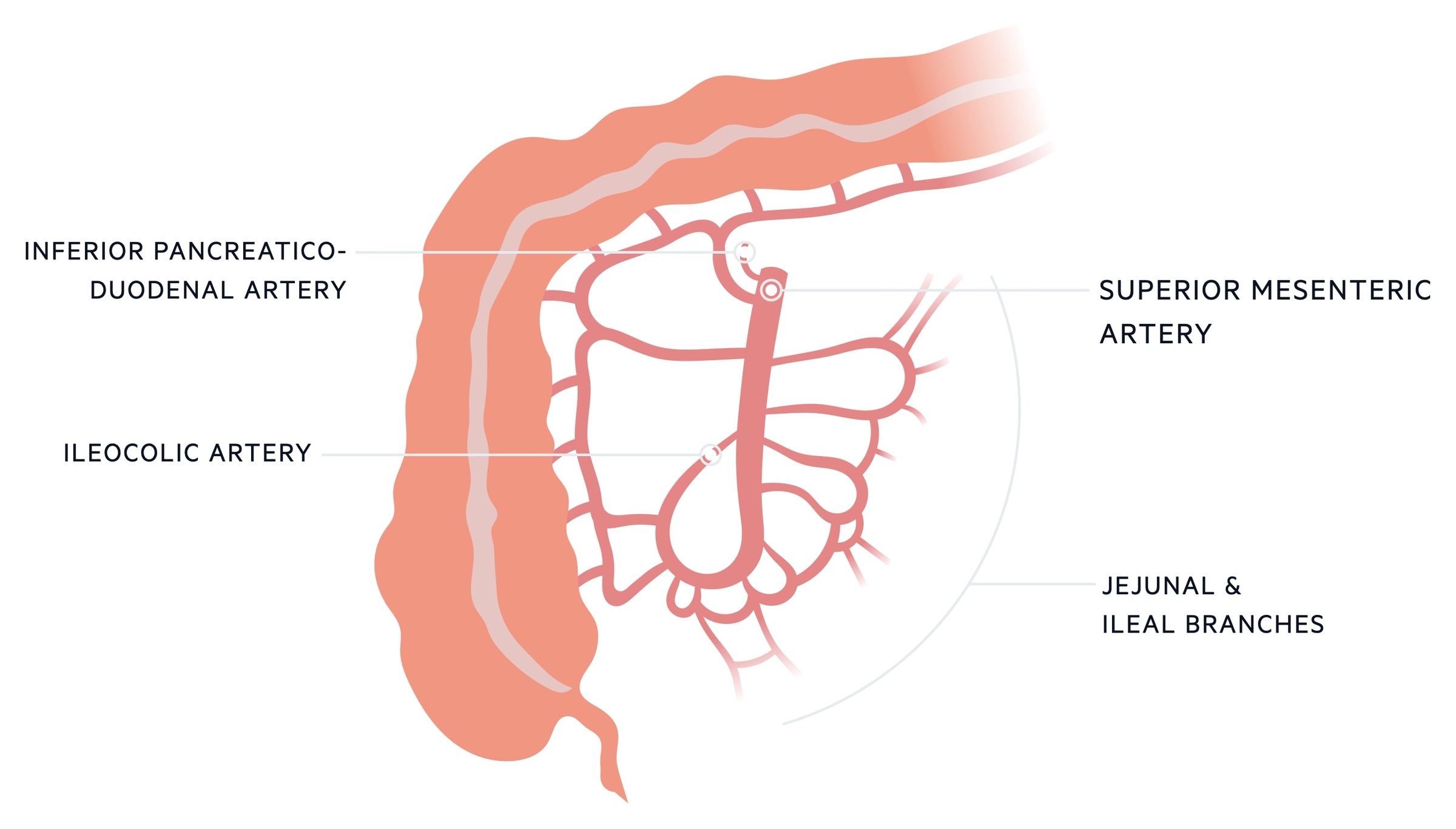

Blood supply

The blood supply to the small intestines is primarily from the superior mesenteric artery with additional contribution from the coeliac axis.

Foregut (duodenal component)

The foregut extends from the mouth through to the second part of the duodenum (until the ampulla of Vater). As such only a short segment of the small intestines is part of the foregut. The gastroduodenal artery supplies blood to the stomach, duodenum and pancreas. It is a branch of the common hepatic artery, itself a branch of the coeliac axis.

The anatomy of the gastroduodenal artery (its origin and branching) is highly variable. However, the duodenum typically receives blood supply from the anterior and posterior superior pancreaticoduodenal artery.

The anastomosis of the superior pancreaticoduodenal artery and inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery (from the superior mesenteric artery) means the duodenum has a rich, well-collateralised dual blood supply. It is therefore relatively rare to suffer from duodenal ischaemia.

Midgut (small intestinal component)

The midgut extends from the second part of the duodenum to approximately two-thirds along the way of the transverse colon. The superior mesenteric artery (SMA), the major artery of the midgut, arises from the abdominal aorta at the L1 vertebral level. It supplies the small intestines, ascending and transverse colon (see our notes on Colonic ischaemia for more on the SMA’s supply to the colon).

It provides a number of branches that supply the small intestines:

- Inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery: comes off the right side of the SMA supplying both the pancreas and duodenum. It anastomoses with the superior pancreaticoduodenal artery.

- Jejunal branches: these come off the left side of the SMA. There are typically 4-6 branches supplying the jejunum.

- Ileal branches: these come off the left side of the SMA distal to the jejunal branches. There tend to be more, typically 8-12 branches.

The superior mesenteric vein (SMV) drains the distribution of the SMA. It joins the splenic vein to form the portal vein which travels to the liver.

Subtypes

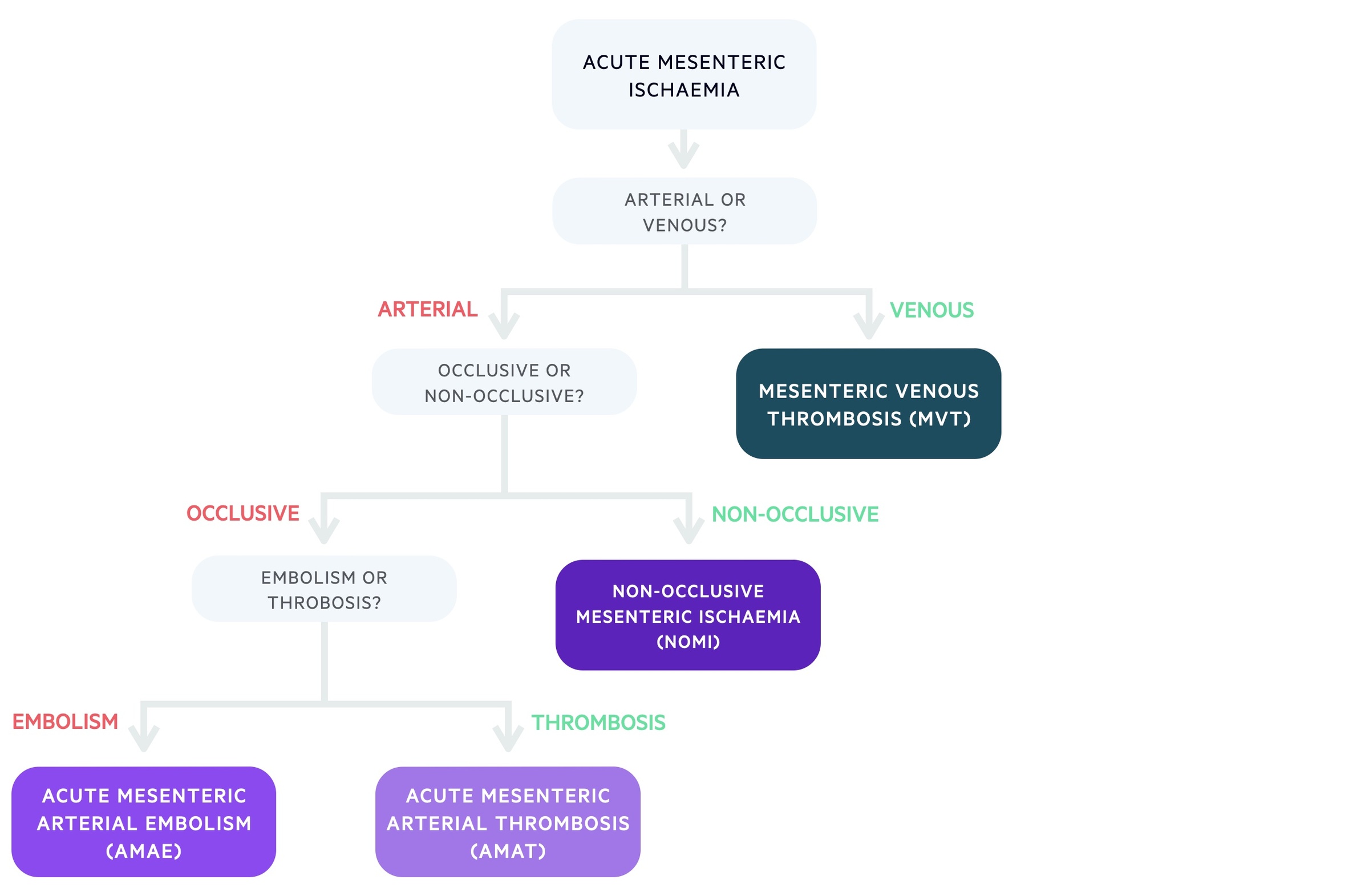

AMI refers to a collection of conditions causing acute intestinal hypoperfusion.

The causes of AMI can be categorised based on whether they are caused by arterial or venous disease. Mesenteric venous thrombosis (MVT) is the venous cause of AMI, where blockage of venous drainage leads to impaired blood supply to the intestines.

Arterial causes of AMI may be occlusive or non-occlusive. Occlusive arterial AMI can be related to either embolic disease (acute mesenteric arterial embolism, AMAE) or thrombotic disease (acute mesenteric arterial thrombosis, AMAT). Non-occlusive mesenteric ischaemia (NOMI) is caused by arterial spasm/vasoconstriction.

AMAE

Acute mesenteric arterial embolism (AMAE) is caused by emboli blocking the SMA. An embolus is a mass that passes through blood vessels eventually blocking it if the calibre narrows sufficiently given the size of the embolus. An embolus can be theoretically anything from air to fat. In the case of AMAE, it is normally a blood clot that becomes detached from the heart or vessel wall and floats through the blood before becoming stuck.

It is estimated that around 50% of cases of AMI are due to AMAE. Any condition that causes proximal thrombus formation can predispose patients to AMAE:

- AF (thrombus formation in the left atrium due to turbulent blood flow)

- Infective endocarditis (septic emboli)

- Myocardial infarction (with mural thrombus secondary to impaired muscle function)

- Aortic thrombus (often seen in aortic aneurysms)

Parts of thrombus (or infective masses) can break off and enter the systemic circulation as emboli. The SMA’s low angle of take-off from the aorta and large opening puts it at particular risk for embolisation. Pre-existing atherosclerosis, narrowing the vessel, increases the risk of an embolus lodging in the vessel. The embolus typically blocks the artery 3-10cm from its origin, often sparing the middle colic and jejunal branches from involvement (as these branch off more proximally).

AMAT

Acute mesenteric arterial thrombosis (AMAT) is caused by thrombosis, normally on the background of pre-existing atherosclerosis. It is thought to account for around 20-25% of cases of AMI. There is often a history consistent with chronic mesenteric ischaemia (e.g. abdominal pain, weight loss). Though atherosclerosis is the most commonly implicated, other causes of arterial thrombus include:

- Vasculitis

- Traumatic injury

- Infection

- Mesenteric aneurysm/dissection

NOMI

Non-occlusive mesenteric ischaemia (NOMI) is caused by arterial spasm or vascoconstriction as opposed to occlusive disease. It is thought to be the cause of around 20% of cases of AMI and may involve the proximal colon.

The condition is most commonly seen in patients on ITU who are severely unwell, typically with impaired cardiac function and/or vasopressor use.

MVT

Mesenteric venous thrombosis (MVT) is caused by thrombosis of the venous drainage of the small intestines. It is thought to account for around 10% of cases of AMI.

Blockage of the venous drainage results in increasing back pressure building up in the venous beds. As the pressure rises, fluid is forced out causing bowel wall oedema. These processes impair the blood supply to the intestines and may also result in secondary arterial vasospasm further worsening the condition.

It tends to occur in patients with risk factors for hypercoagulability, these include:

- Systemic factors:

- Inherited thrombophilia (e.g. factor V Leiden, protein C and S deficiency)

- Malignancy

- Medications (e.g. oral contraceptive)

- Local factors:

- Venous compression (secondary to tumours)

- Inflammatory conditions (e.g. pancreatitis, IBD)

- Surgical trauma

Clinical features

Severe abdominal pain is characteristic of AMI.

AMI most commonly presents with abdominal pain that is often poorly localised. The pain can be severe and may be out of keeping with what is expected based on the examination. Clinical examination reveals tenderness, the development of peritonism is indicative of advanced ischaemia and necrosis. As the condition worsens fever becomes common and haemodynamic instability can occur.

Clinical features may also reflect the underlying aetiology. For example, patients with AMAE may be in AF (irregularly irregular pulse). Patients with NOMI will typically have an underlying illness and be severely unwell. It is often seen in the ITU setting in patients with impairment of normal cardiac function on vasopressor support.

Symptoms

- Abdominal pain

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Diarrhoea

- Blood in stools

Signs

- Abdominal tenderness

- Guarding/peritonism

- Tachycardia

- Pyrexia

- Hypotension

Investigations

CT abdomen and pelvis with contrast is the diagnostic modality of choice for AMI.

Observations should be recorded and blood sugar routinely measured. Blood tests may show a non-specific rise in the inflammatory markers (WCC and CRP), a raised lactate and metabolic acidosis. Other non-specific signs on blood tests include a raised D-DIMER and mild elevation of amylase.

Investigations may also be guided by the suspected underlying cause. For example, a thrombophilia screen may be sent in a patient with MVT.

Bedside

- Observations

- Blood sugar

- ECG (check for arrhythmias, particularly AF)

- Pregnancy test (if appropriate)

Bloods

- FBC

- Renal function

- CRP

- LFT

- Amylase

- Clotting screen

- Group and screen

- VBG/ABG (lactate, pH balance)

Imaging

Erect CXR: may reveal pneumoperitoneum if necrosis and perforation have occurred.

CT abdominal/pelvis: this is generally the diagnostic modality of choice. It offers good sensitivity and also allows alternative causes of abdominal pain to be excluded.

Echocardiogram: may be ordered if a central source of embolus is suspected (e.g. valvular endocarditis, ventricular thrombus).

Management

The management of AMI is complex but involves optimal supportive care and often surgical intervention.

Medical management

IV access with wide-bore cannula should be gained. Appropriate fluid resuscitation should be commenced with close monitoring of haemodynamic stability. A nasogastric tube should be placed.

Broad-spectrum antibiotics should be started due to the risk of bacterial translocation across the gut wall and the risk of perforation. Anticoagulation with unfractionated heparin (UFH) is typically started unless there is a contra-indication.

MVT

In patients with MVT without signs of peritonitis or perforation, anticoagulation (with UFH) can be used as the definitive management. Close monitoring is required and surgical intervention must be considered if the clinical situation deteriorates.

NOMI

In patients with non-occlusive disease treatment of the underlying cause is of the utmost importance. This may involve optimisation of cardiac output and altering or reducing the vasopressors used.

Vasodilators like papaverine may be used to improve blood flow to the intestines. Again surgical management can be required if there are signs of peritonitis, perforation or clinical deterioration. This is not a decision taken lightly as given the often poor pre-morbid state the mortality of any surgery is very high.

Surgical management

The decision to operate depends on the underlying aetiology, patient factors and patient wishes. It should be made by a senior surgical decision-maker. Prompt laparotomy is typically required in patients with peritonitis or radiological evidence of advanced ischaemia.

The National Emergency Laparotomy Audit (NELA) records and reviews emergency laparotomies and identifies ways in which practice can improve. They have outlined a number of standards, for those that are interested more information can be found here.

All emergency laparotomies should be recorded with data submitted to NELA. The NELA risk calculator can be used to give an estimate of a patient's 30-day mortality.

Laparotomy allows for direct assessment of the intestines. Non-viable sections of bowel will require resection, decisions regarding stoma formation or primary anastomosis should be made at a consultant level. In occlusive disease (AMAT, AMAE), laparotomy can also be used to attempt revascularisation:

- AMAE: SMA emboli can be treated with embolectomy.

- AMAT: Diffuse thrombosis may be treated with a bypass graft.

It may not be possible to conclusively assess and treat AMI during a single operation. A re-look laparotomy is often required to check the viability of intestines and to make final decisions regarding resection, creating an anastomosis or forming a stoma.

Endovascular management

Endovascular techniques may be used in appropriately selected patients where local expertise allows. It can only be used in stable patients without any clinical or radiological evidence of advanced ischaemia and necrosis. Research is ongoing to define the patient population in whom endovascular intervention should be used, and the relative risks and benefits.

In patients with AMAE/AMAT, endovascular interventions involve obtaining vascular access (typically via the femoral or brachial artery) and identifying the arterial occlusion. The blockages may be resolved through a variety of techniques including mechanical aspiration, localised thrombolysis and/or angioplasty +/- stenting.

Some studies have looked at localised thrombolysis/thrombectomy for patients with MVT. This therapy is in the early stages of development and is typically only performed at specialist centres as part of research.

Last updated: April 2022

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback