Melanoma

Notes

Summary

Melanoma is a cancerous growth of melanocytes.

NB - This article is in reference to cutaneous melanoma only.

Melanoma is common. In the UK, it accounts for approximately 4% of all new cancers. It results from a combination of environmental and genetic factors.

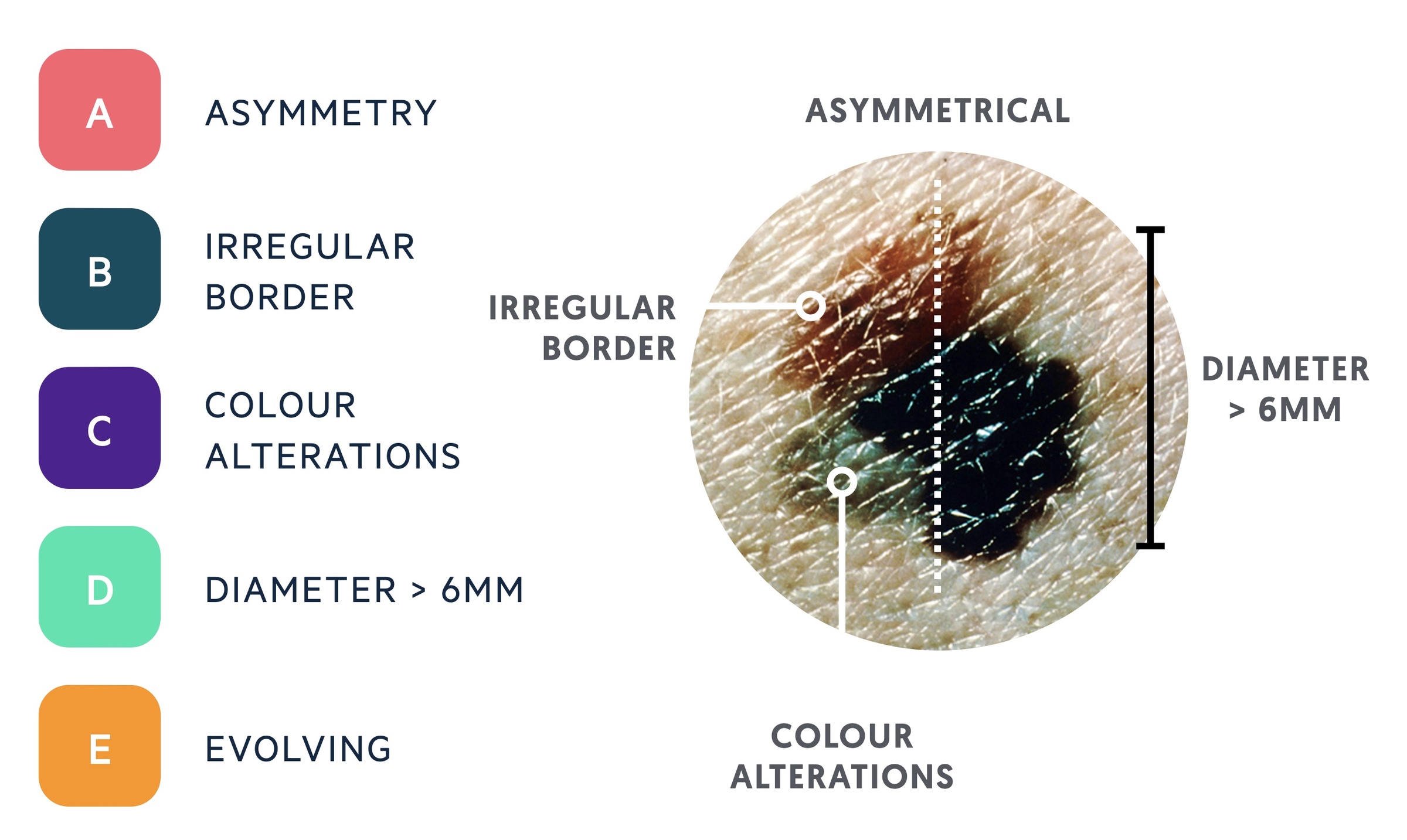

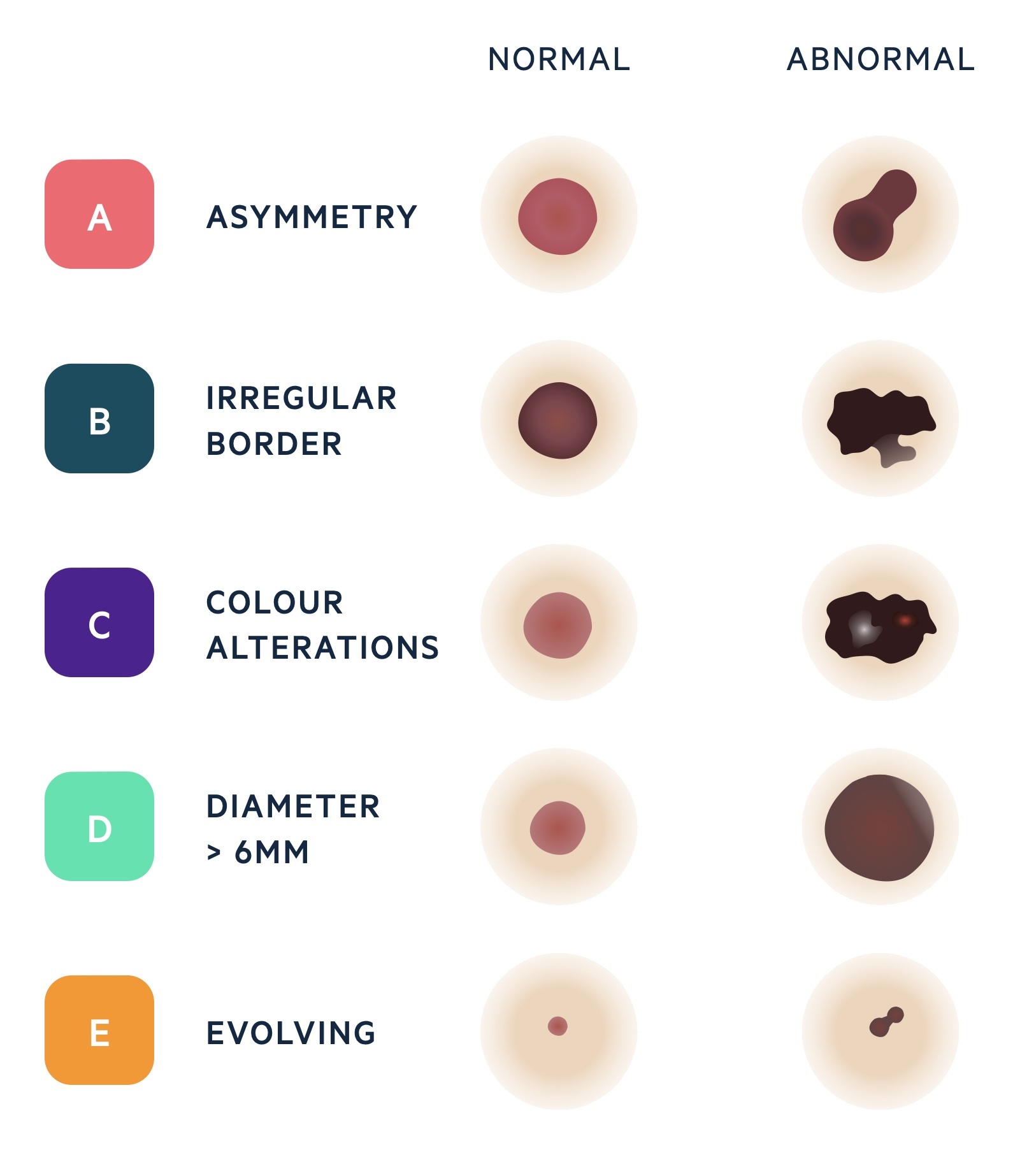

Features suspicious of melanoma can be remembered using the mnemonic 'ABCDE':

- Asymmetry

- Border (irregular)

- Colour alterations

- Diameter > 6mm

- Evolving lesion

Patients with a suspicious lesion are referred for a tissue biopsy. In most instances, this constitutes an excisional biopsy with a 2 mm margin.

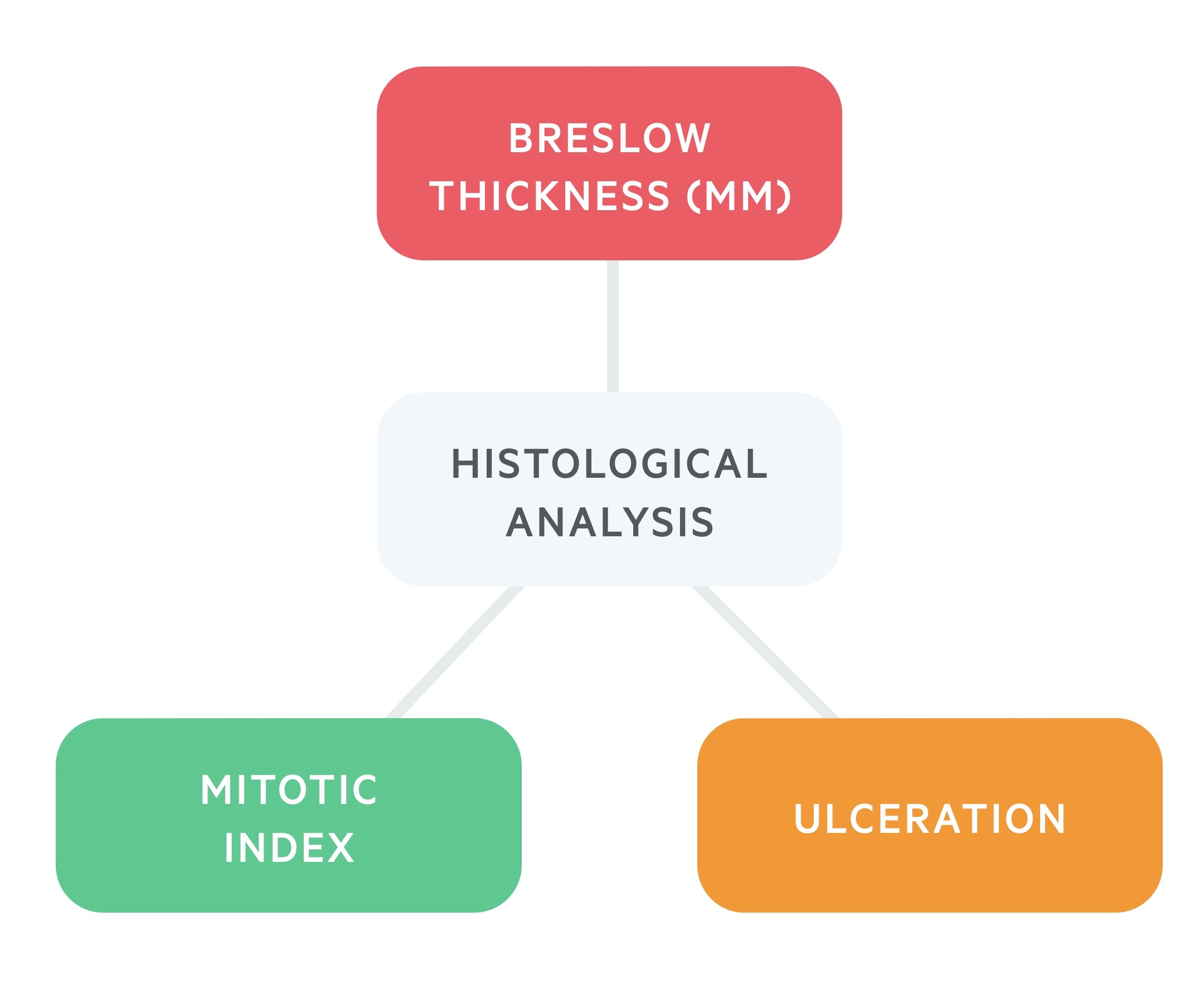

If diagnostic of melanoma, the Breslow thickness, presence of ulceration and the mitotic index are used to histologically stratify the disease. Staging of melanoma is based on the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) system.

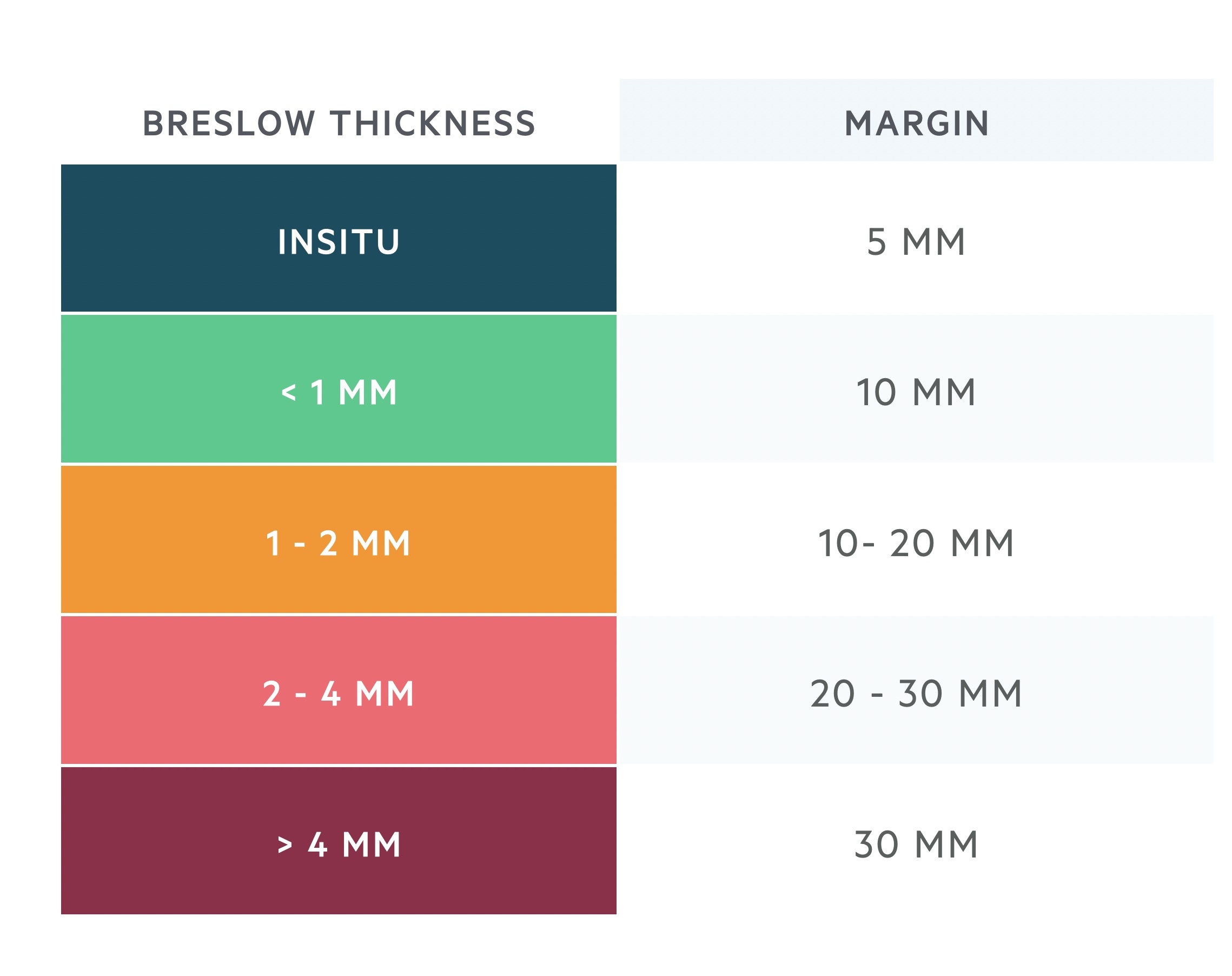

Management is complex. Wide local excision (WLE) is the standard treatment for local disease, with the size of the excision margin guided by the Breslow thickness (e.g. <1mm = 1 cm).

NB - Where possible we have included images of melanoma in dark-skinned people or where these could not be obtained, detailed descriptions.

Aetiology

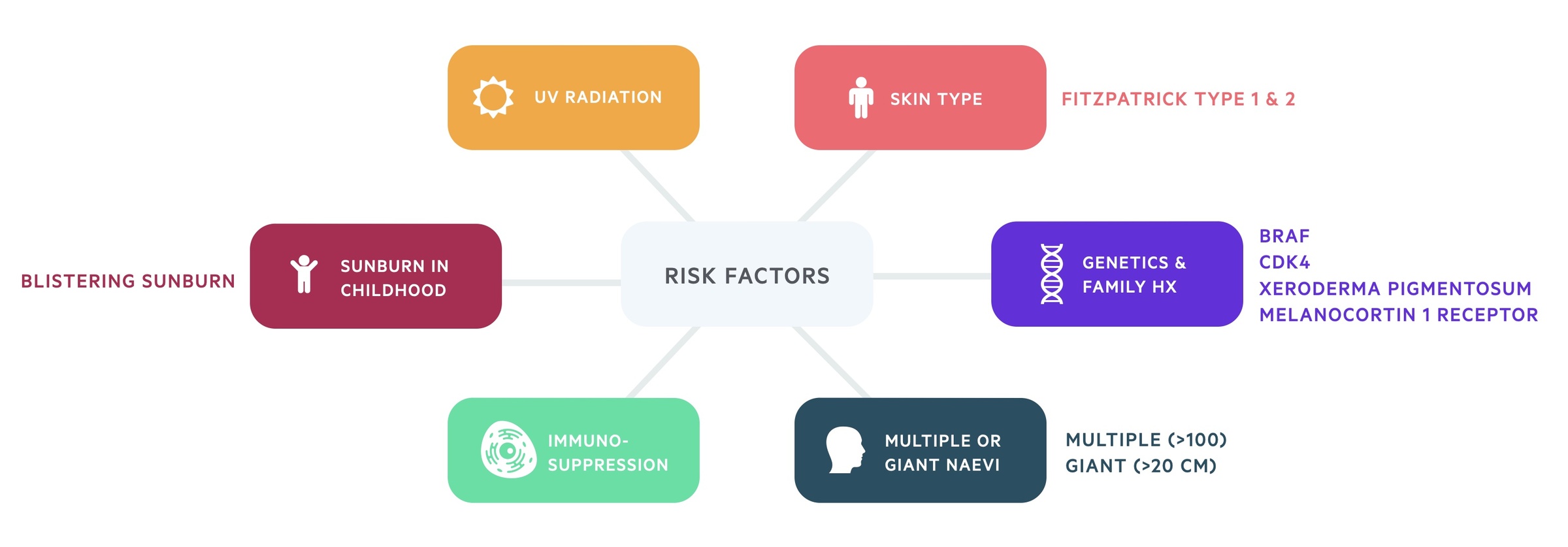

Melanoma results from a combination of environmental and genetic factors.

Exposure to UV light constitutes the predominant environmental factor for most types of melanoma (although it is thought to play less of a role in acral lentiginous melanoma - see sub-types).

Other risk factors include:

- Severe sun burn in childhood (e.g. blistering)

- Immunosuppression

- Multiple (>100) or giant (>20 cm) naevi

- Skin type (Fitzpatrick Skin types I & II)

- Family history (cyclin-dependent kinase mutations are linked to 20-40% of familial melanoma)

- Genetic mutations (CDK4, xeroderma pigmentosum, melanocortin 1 receptor)

Epidemiology

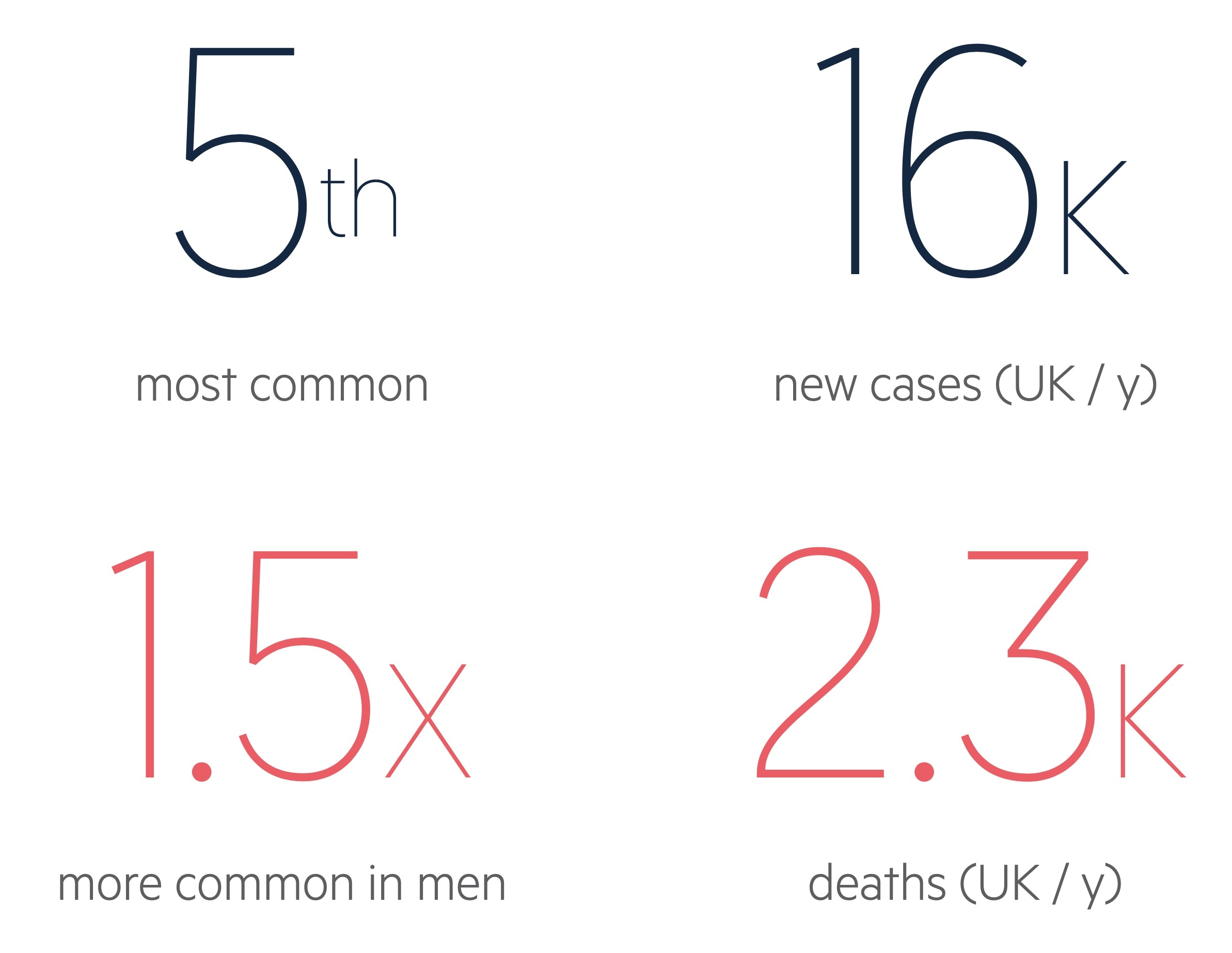

In the UK, melanoma represents the fifth most common cancer.

In the UK, there are over 16,000 new cases of melanoma per year. Here, it represents the fifth most common cancer, accounting for 4% of all new cancers. Since the early 1990’s, incidence has more than doubled. Incidence is increasingly more rapidly in men than women.

Melanoma is 1.5 x more common in men than women. Distribution also differs between sexes. In men, lesions tend to occur on the trunk, whilst in women, the arms and legs are more commonly affected.

Sadly, melanoma accounts for approximately 2,300 deaths per year in the UK.

Skin types

Melanoma is one of the commonest cancers in light-skinned populations, but can also occur in those with darker skin.

Melanoma predominately affects light-skinned populations, but can occur in black, asian or hispanic populations too. In these groups, some evidence suggests melanoma may be being diagnosed at a later stage, and consequently, may carry a worse prognosis (Mahendraraj et al, 2017).

Potential reasons for this may include:

- Reduced public awareness - public perception is that dark-skinned populations are at much lower risk of melanoma, and from the effects of UV-radiation in general.

- Lower index of suspicion - healthcare providers may be falsely reassursed by the perceived lower incidence in these groups. Darker spots may go unnoticed or mis-daignosed as fungal infections or from trauma.

- Detection may be more challenging - acral lentingious melanomas, for instance, are more common in darker skinned populations (accounting for approximately half of melanoma cases, compared to 1 in 20 among white groups). Acral melanomas tend to occur in less sun-exposed 'out of the way' areas such as the soles of the feet, under nails or on the palms of the hands.

An acral melanoma on the foot of a person with darker skin

Image courtesy of dermnetnz.org

Pathophysiology

Melanoma originates from uncontrolled proliferation of melanocytes in the basal epidermis.

Melanocytes are specialised melanin-producing cells that are found within the basal epidermis (the deepest layer of the epidermis). The melanin produced is transferred to the mitotically-active keratinocytes above. Here, it protects the nucleus of keratinocytes from UV damage.

Typical tumour progression

- Benign naevus (typical mole) - controlled proliferation of melanocytes

- Dysplastic naevus (atypical mole) - abnormal proliferation of melanocytes resulting in a pre-malignant lesion with atypical cellular structure.

- Radial growth phase - melanomas tend to extend superficially and outwards initially. Melanocytes acquire the ability to proliferate horizontally in the epidermis, but few cells invade the papillary dermis.

- Vertical growth phase - malignant cells invade the basement membrane and proliferate vertically downwards into the dermis.

- Metastasis - malignant cells may spread to other areas of body. Typically they travel to regional lymph nodes first; but they may spead to other areas of the skin / soft tissue, or to solid organs (such as the lungs, liver, bone or brain).

Clinical features

Melanoma usually appears as a pigmented lesion with an irregular border with a tendency to grow or change.

Melanomas mostly arise de novo. However, rarely they can occur within an existing lesion (e.g. from a congenital naevus).

ABCDE criteria

Previously, melanomas were often diagnosed at a late stage. The need to detect melanomas early lead to the development of the ABCDE criteria (American Association of Dermatologists):

- A - Asymmetry

- B - Border irregularity

- C - Colour alterations

- D - Diameter > 6 mm

- E - Evolution

These simple criteria enable individuals and non-specialised healthcare professions to differentiate common pigmented lesions from suspicious ones.

Dermoscopy

Dermoscopy is the examination of suspicious skin lesions with a dermatoscope (a small, hand-held microscope).

Biopsy

For suspicious lesions, patients are typically referred for an excisional biopsy.

An excisional biopsy is a procedure in which the suspicious lesion is completely excised with a margin of 1-2 mm of healthy surrounding skin. The sample includes a portion of subcutaneous fat - ensuring that the full-thickness of the dermis has been sampled. The procedure is usually perfumed under local anaesthetic as a day case. During the procedure, particular care should be taken not to cause trauma to the specimen (this can inadvertently alter the histological grading).

Orientation of the biopsy incisions must take into account the potential need for subsequent larger excisions. For example, longitudinal incisions are typically preferred on the limbs.

Occasionally, a punch or incisional biopsy (in which a small sample of the lesion is taken) may be performed. This is often reserved for particularly large lesions, or for those lesions in close proximity to vital structures (e.g. ears, eyes, nose).

Subtypes

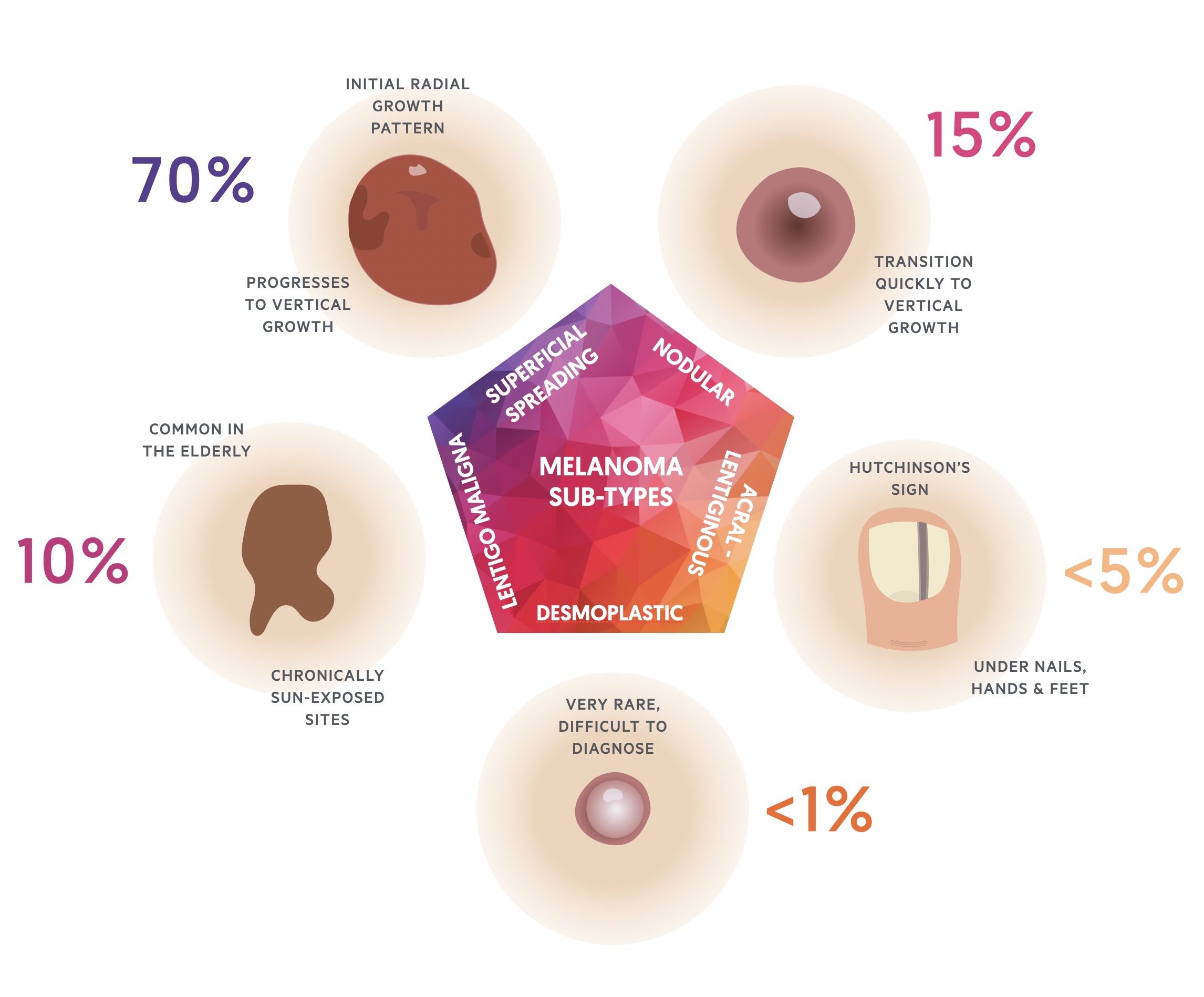

Histologically, melanomas are divided into five major subtypes.

- Superficial spreading (70%)

- Nodular (15%)

- Lentigo maligna (10%)

- Acral lentiginous (<5%)

- Desmoplastic melanoma (<1%)

Amelanotic melanoma is a form of melanoma in which the malignant cells possess little or no pigment. They are classically described as 'skin coloured'. Any subtype of melanoma can be amelanotic.

1. Superficial spreading

Superficial spreading melanoma is the most common; accounting for around 70% of melanomas.

Can occur in any location. Characterised by an initial radial growth pattern, which in the later stages of the disease, progresses to invade deep into the dermis (vertical growth).

A typical SSM in a person with darker skin.

Image courtesy of dermnetnz.org

2. Nodular

Nodular melanoma is the second most common; they are typically more seen at a more advanced stage.

They transition immediately into the vertical growth phase. Because of this, it is usually diagnosed at a more advanced stage.

3. Lentigo maligna

Lentigo maligna melanoma occurs in the elderly on chronically sun-exposed sites.

Accounts for around 10% of melanomas. Characterised by long period of intraepithelial growth (slow), therefore usually better prognosis.

4. Acral lentiginous melanoma

Typically occurs under nails, or on the palmar / plantar surfaces of hands and feet.

Much less common (< 5%). Diagnosis is often delayed, especially for subungal lesions (commonly mistaken for traumatic haematomas)

5. Desmoplastic melanoma

A very rare form of melanoma, characterised histologically by abnormal deposits of collagen.

Often histologically very difficult to diagnose. Frequently mistaken for other tumours with collagen deposits including schwannomas and fibrohistiocytic tumours. Up to 50% of these lesions are amelanotic.

Histology

Clark level, Breslow thickness, ulceration and mitotic index may be used to classify the depth of melanoma invasion and / or give an indication of prognosis.

Clark level (I-V)

A histological classification with estimated prognosis based upon the anatomical level of invasion into the skin.

Formulated by Clark in 1969. Highlighted for the first time the prognostic significance of depth of invasion. However, the system has been a source of continuous debate, particularly among pathologist. It has now effectively lost its relevance in recent years.

Breslow thickness (mm)

Breslow thickness (BT) is based on the vertical thickness of the tumour in millimetres.

Proposed by Breslow in 1970. The Breslow thickness is measured from the stratum granulosum of the epidermis, or if the lesion is ulcerated, from the bottom of the ulceration upwards to the point of maximum infiltration. Breslow thickness appears to correlate strongly with mortality.

Ulceration

The presence or absence of ulceration is important.

Ulceration is defined as the absence of intact epithelium overlying the lesion. Ulceration correlates with poorer prognosis. It is suggestive of an aggressive tumour phenotype with greater likelihood for invasion and metastasis.

Mitotic index

Mitotic index (an indicator of cell turnover) is also an important histological finding.

Expressed as the number fo mitoses per mm2 in the invasive component of the melanoma.

Investigations

All patients require a careful skin and lymph node examination.

In cases of a clinically suspicious lymph node, fine needle aspiration (FNA) and cytology should be performed, this is typically undertaken within the outpatient clinic.

There is emerging consensus on the role of total body CT or PET-CT for high-risk lesions. Patients at high-risk for distant metastasis include those with aggressive lesions (pT4, ulcerated, high mitotic index etc.) or the presence of known lymph node spread.

LDH (lactate dehydrogenase - a blood marker of cell turnover) is useful for risk stratifying.

Staging

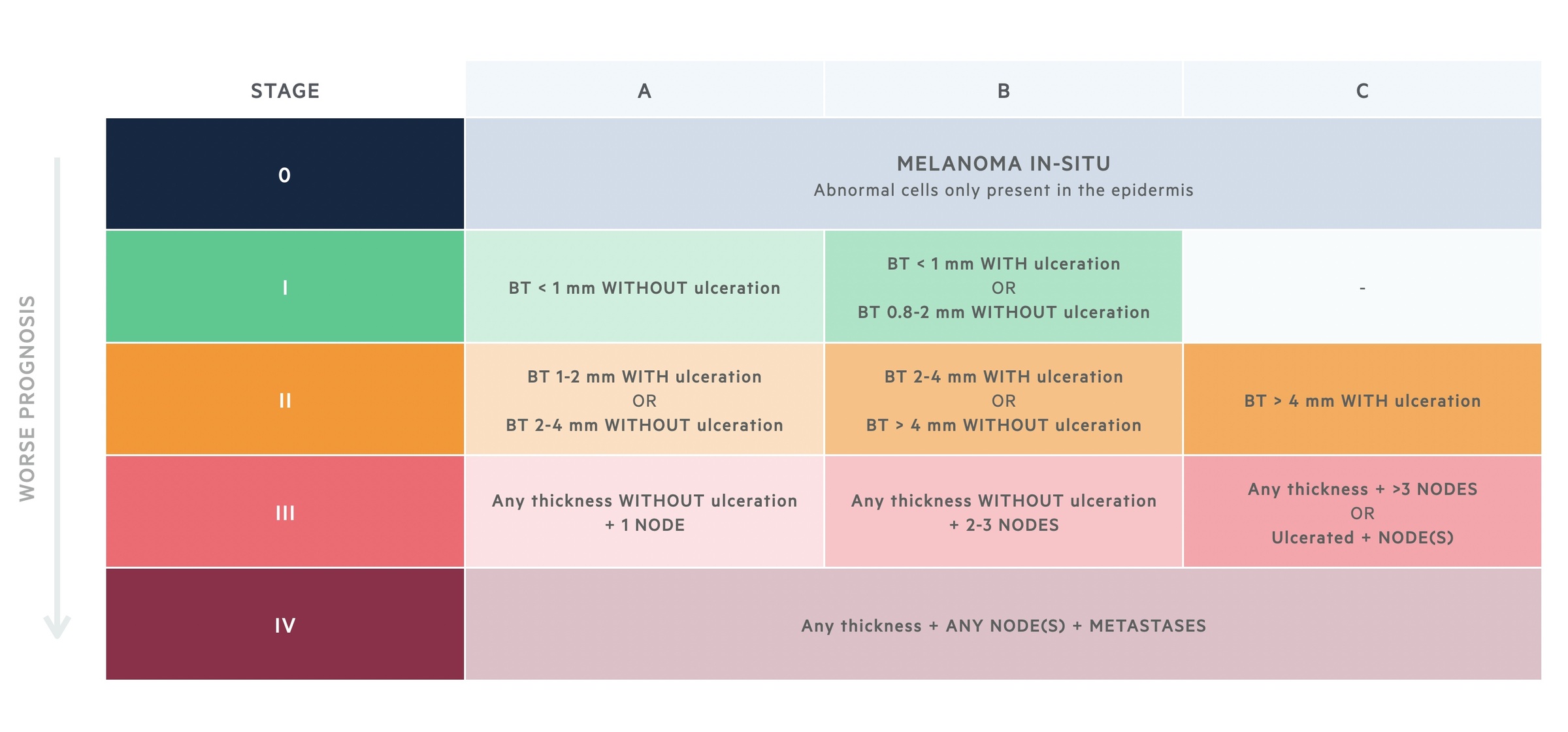

The staging system used for melanoma is the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) system.

Staging

The stage of a cancer is used to describe the size and depth of the melanoma, and whether it has spread. This is based on the tumour, node, metastasis (TNM) system.

- Tumour - Breslow thickness (mm) +/- presence of ulceration.

- Node - whether the melanoma has spread to the lymph nodes and how many.

- Metastases - presence of spread to other parts of the body.

AJCC staging

Most specialists utilise the AJCC cutaneous melanoma staging guidelines (8th edition, 2018).

Stage 0 - ‘melanoma in-situ'

Abnormal cells are only present in the top layer of skin (the epidermis) and have not spread to the dermis.

Stage I

- IA - melanoma is less than 0.8mm thick WITHOUT ulceration.

- IB - melanoma is less than 0.8mm thick WITH ulceration OR 0.8-1mm thick +/- ulceration; OR melanoma is 1-2mm thick WITHOUT ulceration.

Stage II - usually thicker than stage I but have not spread.

- IIA - melanoma is 1-2mm thick WITH ulceration; OR melanoma is 2-4mm thick WITHOUT ulceration

- IIB - melanoma is 2-4mm thick WITH ulceration; OR melanoma is >4mm thick WITHOUT ulceration

- IIC - melanoma is >4mm thick WITH ulceration

Stage III - lymph node involvement.

- IIIA - any thickness WITHOUT ulceration + 1 postivie node.

- IIIB - any thickness WITHOUT ulceration + 2-3 postivie nodes.

- IIIA - any thickness WITHOUT ulceration + >3 postivie nodes OR any thickness WITH ulceration + ANY postive nodes.

Stage IV - metastatic spread.

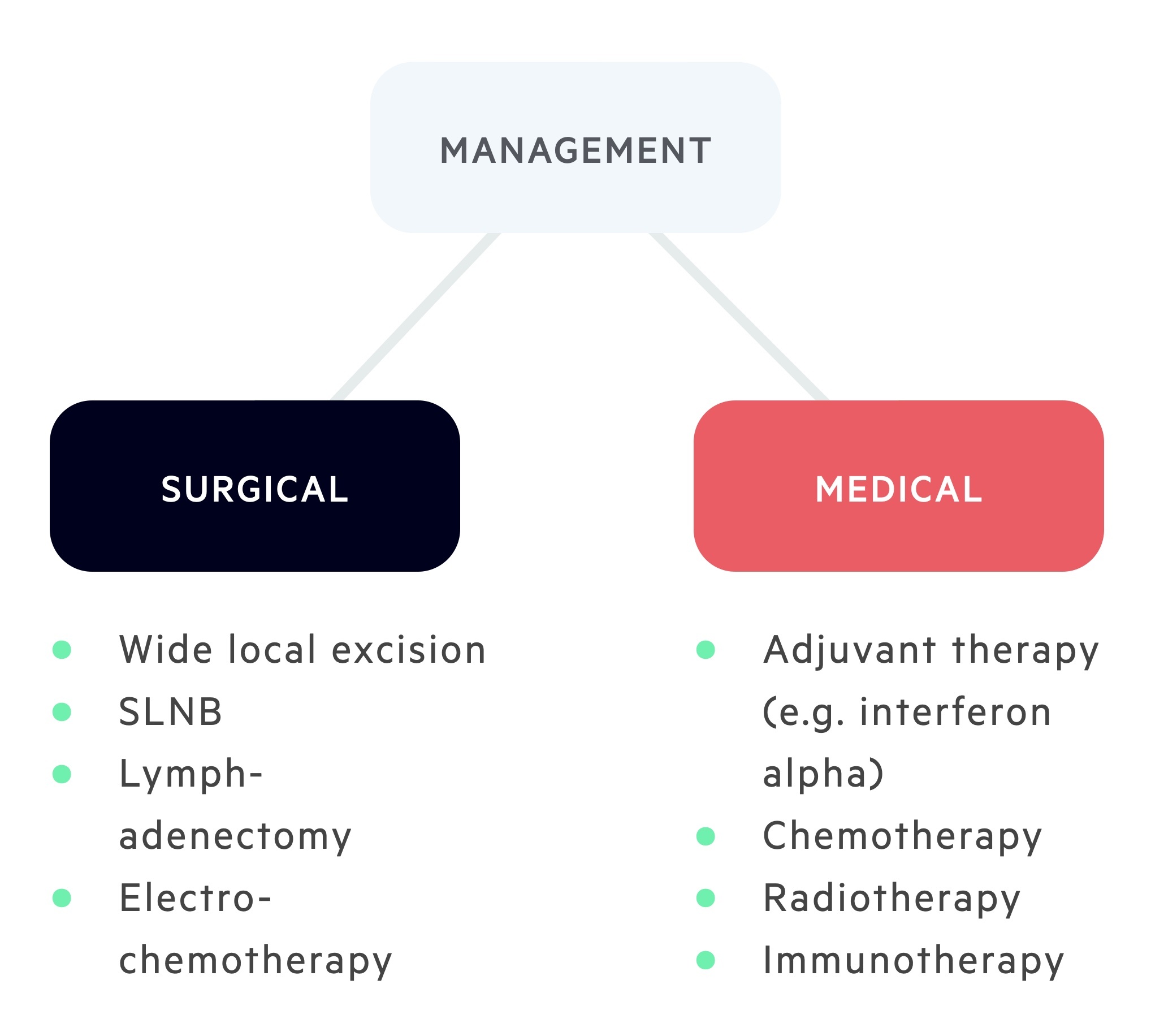

Management

Management is complex and guided by the Melanoma Multidisciplinary Team (MDT).

Wide local excision (WLE)

WLE represents the standard treatment for primary melanoma. Involves removal of the biopsy scar with a surrounding margin of ‘healthy’ skin, with fat, down to muscular fascia. This margin is determined by the Breslow thickness.

In clinical practice, a 30 mm excision margin is rarely performed.

Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy (SLNB)

The role of SLNB in melanoma is unclear. NICE guidelines suggest use of SLNB as a staging tool. The principle is that the first lymph node that receives drainage from an affected area is denoted the ‘sentinel node’.

A SLNB is typically performed under general anaesthetic, usually at the same-time as the WLE.

Typically, on the morning of surgery, a radio-labeled tracer is injected into the old biopsy scar. A CT scan is then performed which identifies ‘hot spots’. This allows the surgeon to plan the procedure, as there may be multiple drainage basins.

On the operating table, once anaesthetised, a blue dye is injected into the biopsy scar. A hand-held gamma probe is then used to identify the ‘hot spots’ (these are correlated with the radiological imaging). Incisions are planned over these areas. During the operation, the surgeon identifies the target lymph node(s), they appear 'hot' and 'blue'. Targeted lymph nodes are excised and sent for histological analysis. Typically only a small number of lymph nodes are excised in order to minimise the risk of subsequent lymphoedema.

A postitive SLNB (i.e. disease deposits found within the sentinel lymph nodes) usally results in referral for a subsequent lymphadenectomy (lymph node clearance), in which all of the regional lymphatics are removed. A lymphadenectomy is performed in an attempt to gain regional control of disease.

Electrochemotherapy

Electrochemotherapy is a relatively new therapy for patients with locally advanced melanoma.

It is used to treat melanoma metastases in the skin using pulses of electricity together with chemotherapy.

A chemoherapeutic agent is given either intravenously or injected directly into the tumour. Short, powerful pulses of electricity are then applied to the tumour. The electrical energy transiently increases the permeability of the tumour cell membranes, allowing the chemoherapeutic agent to pass through more effectively.

Adjuvant therapy

Adjuvant therapy is considered in some patients after surgical excision of melanoma.

It comprises a number of modalities:

- Chemotherapy

- Radiotherapy

- Immunotherapy

Last updated: October 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback