Hepatocellular carcinoma

Notes

Overview

Hepatocellular carcinoma is a primary liver cancer that occurs most commonly in patients with cirrhosis.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the major complications of cirrhosis and chronic hepatitis B. It is a primary liver malignancy that is often diagnosed late with poor prognosis.

Cancers affecting the liver may be primary or secondary:

- Primary: cancer initiated in the liver. Commonly due to HCC or cholangiocarcinoma.

- Secondary: cancer that started somewhere else but metastasised to the liver.

Early recognition and treatment of HCC is crucial to improve survival. The five year survival with early disease is as high as 90%, but with advanced disease the median survival is < 4 months. Ultrasound surveillance forms an important part of practice in the long-term management of patients with cirrhosis.

Epidemiology

Worldwide, HCC is one of the leading causes of cancer-related death.

HCC is a frequently diagnosed malignancy associated with significant mortality. In 2020, the global cancer observatory recorded that liver cancer, of which HCC is the predominant type, was the sixth most frequently diagnosed cancer and third leading cause of cancer-related deaths.

The incidence of liver cancer is highest in Asia due to the burden of viral hepatitis. Chronic hepatitis B increases the risk of HCC even in the absence of cirrhosis. In Western Europe, the incidence of liver cancer is 8.6 per 100,000 and 2.6 per 100,000 in males and females, respectively. This reflects the male predominance of HCC with a male-to-female ratio of approximately 3:1.

Risk factors

HCC is uncommon in the absence of cirrhosis.

Cirrhosis is a major risk factor for developing HCC. In the absence of cirrhosis, HCC is uncommon and usually associated with risk factors including chronic hepatitis B or non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

Cirrhosis

Cirrhosis of any aetiology increases the risk of HCC. Up to one third of patients with cirrhosis will develop HCC during their lifetime. This is why surveillance is so critical (discussed below).

Hepatitis B virus

Hepatitis B increases the risk of developing HCC even in the absence of cirrhosis. The annual incidence of HCC in patients with chronic hepatitis B and cirrhosis is 3.2 cases per 100 person-years compared to 0.1 cases per 100 person years in patients without cirrhosis. For more information see our notes on Hepatitis B.

Hepatitis C virus

In patients with hepatitis C, HCC is usually seen in patients with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis. The increased risk of HCC remains even if patients are treated for hepatitis C. For more information see our notes on Hepatitis C.

Other risk factors

- Hepatitis D

- Aflatoxin (B1): a mycotoxin produced by certain moulds. Can contaminate food products.

- Betel nut chewing: fruit of the areca palm. Chewed widely across Asia for its stimulant properties

- Alcohol: causes cirrhosis and acts synergistically with other risk factors to increase risk of HCC

- Smoking

- Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: increasingly recognised contributor to HCC, particularly in Western countries

- Genetic susceptibility: alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency, hereditary haemochromatosis.

Aetiology & pathophysiology

The major predisposing factor to developing HCC is cirrhosis of the liver.

The most prominent factors associated with development of HCC are chronic viral hepatitis (B/C), chronic alcohol consumption, aflatoxin contaminated food and essentially any factor that predisposes to cirrhosis. Each factor leads to chronic liver injury that promotes necrosis (cell death) followed by hepatocyte regeneration. These processes culminate in regenerative nodules and cirrhosis, which refers to irreversible liver scarring.

These areas of regenerative nodules can lead to hyperplasia (increased cell proliferation), which then leads to dysplasia (abnormal cell growth) and eventually malignancy (i.e. HCC). Depending on the aetiological factor, several mechanisms can promote HCC development including alteration to the microenvironment, chronic inflammation, oxidative stress and ultimately multiple genetic mutations that promote cell growth and increase cell survival. One of the key genes mutated in HCC is TP53, which is a crucial tumour suppressor gene.

The fact that chronic hepatitis B can lead to HCC in the absence of cirrhosis may stem from its ability to integrate its own DNA material into the host genome and promote replication.

Clinical features

There are a wide range of clinical presentations of HCC.

Many patients with HCC may be asymptomatic and the lesion picked up incidentally during ultrasound surveillance. If symptomatic, patients may present in variety of ways including constitutional symptoms of malignancy, localised symptoms, decompensated cirrhosis or paraneoplastic syndromes.

Constitutional symptoms

These refer to the global, non-specific symptoms that are often associated with underlying malignancy, infection or systemic inflammatory disorders.

- Fever

- Anorexia

- Night sweats

- Weight loss

- Fatigue

Localised symptoms

Patients may experience symptoms localised to the tumour depending on its size and compression of nearby structures.

- Abdominal pain

- Hepatomegaly

- Right upper quadrant mass

- Jaundice (due to obstruction of the biliary tree)

Sudden onset abdominal pain and haemodynamic instability may be suggestive of intraperitoneal bleeding due to tumour rupture.

Features of chronic liver disease

HCC commonly occurs in the setting of cirrhosis and patients may have underlying features of chronic liver disease. For further information see our notes on Chronic liver disease.

HCC may be a cause of decompensation due to tumour growth and obstruction of hepatic and portal veins. This can lead to ascites and GI bleeding. Other features of decompensation may be present including encephalopathy, jaundice and coagulopathy.

Paraneoplastic syndromes

This refers to the non-metastatic manifestations of malignancy. A variety of syndromes may occur, which usually indicate a poor prognosis.

- Hypoglycaemia: often due to the tumours high metabolic rate. Rarely due to secretion of insulin-like growth factor.

- Erythrocytosis: increased red blood cell production due to secretion of erythropoietin (EPO).

- Hypercalcaemia: secretion of parathyroid-hormone related peptide.

- Dermatological conditions (e.g. dermatomyositis).

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of HCC may be based on imaging criteria alone in the context of cirrhosis.

There are two ways to make a formal diagnosis of HCC:

- Imaging: specific criteria for HCC can be used in patients with cirrhosis.

- Histology: required in patients without cirrhosis. May be needed in equivocal cases with cirrhosis.

Imaging

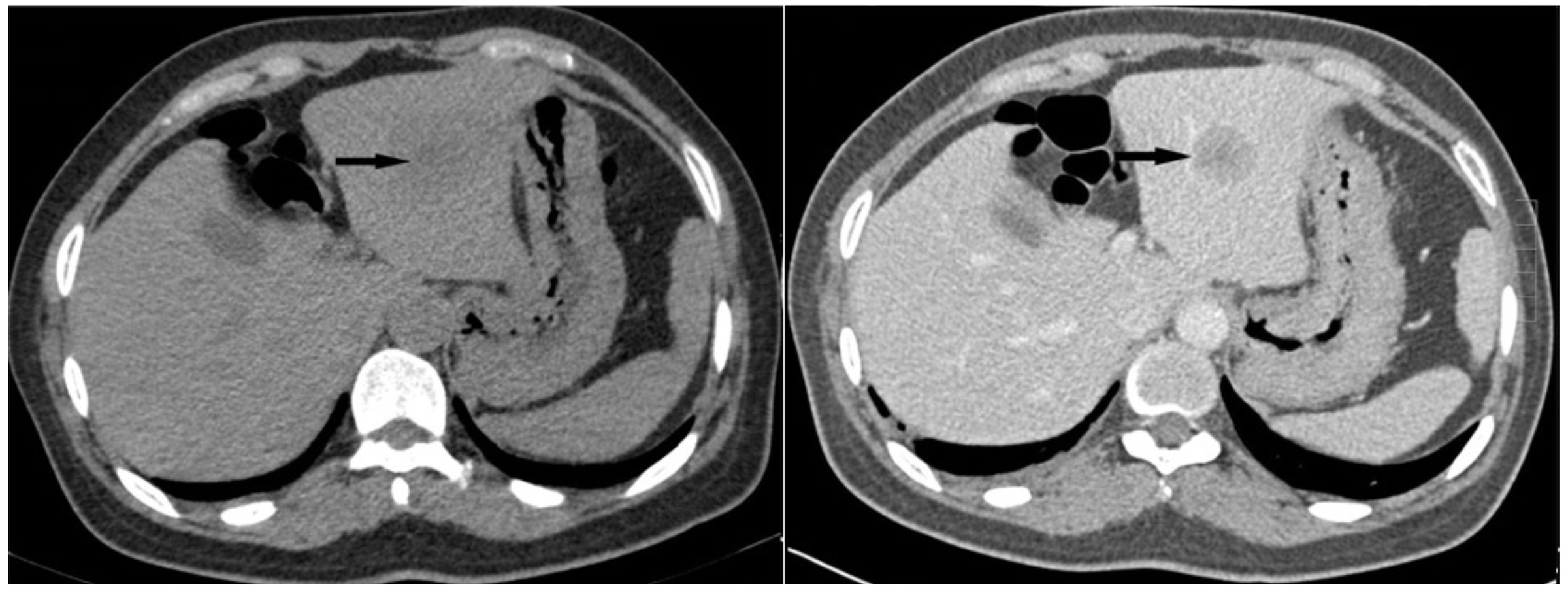

In patients with cirrhosis, a formal pathological diagnosis taken by biopsy or surgical specimen is not required for the diagnosis. There are specific CT or MRI imaging criteria (e.g. Liver Imaging Reporting and Data System) that can be used to make a diagnosis of HCC.

Diagnosis is usually confirmed in nodules that are > 1cm with typical vascular features (hypervascularity in the arterial phase with washout in the portal venous or delayed phase). In unclear cases, a liver biopsy and histology may be required. There is no role for measuring alpha-fetoprotein (AFP).

Non-contrast and contrast CT of a HCC in the left lobe of the liver

Imaging courtesy of Zhenyu Pan et al (Wikimedia commons)

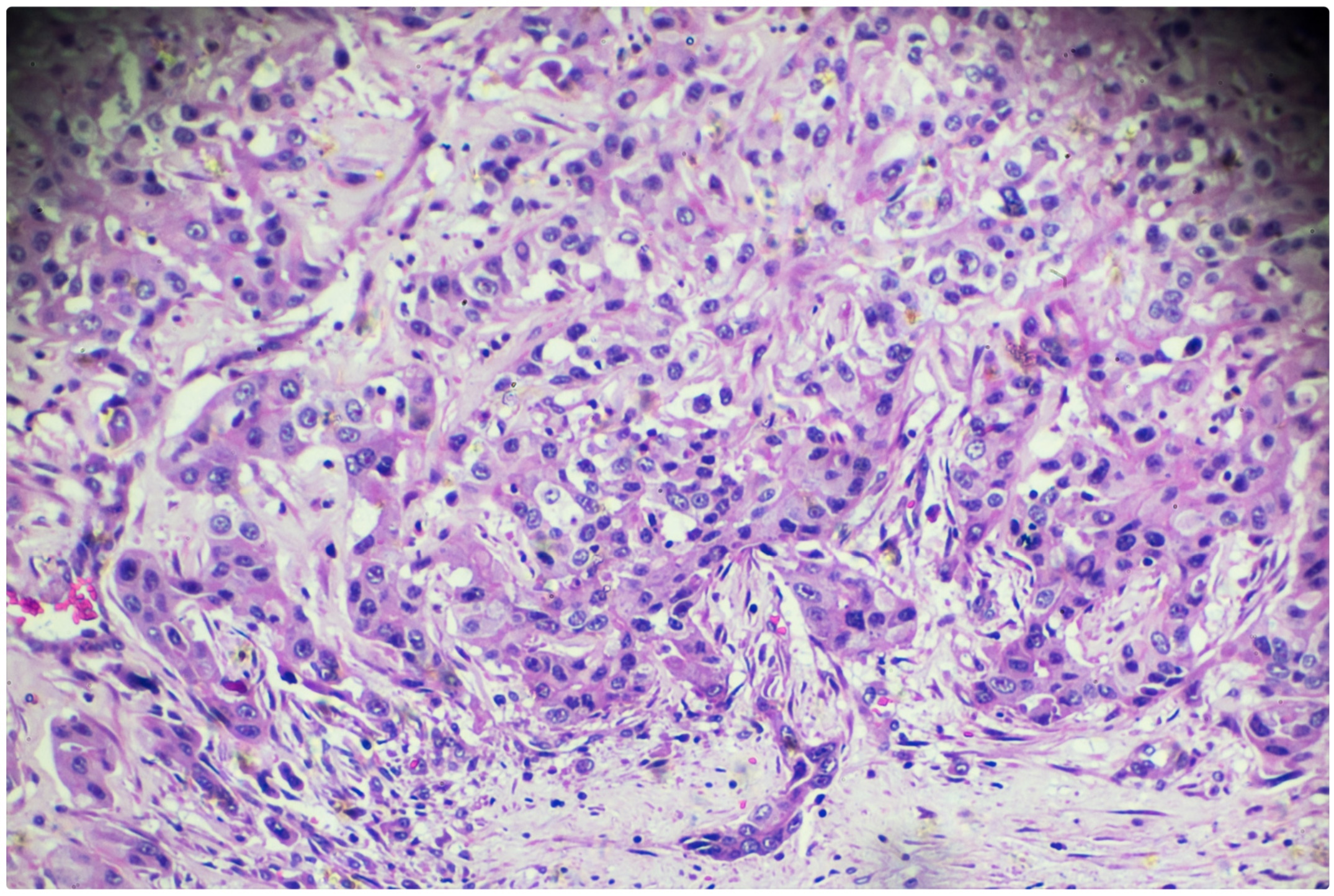

Histology

A pathological sample obtained by liver biopsy or surgical specimen can be used to make a diagnosis of HCC. This is required in any patient with a suspected HCC in the absence of cirrhosis. Special stains may be added to the histological sample to differentiate between hepatocellular and cholangio-carcinoma. On rare occasions there may be features of both (mixed tumours).

Rare complications from attempting to obtain a sample using liver biopsy include bleeding and needle track seeding. Needle tract seeding refers to implantation of tumour cells along the tract created by an instrument when attempting to take a sample.

Histology of a hepatocellular carcinoma

Work-up

Patients with suspected, or confirmed, HCC require a full diagnostic work-up to help determine treatment options.

In addition to confirmation of the diagnosis using imaging or histology, patients require a full work-up that includes:

- Clinical assessment: determine risk factors for chronic liver disease, features of chronic liver disease and performance status.

- Aetiology of liver disease: determine using a non-invasive liver screen and laboratory analysis.

- Severity of liver disease: includes assessment of portal hypertension.

- Staging: refers to determination of the size of the primary tumour and extent of spread.

Clinical assessment

The majority of HCCs occur on a background of cirrhosis, which may be identified for the first time when HCC is diagnosed. It is important to determine any risk factors for chronic liver disease (e.g. alcohol intake, intravenous drug use), features of chronic liver disease on examination (i.e. ‘stigmata of chronic liver disease’) and performance status.

Performance status essentially refers to the ‘fitness’ of a patient. It is a measure of how well a person can carry out ordinary daily activities and gives an estimate of what treatments a patient may tolerate. Performance status is graded 0-5 based on the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) scale.

Aetiology of liver disease

A full non-invasive liver screen is essential to determine the underlying cause of liver disease. This includes a full laboratory panel, liver imaging, and specialist blood tests. For more information see our notes on Chronic liver disease.

Severity of liver disease

It is important to determine the severity of liver disease as this may alter treatment options. Severity is usually based on the Child-Pugh scoring system that takes into account bilirubin, serum albumin, ascites, prothrombin time and hepatic encephalopathy. Other systems include the United Kingdom Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (UKELD) or Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD).

The degree of portal hypertension, which is one of the major complications of cirrhosis, is also important to determine. Clinically significant portal hypertension may warrant invasive assessment of hepatic-venous pressure gradients. Based on the Baveno VI criteria, clinically significant portal hypertension is unlikely if the platelet count is > 150 x 109 cells/L and a non-invasive liver stiffness measurement is < 20 kPa.

Staging

In oncology, staging refers to assessment of the size of the primary tumour and extent of spread. It helps to work out how advanced a cancer is and guides treatment options. There are different staging systems that can be used, which rely on imaging (e.g. CT/MRI). The most widely recognised is the tumour, node, metastasis staging system known as ‘TNM’.

In HCC, there are various staging systems that can be used. One widely used is the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) system. Discussed further below.

BCLC

The Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging system is used to guide treatment in patients with HCC.

The BCLC staging system is used to guide treatment options. It takes into account tumour stage (i.e. size and spread), liver function (based on Child-Pugh score) and performance status (ECOG 0-5). Patients with early stage disease (0-A) may be amenable to locoregional therapy (e.g. resection, percutaneous ablation or transarterial therapies) or transplantation.

BCLC is divided into five stages:

- 0 (very early): Performance status 0, Child-Pugh A, single tumour < 2cm

- A (early): Performance status 0, Child-Pugh A-B, single tumour or up to 3 nodules ≤ 3 cm

- B (intermediate): Performance status 0, Child-Pugh A-B, multinodular tumours

- C (advanced): Performance status 1-2, Child-Pugh A-B, tumour with portal invasion or extrahepatic spread

- D (terminal): Performance status >2, Child-Pugh C (decompensated liver disease)

Management

Numerous therapies may be offered to patients with HCC based on BCLC staging.

There are a variety of treatment options that can be offered for HCC. These are guided by BCLC staging.

- Locoregional therapies: liver resection, percutaneous ablation, transarterial therapies

- Liver transplantation

- Systemic therapy: multikinase inhibitors (e.g. Sorafenib), others.

- Other therapies: radiotherapy, brachytherapy, immunotherapy

- Best supportive care

Locoregional therapies

Locoregional therapies form the basis of HCC treatment in patients with early stage disease (0-A).

There are three major types of treatment:

- Liver resection: surgical resection of the liver with the area of HCC. Requires good liver function and enough liver to be left after resection to prevent post-hepatectomy liver failure (i.e. the remnant liver is inadequate to carry out usual function). There is significant risk of tumour recurrence following resection.

- Percutaneous ablation: involves thermal ablation of the tumour by radiofrequency (RFA) or microwaves (MWA). Can be used as a curative option in early stage disease. RFA is commonly performed percutaneously with insertion of a needle into the tumour and subsequent generation of frictional heat that destroys tumour cells. Similar outcomes to liver resection.

- Transarterial therapies: this involves passing a catheter through the arterial system (i.e. femoral artery puncture) towards vessels that supply the tumour. From this point, chemotherapy alone or in combination with other agents (e.g. lipiodol or embolising agents such as coils) can be injected into the vessel. This helps destroy the cancer cells and blocks the tumours blood supply. Transarterial chemoembolisation (TACE) is a common technique that may be used in stage 0-B HCC and can be used as a bridge to transplantation. Treatment with TACE may be repeated.

Liver transplantation

Liver transplantation can be offered to some patients with early stage HCC. It is a potentially curative option for both the HCC and underlying liver disease. However, there are strict selection criteria.

The Milan criteria is used to determine which patients would benefit from liver transplantation. It has three components:

- Tumour size: A single lesion < 5 cm, OR, up to 3 lesions each < 3cm

- Invasion: no evidence of macrovascular invasion

- Other features: No extrahepatic features

Patients who meet the Milan criteria have a < 10% recurrence rate and 5-year survival of 70%. Patients meeting these criteria should be assessed at transplant centre for suitability of transplantation that requires a comprehensive assessment. Other more liberal criteria are available including the University of California San Francisco criteria. If accepted for transplantation, some patients may have to wait a long time on the transplant waiting list (i.e. > 3 months). These patients may be offered a ‘bridging’ therapy such as TACE.

Systemic therapy

In patients with more advanced disease (Stage C), systemic therapies may be offered, which include multikinase inhibitors (e.g. Sorafenib). Systemic therapy may also be offered to patients with intermediate disease who are not suitable for locoregional therapies.

Sorafenib inhibits tumour cell angiogenesis and proliferation through inhibition of multiple tyrosine kinase receptors that are involved in key signalling pathways (e.g. BRAF, VEGFR, PDGFR). It is an oral therapy that shows a survival benefit compared to placebo with a median survival of around 10.7 months. Key side-effects include hand and foot skin reactions, diarrhoea, high blood pressure, and nausea. Treatment needs to be reduced or withdrawn in up to 50%.

Other systemic therapies include:

- Lenvatinib (multikinase inhibitor)

- Regorafenib (multikinase inhibitor)

- Cabozantinib (small molecule inhibitor against multiple targets including RET, VEGFR2)

- Ramucirumab (monoclonal antibody that targets VEGFR2)

Other therapies

A variety of additional therapies may be used in the treatment of HCC including radiotherapy, brachytherapy and immunotherapy. Immuntherapies are an emerging group of drugs used in a variety of cancers that alter the immune response to control malignancy. These additional therapeutic options are beyond the scope of these notes.

Best supportive care

This refers to management of a patients symptoms without the aim of treating the underlying cancer. Palliative care usually have an active role in best supportive care to help address a patients physical, psychological and spiritual issues as they arise.

Generally, patients with a poor performance status or decompensated liver disease (i.e. Child-Pugh C) are only offered best supportive care. The benefit of systemic therapy in patients with decompensated liver disease has not been established.

Surveillance

Patients with cirrhosis should be offered HCC surveillance with abdominal ultrasound.

Patients with cirrhosis are high risk of developing HCC. The risk differs across aetiologies. In any patient with cirrhosis, surveillance with ultrasound imaging should be offered as part of a HCC surveillance programme.

Surveillance is carried out by abdominal ultrasound every 6 months with or without serum AFP. If a new HCC is suspected, patients require more detailed imaging (e.g. CT/MRI) and discussion at the HCC multi-disciplinary meeting.

Prognosis

In HCC, the overall 5-year survival is poor.

Staging is useful to determine the overall survival in malignant disease. In HCC, the different staging systems can be used to guide prognosis. Here we demonstrate survival (without treatment) based on BCLC staging:

- Stage 0-A: > 5 years

- Stage B: > 2.5 years

- Stage C: > 1 year

- Stage D: ~ 3 months

The overall 5-year survival for all stages of HCC is poor at only 15%.

Last updated: November 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback