Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia

Notes

Introduction

Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia is the most common malignancy of childhood.

Leukaemia

Leukaemia refers to a group of malignancies that arise in the bone marrow. They are relatively rare but together are the 12th most common cancer in the UK, responsible for around 9,900 cases and 4,700 deaths a year.

There are four main types:

- Acute myeloid leukaemia (AML)

- Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL)

- Chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML)

- Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL)

Presentation, prognosis and management all depend on the type and subtype of leukaemia.

Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia

ALL arises from a clone of lymphoid progenitor cells that undergo malignant transformation. Most are B-cell in origin though ALL may arise from T-cell precursors.

As clonal expansion occurs lymphoid precursors replace other haematopoietic cells in the bone marrow. With time, infiltration into other body tissues occurs.

Epidemiology

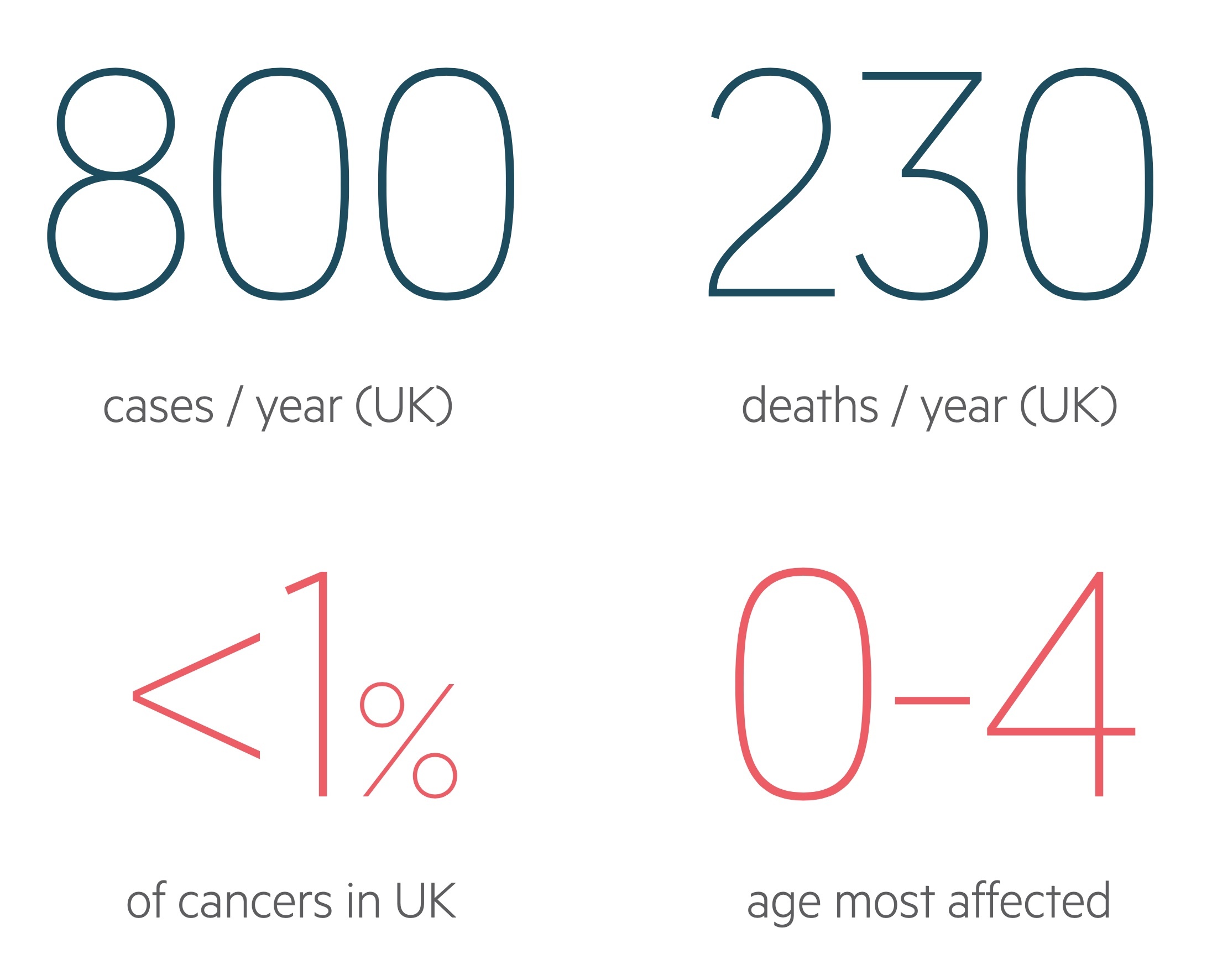

There are approximately 800 cases of ALL in the UK each year.

ALL is rare accounting for less than 1% of all cancers and causing approximately 250 deaths in the UK each year. It may occur at any age but is more common in early childhood with incidence peaking in those aged 0-4.

Figures from Cancer Research UK (last accessed Nov 2021).

Aetiology and pathophysiology

The causes of ALL are still poorly understood.

It is thought to often result from a combination of genetic susceptibility and environmental exposure. Infection (in particular with viruses) may well act as a triggering event.

ALL occurs due to the proliferation of malignant lymphoid progenitor cells in the bone marrow. Broadly it can be classified as:

- B cell lineage (majority)

- T-cell lineage

Proliferating malignant cells replace normal lines of haematopoietic cells resulting in their suppression. This leads to anaemia, thrombocytopenia (low platelets) and neutropenia (low neutrophils). See our haematopoiesis notes for more on the normal process.

Infiltration and proliferation are not limited to the bone marrow. It may affect other body tissues, especially lymph nodes, the liver and the spleen.

Cytogenetic features

- t(12;21): the most common translocation seen in ALL affecting children. Results in TEL-AML fusion gene.

- t(9;22): known as the Philadelphia chromosome, seen in around 33% of adults and 2-5% of children. Associated with a poor prognosis. Results in BCR-ABL fusion gene.

- t(4;11): common in infants < 12 months but rare in adults. Results in the MLL-AF4 fusion gene.

- Hyperdiploid karyotype: seen in 30-40% of children, less common in adults.

- Hypodiploid karyotype: may also be seen, associated with a poor prognosis.

Clinical features

Patients often present with a short history of features consistent with marrow suppression or lymphadenopathy

ALL may present with a number of features. It can be helpful to categorise them by their underlying aetiology.

Marrow failure

- Anaemia:

- Fatigue

- Breathlessness

- Angina

- Neutropenia:

- Recurrent infections

- Thrombocytopenia:

- Petechiae

- Nose bleeds

- Bruising

Tissue infiltration

The involvement and proliferation of lymphoid progenitors in body tissues is often clinically apparent at diagnosis:

- Lymphadenopathy

- Hepatosplenomegaly

- Bone pain

- Mediastinal mass (may result in SVCO)

- Testicular enlargement

Lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly are common at diagnosis. Hepatomegaly and splenomegaly are seen in upwards of 60% of children at diagnosis. The enlargement itself may be noticed or cause anorexia or discomfort.

Leucostasis

May occur due to large numbers of white cells entering the bloodstream. Organ dysfunction may result due to impairment of flow through small blood vessels. Features include:

- Altered mental state

- Headache

- Breathlessness

- Visual changes

T-cell ALL

T-cell ALL is rarer than the B-cell form. It is said to typically present in adolescent males with lymphadenopathy or a mediastinal mass.

Investigations & diagnosis

Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy is the definitive diagnostic test.

Bloods

The majority of patients will have abnormal haematology labs at diagnosis. Anaemia and thrombocytopenia are common as is leucocytosis. Though the overall WCC may be elevated neutropenia is often seen.

Uric acid and LDH are non-specific markers of tumour burden. Electrolyte derangement may occur and can be multifactorial. Hypercalcaemia may result from the release of a PTH-like hormone or bony involvement.

Coagulation screen and DDIMER are important to evaluate for features of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), a potential complication of ALL.

- FBC

- Renal function

- LFTs

- Clotting screen

- DDIMER

- Bone profile & Mg

- Uric acid

- LDH

- Blood borne virus screen

Imaging

CXR: may demonstrate a mediastinal mass.

CT chest, abdomen and pelvis: assess for lymphadenopathy and organ involvement

CT/MRI head: in patients with symptoms indicative of neurological involvement or to exclude differentials.

Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy

This is the definitive diagnostic test. It allows for staining (Wright or Giemsa) and the review of cell morphology. Immunophenotyping is used to identify the lineage. Samples are sent for cytogenetics and flow cytometry.

Further tests

- Blood smear

- Pleural tap: if a pleural effusion is present a sample should be sent.

- Lumbar puncture: may be organised if there is concern of CNS involvement.

Prognostic factors

Certain factors are associated with a poorer prognosis.

The following are high-risk factors for adult patients:

- Age (worse with advancing age)

- Performance status > 1

- White cell count (> 30 for B-cell ALL, > 100 for T-cell ALL)

- Cytogenetics

- t(9;22) - Philadelphia chromosome

- t(4;11)

- Immunophenotype (pro-B/early and mature-T)

- CNS involvement

Other risk factors are described by the initial treatment response. For those interested click here for more detail.

Management

ALL is a rare condition with complex treatment protocols that differ depending on the patients age and underlying disease type.

Patients should be referred to a specialist haemato-oncology unit for specialist management. Most patients will be enrolled in a clinical trial as part of their treatment.

Treatment aims to halt disease progression and return normal marrow function. Chemotherapy represents the mainstay of treatment with stem cell transplant used in select patients.

Pre-phase and supportive therapy

Patients are transferred to a specialist haemato-oncology unit. It is essential patients are cared for by appropriate medical specialists and nursing staff with access to HDU/ITU if required. Key aspects of management include:

- Pre-phase therapy: patients may be commenced on steroids (at times with other medications), often in conjunction with allopurinol and IV hydration. This pre-phase helps reduce the risk of TLS. Rasburicase may be required depending on the risk of TLS.

- Leucopheresis: not commonly used but may be required to reduce the white cell count, helps to mitigate the risk of TLS.

- Supportive therapy: anaemia and thrombocytopenia may require treatment if severe. Neutropenia is common and G-CSF may be given.

Induction chemotherapy

The aim of induction chemotherapy is to achieve complete remission or ideally complete molecular remission:

- Complete remission (CR): leukaemia not seen in bone marrow, peripheral blood or CSF (less than 5% blasts in bone marrow).

- Molecular complete remission (MolCR): as per CR, minimal residual disease not detectable by sensitive molecular probe.

The selection of chemotherapy is dependent on a multitude of factors including age, Philadelphia chromosome status and the presence of CNS disease. Those with CNS disease require intrathecal chemotherapy and prophylactic therapy may be used in those without to reduce the risk of CNS relapse.

Maintenance therapy

This aims to reduce the risk of recurrence. Regimens normally include daily 6-mercaptopurine and weekly methotrexate though there is considerable variation.

Stem cell transplant

Allogeneic stem-cell transplant may be considered. It reduces the risk of relapse. Myeloablative transplant refers to the use of high-dose chemotherapy followed by stem cell transplant.

Palliative care

The involvement of palliative care should be considered in any patient undergoing treatment without curative intent, or in those with disease symptoms that are difficult to manage.

Complications

Patients (particularly after the commencement of chemotherapy) are at risk of neutropenic sepsis and tumour lysis syndrome.

- Tumour lysis syndrome: significant metabolic disturbances arising from the rapid breakdown of malignant cells, normally after therapy has been initiated. It should be anticipated and when appropriate prophylaxis may be given with close monitoring and HDU/ITU availability if needed.

- Neutropenic sepsis: characterised by fever and neutrophils < 0.5 (or expected to fall below 0.5). A medical emergency requiring early identification and management.

- SVCO: patients may present with features of superior vena cava obstruction (e.g. dyspnea, facial swelling, cough) secondary to a mediastinal mass.

- Chemotherapy side-effects: depends on the therapy and intensity, can be early (e.g. mucositis, nausea and vomiting, hair loss) or late (e.g. cardiomyopathy, secondary malignancies)

Last updated: June 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback